“Of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the greatest number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people, commencing demagogues and ending tyrants.” —Alexander Hamilton

Outline

- The Authoritarian Playbook (Protect Democracy)

- How Autocratization Unfolds (V-Dem Democracy Report 2021 Page 22)

- Six Ways Authoritarians Rig Elections (Cheeseman and Klass)

- Managed System of Entrenched Minority Rule (Christopher R. Browning)

- Outline of How Democracies Die (Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt)

The Authoritarian Playbook

(Protect Democracy)

- Politicizing Independent Institutions

- Spreading Disinformation

- Many politicians lie, but authoritarians propagate and amplify falsehoods deliberately and with abandon and ruthless efficiency. Disinformation is a unique challenge for the United States today, as authoritarian actors have taken advantage of our strong First Amendment tradition and fragmented online information ecosystem.

- Aggrandizing Executive Power and Undermining Checks & Balances

- Quashing Dissent

- Scapegoating Vulnerable Communities

- Corrupting Elections

- Stoking Violence

Link to The Authoritarian Playbook, Overview

Link to The Authoritarian Playbook, Full Report

How Autocratization Unfolds

(V-Dem Democracy Report 2021 Page 22)

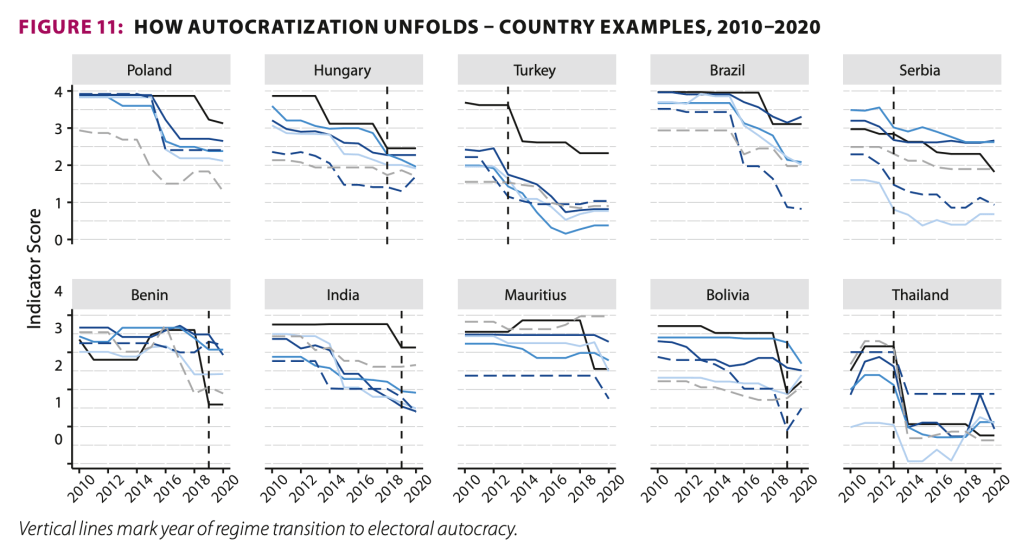

- When V-Dem data on the indicators comprising the LDI are analyzed to decipher how contemporary autocratization unfolds, a striking pattern emerges. The playbook of “wannabe” dictators seems to have been shared widely among leaders in (former) democracies.

- First, seek to restrict and control the media while curbing academia and civil society.

- Then couple these with disrespect for political opponents to feed polarization while using the machinery of the government to spread disinformation.

- Only when you have come far enough on these fronts is it time for an attack on democracy’s core: elections and other formal institutions.

- Figure 11 shows those indicators that tended to deteriorate first and ultimately the most, among the top 10 autocratizing countries. Vertical dashed lines indicate if a democratic breakdown took place, meaning that autocratization has gone so far that the country is downgraded to an electoral autocracy.

Six Ways Authoritarians Rig Elections

(Cheeseman and Klass)

- How to Rig an Election, by Nic Cheeseman and Brian Klaas , Yale University Press, 2018

- Election rigging can be broken down into six subcategories of manipulation.

- The first is gerrymandering, in which leaders distort the size of district boundaries so that their parties have a head start in legislative elections. By these means, opposition parties can end up with fewer seats even if they receive more votes.

- The second is vote buying, which involves the direct purchase of citizens’ support through cash gifts or, as it is often referred to in Africa, ‘something small’. This can be an effective way to secure votes that could not be earned, but it is an expensive strategy and – when the ballot is secret – one that is difficult to enforce. Voters may be able to take bribes from one candidate and then vote for another without consequence.

- Autocrats may also employ a third type of rigging, engaging in repression to prevent other candidates from campaigning, deny them access to the media, and intimidate rival supporters in order to stop them going to the polls.

- If these strategies don’t work, counterfeit democrats have two main options left open to them:

- digitally hacking the election in order to change the debate and, in some cases, to rewrite the result; and

- stuffing the ballot box – adding fake votes or facilitating multiple voting in order to improve a given candidate’s performance.

- To get away with such tactics, they may also need to play the international community, duping donors into legitimizing poor-quality polls. Because the latter three options can easily backfire, the most effective autocrats don’t leave election rigging to the last minute.

Managed System of Entrenched Minority Rule

(Christopher R. Browning)

- How Hitler’s Enablers Undid Democracy in Germany, Christopher R. Browning, Professor of History Emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Atlantic

- The American political system has some built-in vulnerabilities to illiberal, antidemocratic actors—flaws that the Republican Party exploited even before Donald Trump took it over. Since 1992, Republicans have won the popular vote in a presidential election only once. But the U.S. Constitution has provided them with intrinsic advantages in the forms of the Electoral College and the Senate: Both bodies overrepresent parts of the country where Republicans are strong (less-populated states and areas) and underrepresent more Democratic-leaning localities (populous states and urban areas). As a result, the Democrats have to win the popular vote by a disproportionately large margin to prevail in either the Electoral College or the Senate.

- The post-2010 gerrymandering of state legislature and U.S. House redistricting—executed with unprecedented precision through sophisticated data processing—has hugely exacerbated the problem. (Democrats are guilty of the practice too, but Republicans are unrivaled in the ruthlessness they’ve brought to the task.) The only electoral suspense in what should be toss-up states such as North Carolina and Wisconsin is whether Republicans can attain veto-proof supermajorities in state legislatures based on roughly half the popular vote. Supreme Court decisions gutting crucial parts of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 have cleared the way for a host of voter-suppression measures. The purging of electoral officials and the Republican nomination of election deniers for governor and secretary of state in battleground states are even more ominous warnings. This pattern of GOP activity adds up to an effort to rule by executing a specifically American form of legal revolution.

- But the twin humiliations of Trump’s electoral defeat in 2020 and the failure of the insurrection he fomented have raised the stakes. They have cemented the connection between Trump’s obsession with the myth of a stolen election and the long-term project of transforming American democracy into a managed system of entrenched minority rule.

- In the immediate postelection period, Trump and his inner circle plotted to create fake electors, pressured state election officials to “find” the necessary votes to reverse the outcome, and ultimately instigated the January 6 insurrection. More broadly, 147 congressional Republicans voted against certifying Biden’s election, and 17 Republican state attorneys general joined a suit to overturn the election results in four battleground states; the party then rallied together to condemn and withdraw support for Representatives Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger for daring to expose the Big Lie.

- The GOP has now embraced an accelerated strategy of legal revolution to control the outcome of future elections.

Outline of How Democracies Die

(Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt)

Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt are Harvard professors who have spent twenty years studying the breakdown of democracies in Europe and Latin America

- Introduction

- Since the end of the Cold War, most democratic breakdowns have been caused not by generals and soldiers but by elected governments themselves. Some of these leaders dismantle democracy quickly, as Hitler did in the wake of the 1933 Reichstag fire in Germany. More often, though, democracies erode slowly, in barely visible steps.

- How vulnerable is American democracy to this form of backsliding?

- Extremist demagogues emerge from time to time in all societies, even in healthy democracies. The United States has had its share of them, including Henry Ford, Huey Long, Joseph McCarthy, and George Wallace.

- An essential test for democracies is not whether such figures emerge but whether political leaders, and especially political parties, work to prevent them from gaining power in the first place—by keeping them off mainstream party tickets, refusing to endorse or align with them, and when necessary, making common cause with rivals in support of democratic candidates.

- Once a would-be authoritarian makes it to power, democracies face a second critical test: Will the autocratic leader subvert democratic institutions or be constrained by them? Institutions alone are not enough to rein in elected autocrats. Constitutions must be defended—by political parties and organized citizens, but also by democratic norms.

- Democracies work best—and survive longer—where constitutions are reinforced by unwritten democratic norms. Two basic norms have preserved America’s checks and balances in ways we have come to take for granted:

- mutual toleration, or the understanding that competing parties accept one another as legitimate rivals, and

- forbearance, or the idea that politicians should exercise restraint in deploying their institutional prerogatives.

- The erosion of our democratic norms began in the 1980s and 1990s and accelerated in the 2000s. By the time Barack Obama became president, many Republicans, in particular, questioned the legitimacy of their Democratic rivals and had abandoned forbearance for a strategy of winning by any means necessary. Donald Trump may have accelerated this process, but he didn’t cause it. The challenges facing American democracy run deeper. The weakening of our democratic norms is rooted in extreme partisan polarization—one that extends beyond policy differences into an existential conflict over race and culture. America’s efforts to achieve racial equality as our society grows increasingly diverse have fueled an insidious reaction and intensifying polarization.

- Fateful Alliances

- We’ve developed a set of four behavioral warning signs that can help us know an authoritarian when we see one. We should worry when a politician

- 1) rejects, in words or action, the democratic rules of the game,

- 2) denies the legitimacy of opponents,

- 3) tolerates or encourages violence,

- 4) indicates a willingness to curtail the civil liberties of opponents, including the media.

- What kinds of candidates tend to test positive on a litmus test for authoritarianism? Very often, populist outsiders do. Populists are antiestablishment politicians—figures who, claiming to represent the voice of “the people,” wage war on what they depict as a corrupt and conspiratorial elite. Populists tend to deny the legitimacy of established parties, attacking them as undemocratic and even unpatriotic. They tell voters that the existing system is not really a democracy but instead has been hijacked, corrupted, or rigged by the elite. And they promise to bury that elite and return power to “the people.”

- We’ve developed a set of four behavioral warning signs that can help us know an authoritarian when we see one. We should worry when a politician

- Gatekeeping in America

- Gatekeepers in a democracy are the institutions responsible for preventing would-be authoritarians from coming into power.

- Alexander Hamilton worried that a popularly elected presidency could be too easily captured by those who would play on fear and ignorance to win elections and then rule as tyrants.

- “History will teach us,” Hamilton wrote in the Federalist Papers, that “of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the great number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants.”

- For Hamilton and his colleagues, elections required some kind of built-in screening device.

- The device they chose was the Electoral College, made up of locally prominent men in each state who would be responsible for choosing the president. Under this arrangement, Hamilton reasoned, “the office of president will seldom fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.” The Electoral College thus became our original gatekeeper.

- The rise of parties in the early 1800s changed the way our electoral system worked. Instead of electing local notables as delegates to the Electoral College, as the founders had envisioned, each state began to elect party loyalists. Electors became party agents, which meant that the Electoral College surrendered its gatekeeping authority to the parties.

- Political parties thus became the gatekeepers of American democracy.

- The Great Republican Abdication

- In the twenty-three years between 1945 and 1968, under the old convention system, only a single outsider (Dwight Eisenhower) publicly sought the nomination of either party.

- But the primary system had opened up the presidential nomination process more than ever before in American history.

- The post-1972 primary system was especially vulnerable to a particular kind of outsider: individuals with enough fame or money to skip the “invisible primary.” In other words, celebrities.

- Party gatekeepers were shells of what they once were, for two main reasons.

- One was a dramatic increase in the availability of outside money, accelerated (though hardly caused) by the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United ruling.

- The other major factor diminishing the power of traditional gatekeepers was the explosion of alternative media, particularly cable news and social media.

- Subverting Democracy

- Three strategies by which elected authoritarians seek to consolidate power:

- capturing the referees,

- sidelining the key players, and

- rewriting the rules to tilt the playing field against opponents.

- Three strategies by which elected authoritarians seek to consolidate power:

- The Guardrails of Democracy

- All successful democracies rely on informal rules (or norms) that, though not found in the constitution or any laws, are widely known and respected. In the case of American democracy, this has been vital.

- Two norms stand out as fundamental to a functioning democracy: mutual toleration and institutional forbearance.

- Mutual toleration is the idea that as long as our rivals play by constitutional rules, we accept that they have an equal right to exist, compete for power, and govern.

- Institutional forbearance is avoiding actions that, while respecting the letter of the law, violate its spirit.

- The Unwritten Rules of American Politics

- Unwritten rules are everywhere in American politics, ranging from the operations of the Senate and the Electoral College to the format of presidential press conferences.

- By the turn of the twentieth century norms of mutual toleration and institutional forbearance were well-established. Indeed, they became the foundation of our much-admired system of checks and balances.

- In the absence of these norms, this balance becomes harder to sustain. When partisan hatred trumps politicians’ commitment to the spirit of the Constitution, a system of checks and balances risks being subverted in two ways.

- Under divided government, where legislative or judicial institutions are in the hands of the opposition, the risk is constitutional hardball, in which the opposition deploys its institutional prerogatives as far as it can extend them—defunding the government, blocking all presidential judicial appointments, and perhaps even voting to remove the president. In this scenario, legislative and judicial watchdogs become partisan attack dogs.

- Under unified government, where legislative and judicial institutions are in the hands of the president’s party, the risk is not confrontation but abdication. If partisan animosity prevails over mutual toleration, those in control of congress may prioritize defense of the president over the performance of their constitutional duties. In an effort to stave off opposition victory, they may abandon their oversight role, enabling the president to get away with abusive, illegal, and even authoritarian acts.

- U.S. presidents, congressional leaders, and Supreme Court justices enjoy a range of powers that, if deployed without restraint, could undermine the system.

- Consider six of these powers.

- Three are available to the president: executive orders, the presidential pardon, and court packing. Another three lie with the Congress: the filibuster, the Senate’s power of advice and consent, and impeachment.

- The Unraveling

- Behind the unraveling of basic norms of mutual tolerance and forbearance lies a syndrome of intense partisan polarization.

- But the polarization has been asymmetric, moving the Republican Party more sharply to the right than it has moved the Democrats to the left. Ideologically sorted parties don’t necessarily generate the “fear and loathing” that erodes norms of mutual toleration, leading politicians to begin to question the legitimacy of their rivals.

- The social, ethnic, and cultural bases of partisanship have also changed dramatically, giving rise to parties that represent not just different policy approaches but different communities, cultures, and values. We have already mentioned one major driver of this: the civil rights movement. But America’s ethnic diversification was not limited to black enfranchisement. Beginning in the 1960s, the United States experienced a massive wave of immigration, first from Latin America and later from Asia, which has dramatically altered the country’s demographic map. In 1950, nonwhites constituted barely 10 percent of the U.S. population. By 2014, they constituted 38 percent, and the U.S. Census Bureau projects that a majority of the population will be nonwhite by 2044. Together with black enfranchisement, immigration has transformed American political parties.

- The Republican Party has also become the party of evangelical Christians. Evangelicals entered politics en masse in the late 1970s, motivated, in large part, by the Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion. Beginning with Ronald Reagan in 1980, the GOP embraced the Christian Right and adopted increasingly pro-evangelical positions, including opposition to abortion, support for school prayer, and, later, opposition to gay marriage.

- Democratic voters, in turn, grew increasingly secular.

- In other words, the two parties are now divided over race and religion—two deeply polarizing issues that tend to generate greater intolerance and hostility than traditional policy issues such as taxes and government spending.

- But why was most of the norm breaking being done by the Republican Party?

- It is not only media and outside interests that have pushed the Republican Party toward extremism. Social and cultural changes have also played a major role. Unlike the Democratic Party, which has grown increasingly diverse in recent decades, the GOP has remained culturally homogeneous. This is significant because the party’s core white Protestant voters are not just any constituency—for nearly two centuries, they comprised the majority of the U.S. electorate and were politically, economically, and culturally dominant in American society. Now, again, white Protestants are a minority of the electorate—and declining. And they have hunkered down in the Republican Party.

- Trump Against the Guardrails

- In Chapter 4, we presented three strategies by which elected authoritarians seek to consolidate power: capturing the referees, sidelining the key players, and rewriting the rules to tilt the playing field against opponents. Trump and other Republicans attempted all three of these strategies.

- President Trump demonstrated striking hostility toward the referees—law enforcement, intelligence, ethics agencies, and the courts.

- The Trump administration also mounted efforts to sideline key players in the political system. President Trump’s rhetorical attacks on critics in the media are an example. His repeated accusations that outlets such as the New York Times and CNN were dispensing “fake news” and conspiring against him look familiar to any student of authoritarianism.

- Republican state legislatures tried to tilt the playing field by enacting strict voter ID laws.

- Perhaps the most antidemocratic initiative yet undertaken by the Trump administration is the creation of the Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity, chaired by Vice President Mike Pence but run by Vice Chair Kris Kobach.

- Perhaps President Trump’s most notorious norm-breaking behavior has been lying.

- In Chapter 4, we presented three strategies by which elected authoritarians seek to consolidate power: capturing the referees, sidelining the key players, and rewriting the rules to tilt the playing field against opponents. Trump and other Republicans attempted all three of these strategies.

- Saving Democracy

- America’s democratic norms, at their core, have always been sound. But for much of our history, they were accompanied—indeed, sustained—by racial exclusion. Now those norms must be made to work in an age of racial equality and unprecedented ethnic diversity. Few societies in history have managed to be both multiracial and genuinely democratic. That is our challenge. It is also our opportunity. If we meet it, America will truly be exceptional.