Contents

- Skepticism

- Brain-in-a-Vat Thought Experiment

- Brain-in-a-Vat Argument for Skepticism about the External World

- Responses to the Argument

Skepticism

- There are two kinds of Skepticism.

- Practical Skepticism is the disposition to believe based only on the evidence and arguments.

- Philosophic Skepticism is the doctrine that there’s no rational basis for believing various classes of propositions, for example:

- propositions about the external world: that there are tables, trees, cars, houses, and the myriad other things that occupy space and time

- propositions about other minds: that other people, like oneself, are conscious beings having thoughts, sensations, feelings, emotions, and beliefs.

- The thesis that there’s no rational basis for believing a proposition P logically implies that

- No one is justified in believing P

- It’s irrational to believe P

- No one knows that P.

- View Practical vs Philosophic Skepticism

- The Brain-in-a-Vat Thought Experiment is the basis for arguing that it’s not rational to believe propositions about the external world.

Brain-in-a-Vat Thought Experiment

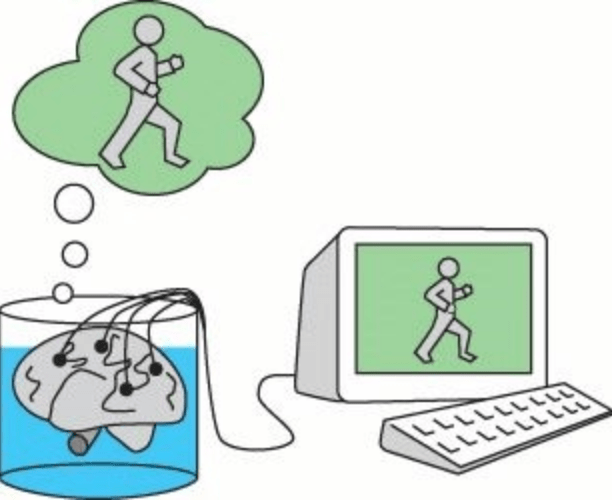

- You have undergone an operation in which your brain is removed and stored in a vat of nutrients that keeps it alive. The nerve endings of your brain are connected to a supercomputer that runs a program sending electrical impulses that stimulate the brain in the same way that brains are stimulated when perceiving external objects. So your conscious experiences are indistinguishable from the experiences you had before the operation. But you no longer have a body or see real objects or converse with other people, though it seems you do.

So here’s what’s going on when you see someone walking

You can thus have the experience of seeing a tomato without actually seeing a tomato

Brain-in-a-Vat Argument for Skepticism about the External World

- Premise 1:

- I currently have the experience of seeing and sensing my hand.

- Premise 2:

- Consider two hypotheses:

- I see and sense my hand

- I don’t see and sense my hand because, being a brain-in-vat, I have no hands. However, sometimes I have the experience of seeing and sensing my hand, as I do now.

- I have no basis for believing that either of these hypotheses is more likely than the other.

- That’s because I have no way of determining whether I’m a normal person or a brain-in-vat.

- Consider two hypotheses:

- Premise 3:

- If there’s no basis for believing that one of two competing hypotheses is more likely than the other, it’s not rational to believe either.

- For example, if the evidence favors neither of two hypotheses:

- that the plane crashed because of a mechanical failure

- that the plane crashed because of pilot error

- it’s not rational to believe either.

- For example, if the evidence favors neither of two hypotheses:

- If there’s no basis for believing that one of two competing hypotheses is more likely than the other, it’s not rational to believe either.

- Conclusion:

- It’s not rational to believe I see and sense my hand

Responses to the Argument

- Like everyone else, philosophers believe that of course they see and sense various parts of their body.

- The problem is articulating what’s wrong with the brain-in-a-vat argument

Appeal to Common Sense

- GE Moore

- “This, after all, you know, really is a finger: there is no doubt about it: I know it, and you all know it. And I think we may safely challenge any philosopher to bring forward any argument in favor either of the proposition that we do not know it, or of the proposition that it is not true, which does not at some point, rest upon some premiss which is, beyond comparison, less certain than is the proposition which it is designed to attack.”

Natural World Theory is Simpler

- Bertrand Russell argued that it rational to believe in an external world because it’s the simplest, most natural explanation of our sense data.

- Bertrand Russell: Problems of Philosophy, Page 22-23

- There is no logical impossibility in the supposition that the whole of life is a dream, in which we ourselves create all the objects that come before us. But although this is not logically impossible, there is no reason whatever to suppose that it is true; and it is, in fact, a less simple hypothesis, viewed as a means of accounting for the facts of our own life, than the common-sense hypothesis that there really are objects independent of us, whose action on us causes our sensations.

- The way in which simplicity comes in from supposing that there really are physical objects is easily seen. If the cat appears at one moment in one part of the room, and at another in another part, it is natural to suppose that it has moved from the one to the other, passing over a series of intermediate positions. But if it is merely a set of sense-data, it cannot have ever been in any place where I did not see it; thus we shall have to suppose that it did not exist at all while I was not looking, but suddenly sprang into being in a new place. If the cat exists whether I see it or not, we can understand from our own experience how it gets hungry between one meal and the next; but if it does not exist when I am not seeing it, it seems odd that appetite should grow during non-existence as fast as during existence. And if the cat consists only of sense-data, it cannot be hungry, since no hunger but my own can be a sense-datum to me. Thus the behaviour of the sense-data which represent the cat to me, though it seems quite natural when regarded as an expression of hunger, becomes utterly inexplicable when regarded as mere movements and changes of patches of colour, which are as incapable of hunger as a triangle is of playing football.

Making a Virtue of Necessity

- Normally, when a person concludes there’s no rational basis for a belief, they stop believing, e.g. the belief that Iraq had WMDs.

- But that’s not what happens when a person, convinced by the Brain-in-a-Vat argument, concludes that belief in the external world is irrational. Skeptics continue believing there’s an external world because, as David Hume pointed out, “nature is always too strong for principle.”

- Thomas Reid, a contemporary of Hume’s, used the inability to give up the belief in an external world as an argument for its rationality.

- “Methinks, therefore, it were better to make a virtue of necessity; and, since we cannot get rid of the vulgar notion and belief of an external world, to reconcile our reason to it as well as we can; for, if Reason should stomach and fret ever so much at this yoke, she cannot throw it off; if she will not be the servant of Common Sense, she must be her slave.”

- Reid’s idea was that belief in the common-sense worldview of physical objects is rational because no rational argument can dislodge it. What’s rational to believe must be believable.

Quotes

- Charles Sanders Peirce

- “Some philosophers have imagined that to start an inquiry it was only necessary to utter a question whether orally or by setting it down upon paper, and have even recommended us to begin our studies with questioning everything! But the mere putting of a proposition into the interrogative form does not stimulate the mind to any struggle after belief. There must be a real and living doubt, and without this all discussion is idle.”

- Otto Neurath

- “We are like sailors who have to rebuild their ship on the open sea, without ever being able to dismantle it in dry-dock and reconstruct it from its best components.”

- Thomas Reid

- “All reasoning must be from first principles; and for first principles no other reason can be given but this, that, by the constitution of our nature, we are under a necessity of assenting to them.”

- Willard Van Orman Quine

- We adopt “the fundamental conceptual scheme of science and common sense.”

- David Hume:

- “But a Pyrrhonian cannot expect, that his philosophy will have any constant influence on the mind: or if it had, that its influence would be beneficial to society. On the contrary, he must acknowledge, if he will acknowledge anything, that all human life must perish, were his principles universally and steadily to prevail. All discourse, all action would immediately cease; and men remain in a total lethargy, till the necessities of nature, unsatisfied, put an end to their miserable existence. It is true; so fatal an event is very little to be dreaded. Nature is always too strong for principle.”