The broadly logical (metaphysical) modalities are fundamental to logic and philosophy

Contents

- Logical Modalities

- Truth Table Definitions of Relational Modalities

- Possible Worlds

- Modalities Defined in Terms of Logical Necessity

- Uses of Logical Modalities in Philosophy

- Necessary Truth and Knowability a Priori

- Addendum

Logical Modalities

- The broadly logical (metaphysical) modalities are fundamental to logic and philosophy in general. They include the modal properties of possibility, necessity, impossibility, and contingency and the modal relations of entailment, incompatibility, equivalence, contradictory, and subcontrary.

Necessary and Contingent Truths

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz introduced calculus into mathematics, kinetic energy into physics, and the distinction between necessary and contingent truths into philosophy, what he called truths of reason and truths of fact.

- From the Monadology (1714) Part II 33

- “There are two kinds of truths, those of reasoning and those of fact. Truths of reasoning are necessary and their opposite is impossible: truths of fact are contingent and their opposite is possible. When a truth is necessary, its reason can be found by analysis, resolving it into more simple ideas and truths, until we come to those which are primary.”

- Truths of reason, Leibniz said, are grounded on the principle of “contradiction, in virtue of which we judge false that which involves a contradiction, and true that which is opposed or contradictory to the false.”

- From the Monadology (1714) Part II 33

- A proposition is logically necessary (or logically true) if its negation implies a contradiction.

- Necessary truths include:

- A proposition is contingently true if it’s true and not logically necessary.

- Examples:

- The sun will rise tomorrow.

- Some molecules have three atoms.

- Harper Lee wrote To Kill a Mockingbird.

- Nothing with mass travels faster than the speed of light.

- Logical modalities are distinct from physical and epistemic modalities.

- A state-of-affairs is physically impossible if it’s incompatible with the laws of a nature. Thus, it’s physically impossible that something move faster than the speed of light. But superliminal speed is not logically impossible since the idea of something traveling faster than light is not impossible in and of itself.

- A state-of-affairs is epistemically impossible if it’s incompatible with what is known (or what is certain). Thus it’s (epistemically) impossible that that are no human beings. Which is to say that it’s certain human beings exist. But the non-existence of human beings is logically possible, since the idea is not a contradiction in terms.

Logical Possibility and Impossibility

- A proposition is logically impossible if it’s necessarily false; and logically possible otherwise,

- Examples of logical impossibilities:

- Some people are taller than themselves,

- 2 + 2 = 22

- An angle can be trisected with only a straightedge and a compass.

Logical Entailment (Logical Consequence)

- A set S of propositions logically entails a proposition Q (or Q is a logical consequence of S) if it’s logically impossible that the propositions of S are all true and Q false.

- Thus, the propositions that only natural-born citizens are eligible to be president and McCormick is not a natural-born citizen logically entail that McCormick is not eligible to be president.

- Deductive validity is logical entailment:

- The argument P1, P2, …, Pn therefore Q is valid just in case P1, P2, …, Pn logically entail Q.

- Entailment is useful in determining relative logical strength, for example:

- It is certain that Q logically entails it is beyond a reasonable doubt that Q, but not vice versa.

- It is beyond a reasonable doubt that Q logically entails it is very likely that Q, but not vice versa.

- Thus, in order of logical strength:

- It is certain that Q

- it is beyond a reasonable doubt that Q

- it is very likely that Q

Logical Equivalence and Contradictories

- Propositions P and Q are logically equivalent just in case each entails the other, which is to say that P and Q necessarily have the same truth-value, either both true or both false.

- For example,

- Not all swans are white is logically equivalent to some swans are not white.

- It is probable that P is logically equivalent to it’s likely that P.

- The opposite of equivalence is contradictory pairs of propositions.

- P and Q are contradictory if it’s logically impossible that P and Q are both true and it’s logically impossible that they are both false, which is to say that they necessarily have opposite truth-values.

- For example, McCormick is at least six feet tall and McCormick is less than six feet tall are contradictory

- P and Q are contradictory if it’s logically impossible that P and Q are both true and it’s logically impossible that they are both false, which is to say that they necessarily have opposite truth-values.

Compatibility, Incompatibility, and Subcontraries

- Two propositions are logically incompatible just in case it’s logically impossible that both are true; and they are logically compatible otherwise.

- Thus, McCormick is over six feet tall is logically incompatible with McCormick is under five feet tall and compatible with McCormick is seven feet tall.

- Two propositions are subcontraries if it’s logically impossible that both are false.

- For example, McCormick is at least 5 feet tall and McCormick is less an 6 feet tall are subcontraries.

- The traditional problem of free will and determinism presupposes that free will and determinism are logically incompatible. One proposed solution has been to claim that there is no problem by arguing that free will and determinism are compatible.

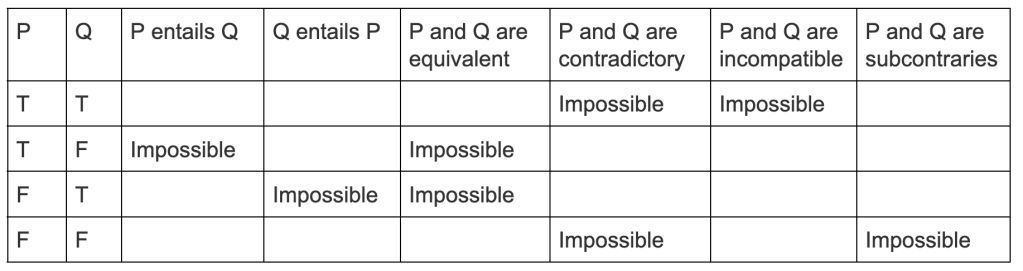

Truth Table Definitions of Relational Modalities

- You can read off the table that:

- Equivalence is mutual entailment

- Superimposing the Impossible rows of “P entails Q” onto the rows of “Q entails P” yields the rows of “P and Q are equivalent.”

- Two propositions are contradictories if and only if they are both incompatible and subcontraries.

- Equivalence and contradictories are opposites.

- The rows for “P and Q are equivalent” and “P and Q are contradictories” are opposite (one blank, the other Impossible).

- Equivalence is mutual entailment

Possible Worlds

- Possible worlds afford a way of reasoning about modalities.

- A possible world, intuitively, is a complete and logically possible way everything could have been.

- Specifically, a possible world is a set of propositions such that

- the set is complete in the sense that, for any proposition, either it or its negation belongs to the set;

- it’s logically possible that all propositions of the set are true.

- A proposition is true in a possible world if it belongs to that world’s set of propositions.

- The actual world is the possible world whose propositions are all true.

- Thus:

- A proposition is logically necesssary if and only if it’s true in all possible worlds.

- A proposition is logically impossible if and only if it’s false in all possible worlds.

- A proposition is contingently true if and only if it’s true in the actual world but false in some possible world.

- Proposition P logically entails Q if and only if Q is true in every possible world in which P is true.

- Propositions P and Q are logically equivalent if and only if P and Q are true in exactly the same possible worlds.

Modalities Defined in Terms of Logical Necessity

Primitive Concepts

- It is logically necessary that P

- Alternatively:

- it is broadly logically necessary that P

- it is logically true that P

- it is metaphysically necessary that P

- Modal Logic

- ⃞P = it is logically necessary that P

- Possible Worlds

- It is logically necessary that P if and only if P is true in all possible worlds

- Alternatively:

- The tilde ~ means it is false that.

- The ampersand & means and.

- The arrow → means if … then —,

Definitions

- It is logically possible that P ≣ it is not logically necessary that P is false

- Modal Logic

- ♢P = ~⃞~P

- Possible Worlds

- It is logically possible that P if and only if P is true in some possible world

- Modal Logic

- It is logically impossible that P ≣ it is logically necessary that P is false

- Modal Logic

- ~♢P = ⃞~P

- Possible Worlds

- It is logically impossible that P if and only P is false in all possible worlds

- Modal Logic

- It is contingently true that P ≣ P is true and it’s logically possible that P is false

- Modal Logic

- P is contingently true = P & ♢~P

- Possible Worlds

- P is contingently true if and only if P is true in the actual world and false in some possible world.

- Modal Logic

- It is contingently false that P ≣ P is false and it’s logically possible that P is true

- Modal Logic

- P is contingently false = ~P & ♢P

- Possible Worlds

- P is contingently false if and only if P is false in the actual world and true in some possible world.

- Modal Logic

- It is contingent that P ≣ it’s logically possible that P is true and logically possible that P is false

- Alternatively, P is either contingently true or contingently false.

- Modal Logic

- P is contingent = ♢P & ♢~P

- Possible Worlds

- It is contingent that P if and only if P is true in some possible world and P is false in some possible world.

- P logically entails Q (or Q is a logical consequence of P) ≣ it is logically necessary that if P then Q

- Alternatively, it is logically impossible that P is true and Q false

- Modal Logic

- P entails Q = ⃞(P→Q) = ~♢(P&~Q)

- Possible Worlds

- P logically entails Q if and only if Q is true in every possible world in which P is true

- Alternatively, P logically entails Q if and only if there is no possible world in which P is true and Q false

- P logically entails Q if and only if Q is true in every possible world in which P is true

- P and Q are logically equivalent ≣ P logically entails Q and Q logically entails P

- Alternatively, P and Q necessarily have the same truth-value (either both true or both false).

- Alternatively, it’s logically impossible that P and Q have different true values

- Modal Logic

- P and Q are logically equivalent = ⃞(P→Q) & ⃞(Q→P)

- Possible Worlds

- P and Q are logically equivalent if and only if P and Q are true in the very same possible worlds

- P and Q are logically incompatible ≣ it’s logically impossible that P and Q are both true

- Modal Logic

- P and Q are logically incompatible = ~♢(P&Q)

- Possible Worlds

- P and Q are logically incompatible if and only if there is no possible world in which P and Q are both true

- Modal Logic

- P and Q are contradictory ≣ it’s logically impossible that P and Q are both true and it’s logically impossible that P and Q are both false.

- Alternatively, P and Q necessarily have different truth values, one true and the other false

- Alternatively, each proposition logically entails that the other is false.

- Modal Logic

- P and Q are contradictory = ~♢(P&Q) & ~♢(~P&~Q) = ⃞(P→~Q) & ⃞(Q→~P)

- Possible Worlds

- P and Q are contradictory if and only if there is no possible world in which P and Q have the same truth value.

- P and Q are subcontraries ≣ it’s logically impossible that P and Q are both false.

- Modal Logic

- P and Q are subcontraries = ~♢(~P&~Q)

- Possible Worlds

- P and Q are subcontraries if and only if there is no possible world in which P and Q are both false

- Modal Logic

Uses of Logical Modalities in Philosophy

- Definition of deductive validity

- An argument is valid just in case it’s logically impossible that the premises are all true and the conclusion false.

- Counterexamples

- Philosophic theses are typically set forth as necessarily true, for example the following thesis about moral responsibility:

- A person is morally responsible for something they’ve done only if they could have done otherwise.

- A counterexample is a logically possible scenario that refutes the thesis. In this case:

- Suppose a lifeguard, who got the job by lying about his ability to swim, isn’t able to save a swimmer in trouble. The lifeguard, it would seem, is morally responsible for the swimmer’s although he couldn’t have done otherwise.

- Philosophic theses are typically set forth as necessarily true, for example the following thesis about moral responsibility:

- Thought-Experiments

- A thought-experiment is a hypothetical scenario, assumed logically possible, set forth as a puzzlement or a basis for argument.

- View Thought-Experiments

- Conceptual Analysis

- Conceptual analysis is the analysis of a concept into its conceptual components, for example, the analysis of knowledge as justified true belief:

- A person knows that P if and only if

- the person believes that P

- it’s true that P

- the person is rationally justified in believing that P.

- The analysis is put forth as logically necessary, that is, that “S knows P” and “S justifiably and correctly believes P” are logically equivalent.

- A person knows that P if and only if

- Conceptual analysis is the analysis of a concept into its conceptual components, for example, the analysis of knowledge as justified true belief:

- Family Connections

- Light can be thrown on a family of words and phrases by setting forth their logical interconnections, for example:

- “It is certain that P” logically entails “it is beyond a reasonable doubt that P,” but not the reverse;

- “It is beyond a reasonable doubt that P” logically entails “there is a preponderance of evidence that P,” but not the reverse.

- Light can be thrown on a family of words and phrases by setting forth their logical interconnections, for example:

Necessary Truth and Knowability a Priori

Knowability a Priori and Knowability Only A Posteriori

- A proposition is knowable a priori if it is knowable independent of (“prior to”) experience, i.e. if it can be known without being based on empirical evidence (which includes the evidence of perception, testimony, memory, and introspection).

- The truth of such propositions is either directly evident or can be derived from from directly-evident truths using deductive logic.

- That all squares are rectangles is directly evident and is thus known a priori.

- That the sum of two odd integers is (always) even can be derived from directly evident truths using deductive logic and is thus known a priori.

- View Quick Proof

- A proposition is knowable only a posteriori if it is knowable only from (“after”) experience, i.e. if it can be known based only on empirical evidence (which includes the evidence of perception, testimony, memory, and introspection).. For example,

- I have a headache

- I saw a Shelby Cobra yesterday

- Black swans exists

- Nothing can travel faster than light.

- Knowability a priori and knowability only a posteriori are conceptually distinct from necessary truth and contingent truth. The first pair are epistemic concepts, relating to knowledge. The second pair are metaphysical, concerning propositions.

- Since Hume, many philosophers assumed that the pairs of concepts coincide, that is:

- A proposition is knowable a priori if and only if it is necessarily true.

- A proposition is knowable only a posteriori if and only if it is contingently true.

- It turns out they were wrong, that is:

- Some necessary truths are knowable only a posteriori.

- Some contingent truths are knowable a priori.

Kripke and Rigid Designators

Necessary Truths Knowable Only a Posteriori

- Some necessary truths are knowable only a posteriori. The reason has to do with names and how they refer to the objects they name.

- The ancient Greeks named the heavenly body that appears near the sun in the morning “Phosphorus.” And they named the heavenly body that appears near the sun in the evening “Hesperus.”

- It was discovered later that both bodies were the planet Venus. It was thus learned that

- Hesperus = Phosphorus

- The identity of Hesperus and Phosphorus is therefore known a posteriori.

- The proposition Hesperus = Phosphorus would seem contingently true. Here’s the argument:

- Names are defined in terms of definite descriptions. Thus,

- “Phosphorus” means the heavenly body that appears near the sun in the morning.

- “Hesperus” means the heavenly body that appears near the sun in the evening.

- Therefore Hesperus = Phosphorus means:

- The heavenly body that appears near the sun in the morning = the heavenly body that appears near the sun in the evening.

- That proposition is contingently true.

- Therefore Hesperus = Phosphorus is contingently true.

- Names are defined in terms of definite descriptions. Thus,

- But in Naming and Necessity (1980), Saul Kripke presents a compelling argument that Hesperus = Phosphorus is necessarily true:

- Names are rigid designators

- A rigid designator designates the same object in all possible worlds in which that object exists and never designates anything else. (stanford.edu/entries/rigid-designators/)

- So names attach necessarily to their objects, sticking to them through possible worlds.

- Therefore,

- “Phosphorus” rigidly designates Phosphorus.

- “Hesperus” rigidly designates Hesperus.

- Since Hesperus = Phosphorus, “Phosphorus” and “Hesperus” rigidly designate the same object

- Therefore “Phosphorus” and “Hesperus” designate the same object in all possible worlds where they exist.

- Hence, it’s necessarily true that Hesperus = Phosphorus.

- Names are rigid designators

- Argument #1 supporting Kripke’s view:

- Suppose Venus changes orbit so it no longer appears near the sun in the morning. According to the definite description theory of names, Hesperus has ceased to exist. Per Kripke’s rigid designator theory, Hesperus has simply changed orbit.

- Argument #2 supporting Kripke’s view:

- If Hesperus = Phosphorus is contingently true, there’s a possible world in which Hesperus is not Phosphorus. Perhaps in that world Hesperus = Mercury. Then Hesperus could have been Mercury. But a thing could not have been a different thing. (I could not have been my brother.). “Hesperus” could have named a different object. But Hesperus could not have been a different thing.

- Rigid designators include not only names but also nouns that refer to natural kinds such as water, heat, and gold. Thus the following, like “Hesperus = Phosphorus,” are necessarily true but knowable only a posteriori:

- Water is H2O

- Gold has atomic number 79.

Contingent Truths Knowable a Priori

- It also seems that some contingent truths are knowable a priori.

- Here’s an updated version of one of Kripke’s examples:

- A meter is defined as the length of the path traveled by light in a vacuum during a time interval of 1/299,792,458 of a second. “One meter” thus rigidly designates that length. Consider the statement:

- The length of the path traveled by light in a vacuum during a time interval of 1/299,792,458 of a second is one meter.

- We know a priori that the statement is true, based on the definition of “meter.” But the statement is only contingently true, since it’s false in a possible world where the speed of light is not 299,792,458 meters per second. For example, in a possible world where the speed of light is half of its actual speed (i.e. 149,896,229 m/s), the length of the path traveled by light in a vacuum during 1/299,792,458 of a second is half a meter.

- A meter is defined as the length of the path traveled by light in a vacuum during a time interval of 1/299,792,458 of a second. “One meter” thus rigidly designates that length. Consider the statement:

Addendum

Proof that the sum of two odd integers is even

- An integer is even if it’s two times some positive integer.

- An integer is odd if it’s two times some positive integer + 1.

- Let x and y be two odd integers.

- Then, x = 2a + 1, for some integer a.

- And y = 2b + 1, for some integer b.

- So x + y = 2a + 1 + 2b + 1.

- Thus, x + y = 2a + 2b + 2.

- And so x + y = 2(a + b + 1).

- Thus x + y = two times some integer (a + b + 1) and is therefore even.

- The proposition that sum of two odd integers is even is logically necessary because it’s follows from the definitions of even and odd. See the proof. ↩︎

- It’s logically necessary that water is H2O because “water” and “H2O” are rigid designators. View Naming and Necessity. ↩︎