Back to Democracy

Outline

- Electoral College

- Why the Framers chose the Electoral College

- Electoral Systems for Electing the President

- Main Argument Against the Electoral College

- Standard Arguments

- National Popular Vote (NPV)

- Rerun of 2000 Presidential Election

- Rerun of 2016 Presidential Election

Electoral College

- The President and Vice President are elected by the 538 electors of the Electoral College rather than directly by the people. Each elector has one vote.

- Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution:

- Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress

- Thus,

- a state gets n electors, n being the total number of its Senators and Representatives

- a state’s legislature can choose its electors any way it wants.

- The 23rd Amendment (1961) allocates to the District of Columbia the number of electors equal to the number of the least-populated state, meaning 3 electors.

- The total number of electors is therefore 100 + 435 + 3 = 538

- To win, a candidate needs a majority of the electoral votes, 270.

- The states gradually transitioned from their legislatures choosing electors to election of electors by popular vote. (Wikipedia):

- Initially, state legislatures chose the electors in most states.

- By 1824, there were six states whose legislatures selected electors.

- By 1832, only South Carolina selected electors by legislature vote.

- Since 1864, electors in every state have been chosen based on the popular vote.

- The winner of a state’s popular vote gets all its electoral votes, with two exceptions.

- Maine and Nebraska allocate one electoral vote to the winner of each House district and two electoral votes to the statewide winner.

- Four presidents (so far) have been elected though losing the popular vote.

- Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876

- Benjamin Harrison in 1888

- George W. Bush in 2000

- Donald Trump in 2016.

- At the Constitutional Convention, delegates considered three ways of selecting the President:

- Congress would choose the president, like a parliament electing a prime minister.

- The people would choose the president, by popular vote.

- A counsel of electors appointed by the states would choose the president, like the College of Cardinals choosing the pope.

- Having rejected the first two options, the Electoral College was the only option left.

Why the Framers chose the Electoral College

- Tyranny of the Minority: Why American Democracy Reached the Breaking Point, by Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky 2023

- The question of how to select the new republic’s president was the “most difficult” the framers confronted during the convention, according to the Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson. At the time, most independent nations were monarchies; the framers had few good models for the new republic, and most of them were ancient. They had to design a non-monarchical executive “from scratch.” How to choose their chief magistrate?

- The initial draft proposal, backed by Madison and embedded in the Virginia Plan, called for Congress to choose the president—a system not unlike the parliamentary model of democracy that would later emerge in Europe during the nineteenth century. Parliamentarism eventually became a common type of democracy, but at the time many delegates feared the president would be overly beholden to Congress, so the system was rejected.

- James Wilson argued for popular election of the president. This is how all other presidential and semi-presidential democracies—from Argentina to France to South Korea—elect their executives today. But at the time, there were no presidential democracies, and in Philadelphia in 1787 most delegates were still too distrustful of the “people” to accept direct elections, and the proposal was twice voted down by the convention. Southern delegates were particularly opposed to direct presidential elections. As Madison recognized, the South’s heavy suffrage restrictions, including the disenfranchisement of the enslaved population, left it with many fewer eligible voters than the North. Because the slaveholding South seemed certain to lose any national popular vote, the constitutional scholar Akhil Reed Amar writes, direct elections were a “dealbreaker” for them.

- Once again, the convention was deadlocked, unable to agree on a method of selecting the president. The delegates debated the issue for twenty-one days and held thirty separate votes—more than for any other issue. Every proposed alternative was voted down.

- Finally, as the convention was drawing to a close in late August, the matter was handed off to its Committee on Unfinished Parts. They proposed a model that had been used to “elect” monarchs and emperors under the Holy Roman Empire, a confederation of more than a thousand semi-sovereign territories and lordships in central Europe. When the emperor died, local princes and archbishops gathered in a Council of Electors (Kurfürstenrat), usually in Frankfurt, Germany, to vote on a new emperor. This is similar to how popes have been chosen since the Middle Ages. Even today, with the passing of a pope, the Sacred College of Cardinals convenes in Rome to “elect a successor.” America’s constitutional framers deployed a variant of this “medieval relic” in a non-monarchical setting, which came to be known as the Electoral College.

- The historian Alexander Keyssar calls the Electoral College a “consensus second choice,” adopted by a convention that could not agree on an alternative. Madison personally viewed direct elections as the “fittest” method to choose a president, but he ultimately recognized that the Electoral College generated the “fewest objections,” largely because it provided additional advantages to both the southern slave states and the small states. The number of electoral votes assigned to each state would be equal to that state’s House delegation plus its two senators. This arrangement satisfied the southern states because House representatives would be elected under the three-fifths clause, and it satisfied the small states because the Senate was based on equal state representation. In this way, both sets of states had a greater say in the selection of the president than they would have had in a system of direct popular election.

- The Electoral College never did what it was designed to do. Hamilton expected it to be composed of highly qualified notables, or prominent elites, chosen by state legislatures, who would act independently. This proved illusory. The Electoral College immediately became an arena of party competition. As early as 1796, electors acted as strictly partisan representatives.

- The question of how to select the new republic’s president was the “most difficult” the framers confronted during the convention, according to the Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson. At the time, most independent nations were monarchies; the framers had few good models for the new republic, and most of them were ancient. They had to design a non-monarchical executive “from scratch.” How to choose their chief magistrate?

- Factcheck

- Most of the nation’s Framers were actually rather afraid of democracy, and wanted an extra layer beyond the direct election of the president. As Alexander Hamilton writes in “The Federalist Papers,” the Constitution is designed to ensure “that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.”

- Concise Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History

- Many of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 initially were convinced that the president should be chosen by majority vote of Congress or the state legislatures. Both these options steadily lost popularity as it became clear the Convention did not want to make the presidency beholden to the legislature or to the states.

- However, many delegates also found distasteful the most viable alternative— direct election by the populace— due to fears that the public would not be able to make an intelligent choice and hence would simply splinter among various regional favorite-son candidates.

- How Democracies Die by Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky

- Gatekeepers in a democracy are the institutions responsible for preventing would-be authoritarians from coming into power.

- In designing the Constitution the founders were concerned with gatekeeping. They wanted an elected president, reflecting the will of the people. But they did not fully trust the people’s ability to judge candidates’ fitness for office.

- “History will teach us,” Hamilton wrote in the Federalist Papers, that “of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the great number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants.” For Hamilton and his colleagues, elections required some kind of built-in screening device.

- The device they chose was the Electoral College, made up of locally prominent men in each state who would be responsible for choosing the president. Under this arrangement, Hamilton reasoned, “the office of president will seldom fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.” The Electoral College thus became our original gatekeeper.

- The rise of political parties in the early 1800s changed the way our electoral system worked. (The Constitution does not mention political parties.) Instead of electing local notables as delegates to the Electoral College, as the founders had envisioned, each state began to elect party loyalists. Electors became party agents, which meant that the Electoral College surrendered its gatekeeping authority to the parties.

Electoral Systems for Electing the President

- Current Electoral College

- A state’s electoral votes are awarded winner-take-all, except for Maine and Nebraska. So:

- 529 electoral votes are winner-take-all in 48 states

- 4 electoral votes in Maine are split:

- 2 for winners of its two congressional districts

- 2 for statewide winner

- 5 electoral votes in Nebraska are split:

- 3 for winners of its three congressional districts

2 for statewide winner

- 3 for winners of its three congressional districts

- A state’s electoral votes are awarded winner-take-all, except for Maine and Nebraska. So:

- Electoral College, Maine-Nebraska System

- A state’s electoral votes are awarded:

- n electoral votes to the winners of its congressional districts

- 2 electoral votes to the statewide winner.

- Based on the analysis set forth in Chapter Four of Every Vote Equal: A State-Based Plan for Electing the President by National Popular Vote, the authors conclude that, for the 2000 presidential election (in which Gore received more votes but lost the election), the Maine-Nebraska system would have resulted in Bush beating Gore 288 electoral votes to 250.

- In What If All States Split Their Electoral Votes?, Taegan Goddard argues that had the Maine-Nebraska system been used in the 2012 election, Romney would have defeated Obama 277 electoral votes to 260.

- A state’s electoral votes are awarded:

- Electoral College, Whole-Number Proportional

- A state’s electoral votes are awarded to candidates in proportion to their popular vote in the state, rounded to the nearest whole number

- Under the Whole-Number Proportional system, the 2000 presidential election (in which Gore received more votes but lost the election), the result would have been a 269-269 electoral vote tie.

- View Rerun of 2000 Presidential Election below.

- Electoral College, Fractional Proportional

- A state’s electoral votes are awarded to candidates in proportion to their popular vote in the state as decimal fractions, e.g. 16.201 rather than 16.

- Under the Fractional Proportional system, the 2000 presidential election (in which Gore received more votes but lost the election), Bush still would have beaten Gore, this time 269.232 electoral votes to 268.768.

- View Rerun of 2000 Presidential Election below.

- Electoral College, National Popular Vote (NPV)

- State legislatures that enact the NPV agree that their state’s electoral votes would be cast for the winner of the national popular vote—even if that person was not the winner of the state’s popular vote. Language in the bill stipulates that it would not take effect until the NPV was passed by states possessing enough electoral votes to determine the winner of the presidential election, 270. As of April, 2023, NPV has been enacted into law by 15 states and DC with 195 electoral votes and needs an additional 75 electoral votes to go into effect.

- States: CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, HI, IL, MA, MD, NJ, NM, NY, RI, VA, VT, WA

- Direct Popular Vote, Replacing Electoral College

- Variants

- Plurality: Candidate with the most votes wins.

- Majority: Candidate needs a majority to win, either by:

- Runoff election

- Ranked Choice Voting.

- Variants

Main Argument Against the Electoral College

- In elections for mayors, governors, and presidents of organizations, people vote, the votes are tallied, and the candidate with the most votes wins. The method is simple, easily understood, widely used, and satisfies two basic democratic norms:

- No candidate should win an election if another candidate received more votes.

- Every vote should count the same.

- The norms are prime facie principles, that is, the burden of justification rests on those who disagree.

- A proponent of the Electoral System thus has the burden of justifying exceptions to the norms. For example, by completing sentences like:

- Yes, ordinarily the person with the most votes should win, but under some circumstances the winner should be someone who doesn’t get the most votes. Such exceptions are justified by the fact that …..

- Yes, ordinarily votes should count the same, but under some circumstances one person’s vote should count more than others. Such exceptions are justified by the fact that …..

Standard Arguments

Standard Arguments for the Electoral College

- EC better represents small states and sparsely populated areas, which would be ignored if the president was directly elected. If the election were by popular vote, candidates would be motivated to limit their campaigns to heavily-populated areas.

- EC provides presidential nominees a reason to select vice presidential running mates from a region other than their own.

- EC contributes to the political stability of the nation by encouraging the two party system.

- If the election were based on popular vote, a candidate might get the most votes without winning a majority, as happened with Nixon in 1968 and Clinton in 1992. EC precludes the need for run-off elections or a national recount.

Standard Arguments against the Electoral College

- EC violates the principle that the winner of an election should have more votes than any other candidate.

- Four presidents—Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, Benjamin Harrison in 1888, George W. Bush in 2000, and Donald Trump in 2016—were elected with fewer popular votes than their opponents

- EC violates One Person One Vote, the principle that everyone’s vote should count the same.

- For example, a vote for president in Wyoming has four times the weight of a vote in Texas. So one vote in WY is equivalent to four votes in TX.

- EC is biased against third parties and independent candidates

- For example Ross Perot won 19 percent of the popular vote in 1992 but no electoral votes.

- Under EC, citizens may forgo voting in states where one party is dominant.

- Under EC, candidates focus on swing states, with little reason to campaign in states that are solidly red or blue.

- Under EC, US citizens in Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories cannot vote for president, since US territories have no electoral votes.

- Under EC, enough faithless electors could change the results of an election.

- Possibility of Faithless Electors

- In the 2016 presidential election two of Trump’s electors (from Texas) voted for someone other than Trump and five of Clinton’s electors (four from Washington and 1 from Hawaii) voted for someone other than Clinton.

- Washington state fined its four faithless electors $1,000 each, which was appealed to the Supreme Court.

- Chiafalo v Washington

- “The Constitution’s text and the Nation’s history both support allowing a State to enforce an elector’s pledge to support his party’s nominee—and the state voters’ choice—for President.”

- A state “can demand that the elector actually live up to his pledge, on pain of penalty.”

- Chiafalo v Washington

National Popular Vote (NPV)

- States that join the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) pass a law that awards all their electoral votes to the candidate who wins the national popular vote – once the law is activated, which is when the total electoral votes of all the participating states is at least 270. So far 15 states and DC with 195 electoral votes have joined. 75 more electoral votes and NPV goes into effect.

Website

Arguments for and against NPV

- The arguments for and against NPC vs the current electoral college system are, for the most part, the same as the arguments for and against a constitutional amendment establishing the direct popular election of the President versus the current electoral college.

- One difference between NPV and a constitutional amendment is that the former is easier to pass. But it’s also easier to rescind.

- Another difference regards plurality and majority. A constitutional amendment would probably require the winner to receive a majority of the vote. But NPV requires only a plurality.

- There’s also the question whether the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact requires the consent of Congress, per Article I Section 10.

- “No State shall, without the Consent of Congress, lay any Duty of Tonnage, keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace, enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.”

- Arguments on the legal issue can be found in:

- The National Popular Vote (NPV) Initiative: Direct Election of the President by Interstate Compact

- NPV—The National Popular Vote Initiative: Proposing Direct Election of the President Through an Interstate Compact

- Wikipedia on the Legality of the NPV

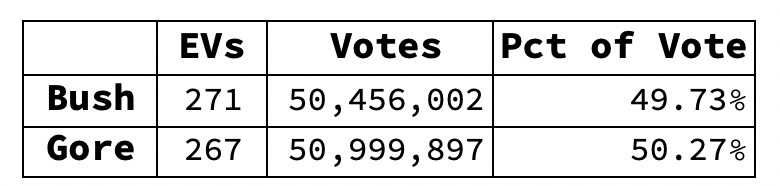

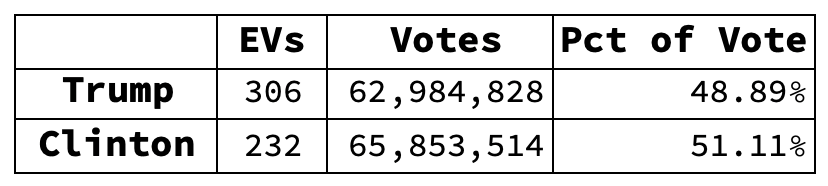

Rerun of 2000 Presidential Election

(Percent of Vote is the percent of the two-party vote.)

Result if a state’s electoral votes are awarded to candidates, as whole numbers, in proportion to their popular vote in the state

Result if a state’s electoral votes are awarded to candidates, as decimal fractions, in proportion to their popular vote in the state

- My calculations are virtually identical with those in Chapters 3 and 4 of Every Vote Equal: A State-Based Plan for Electing the President by National Popular Vote, 2013, by John R. Koza, Barry Fadem, Mark Grueskin, Michael S. Mandell, Robert Richie, and Joseph F. Zimmerman.

- The fractional proportional method fails because the number of a state’s electoral votes per million votes varies from state to state.

- Here’s an example:

- In the 2020 presidential election 504,346 were cast in Delaware and 276,765 in Wyoming. Both states have 3 electoral votes. Suppose that candidate X got 55 percent of the vote in Delaware and 43 percent in Wyoming.

- The result would have been this:

- X won 49 percent of the six electoral votes

- 2.94 / 6 = 0.49

- Yet won 50.75 of the popular vote

- 396399 / 781111 = 0.50748

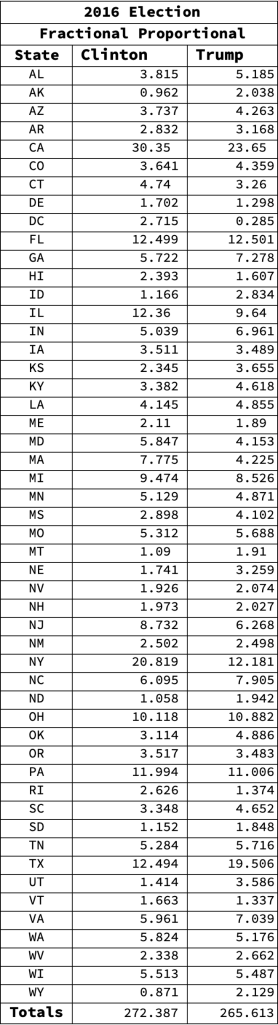

Rerun of 2016 Presidential Election

(Percent of Vote is the percent of the two-party vote. Electoral votes ignore faithless electors.)

Result if a state’s electoral votes are awarded to candidates, as decimal fractions, in proportion to their popular vote in the state: