Back to Scientific Theories

Contents

- Overview

- Basic Concepts

- Postulates

- Postulates Diagrammed

- Divergence and Curl

- Prediction of Electromagnetic Waves

- Magnetism: Three Levels of Explanation

- Electromagnetic Units of Measurement

- Brief History of the Theory of Electromagnetism

- Applications

Overview

The Theory of Electromagnetism is the theory of the electromagnetic force.

Basic Concepts

Electric Charge

- Electric charge is the ultimate source of all electric and magnetic phenomena.

- Coulomb articulated the idea of electric charge mathematically in the 1780s. In qualitative terms the idea is that:

- Charges are either positive or negative, in varying degrees.

- Like charges repel and unlike charges attract such that

- The larger the charge, the greater the attraction and repulsion.

- The closer the charges to each other, the greater the attraction and repulsion.

- Electric charge is an intrinsic property of elementary particles.

- Electrons have a negative charge equal to e, the elementary charge (1.602 × 10−19 coulomb).

- Quarks have a charge of either +2/3e or −1/3e.

- Protons have a positive charge equal to e by virtue of the charges of their constituent quarks

- (2/3e + 2/3e − 1/3e = 1e).

- Atoms become charged when they gain or lose electrons, making them ions.

- Large objects too become charged when they gain or lose electrons. Rubbing a glass rod with a silk cloth, for example, can tear electrons from atoms on its surface, leaving a net positive charge.

Electric Current

- An electric current is the flow of electric charge, such as the flow of electrons in a wire or ions through a solution.

- The unit of electric current is the ampere, equal to one coulomb of electric charge passing a point in one second.

- The direction of an electric current, by convention, is the direction of the flow of positive charges and the opposite direction of the flow of negative charges.

Current Loop (Magnet)

- A magnet is basically a current loop, the flow of electric charge around a loop.

- Current loops include

- the intrinsic spin of elementary particles such as electrons and quarks

- electrons orbiting a nucleus

- the flow of electrons through a coil of wire, such as those in solenoids, electromagnets, and transformers.

- The direction of a current loop is defined by the right-hand grip rule: with fingers of the right hand wrapped around the loop in the direction of the (positive) current, the thumb points in the direction of the loop.

Vector

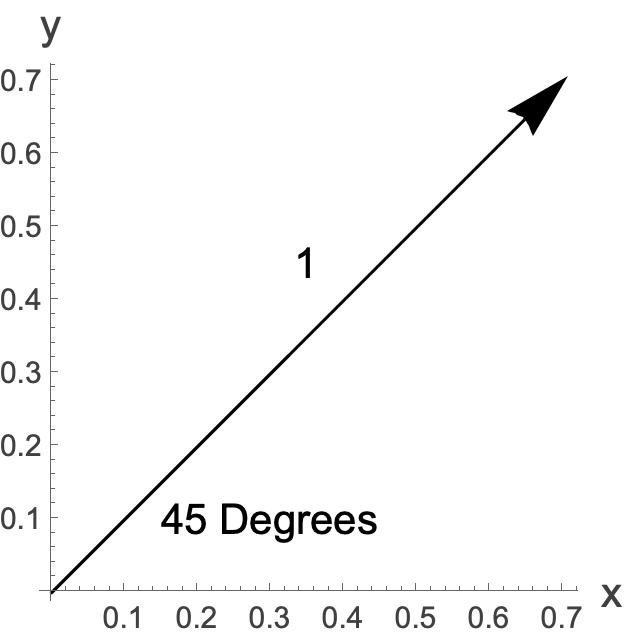

- A vector is an abstract entity with magnitude and direction (but no position). They are naturally visualized as arrows.

- Vectors can be added, subtracted, multiplied by a plain number (a scalar), and multiplied by another vector (resulting in a dot or cross product).

- In electromagnetic theory vectors represent currents, current loops, and (most importantly) fields.

Fields

- Faraday and Maxwell introduced the fundamental concept of a field into physics.

- Newton’s Law of Universal Law of Gravitation presupposes that the force of gravity acts directly and instantaneously, no matter how great the distance. (Though Newton himself thought the idea of instantaneous action at a distance was “so great an absurdity.”)

- For Faraday and Maxwell, however, electric and magnetic forces are transmitted as fields through space at the speed of light.

- A field is a region of space within which every point has an associated physical quantity. The quantity can be a scalar (a plain number), such as height in feet above sea level, or a vector, such as the speed and direction of the wind.

- Faraday and Maxwell postulated two vector fields: the electric and magnetic fields.

- Maxwell’s Equations describe how the fields are generated.

- The Lorentz Force Law describes how the fields exert a force on charged particles.

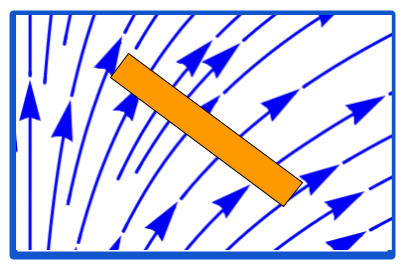

- A field can be visualized as a stream of arrows:

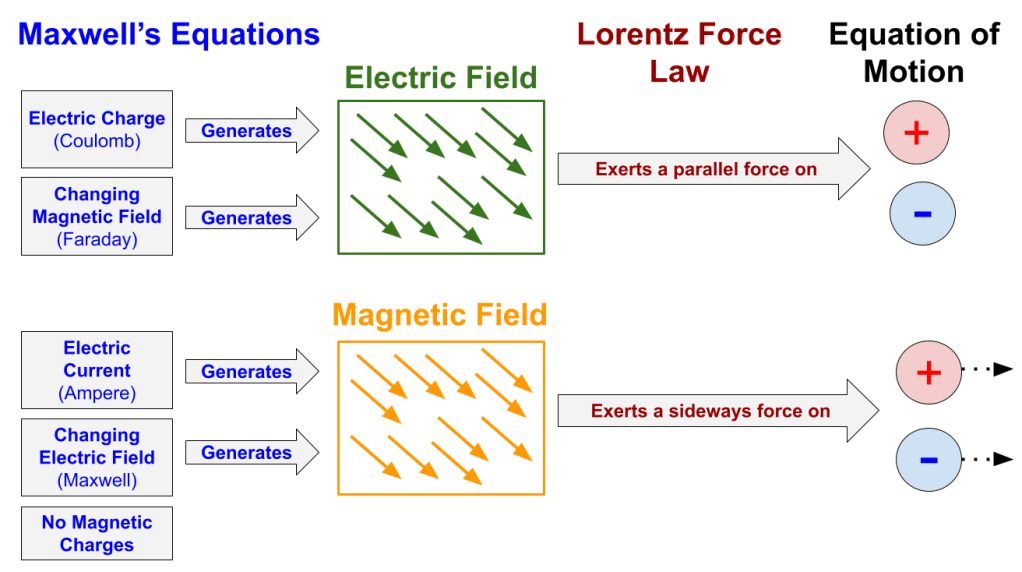

Postulates

- Maxwell’s Equations describe how electric and magnetic fields are generated.

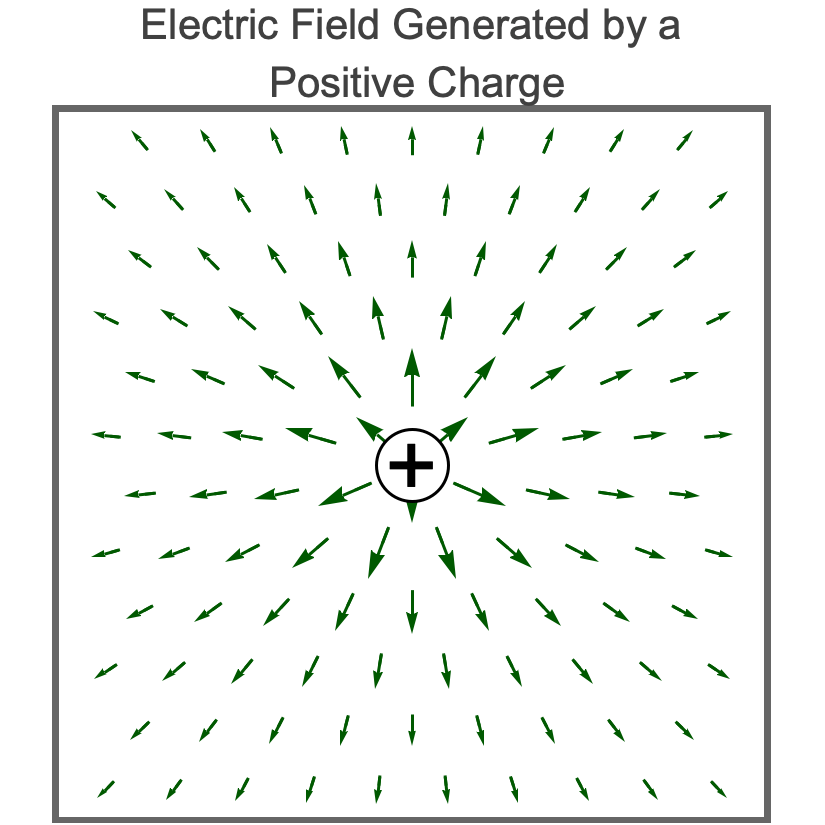

- An electric charge generates an electric field.

- A magnetic field changing with time generates an electric field.

- An electric current generates a magnetic field.

- An electric field changing with time generates a magnetic field.

- The Lorentz Force Law describes how electric and magnetic fields exert forces.

- An electric field exerts a parallel force on a charged particle.

- A magnetic field exerts a sideways force on a charged particle in motion.

- Newton’s Equation of Motion describes how a force makes a particle move.

- F = MA

Lorentz Force Law

- Roughly Put

- The electric Lorentz Force exerts a parallel force on a charged particle.

- The magnetic Lorentz Force exerts a sideways force on a charged particle in motion.

- Formula

- F = qE + qv × B

- F is force

- in newtons in SI units

- E is an electric field

- which is force per charge, that is, newtons/coulomb in SI units, or equivalently volts/meter.

- B is a magnetic field

- which is force per charge in motion, that is, the tesla in SI units, which equals 10,000 gauss in cgs units

- q is the electric charge of a particle

- in coulombs in SI units

- is either positive or negative

- v is is the velocity of a particle

- in meters/second

- qv × B is the cross product of vectors qv and B

- F is force

- F = qE + qv × B

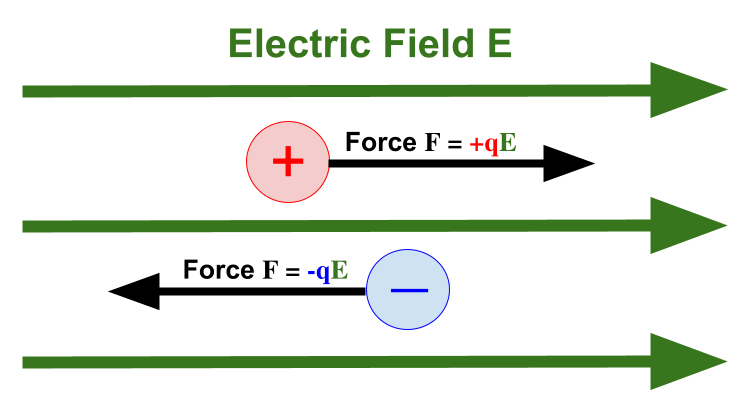

Electric Force F = qE in Ordinary Language

- An electric field E exerts a force F on a particle with charge q.

- The direction of the force is the direction of E if q is positive and the opposite direction of E if q is negative.

- The magnitude of the force is E times q.

Magnetic Force F = qv × B in Ordinary Language

- A magnetic force B exerts a force F on particle with charge q moving with velocity v.

- The direction of the force is determined by the right-hand cross rule: with the index finger pointing in the direction of the particle’s motion and the middle finger pointing in the direction of the magnetic field, the thumb points in the direction of the force.

- The magnitude of the force is the product of B, qv, and Sin[θ]

- where θ is the angle between the direction of the particle’s velocity v and the direction of the magnetic field B. (So the smaller θ is, the smaller the force.)

View Video of a charged particle moving in a magnetic field

- The Lorentz Force Law is true in all inertial reference frames. But the same instance of the Lorentz force acting on a particle may be due to an electric field in one frame, to a magnetic field in a second frame, and to a combination of the two in a third frame. The electromagnetic force is thus the force of both electricity and magnetism.

- View Reference Frames

Coulomb’s Law

- Roughly Put

- An electric charge generates an electric field

- Formula

- div E = ρ/ε0, for any point in space

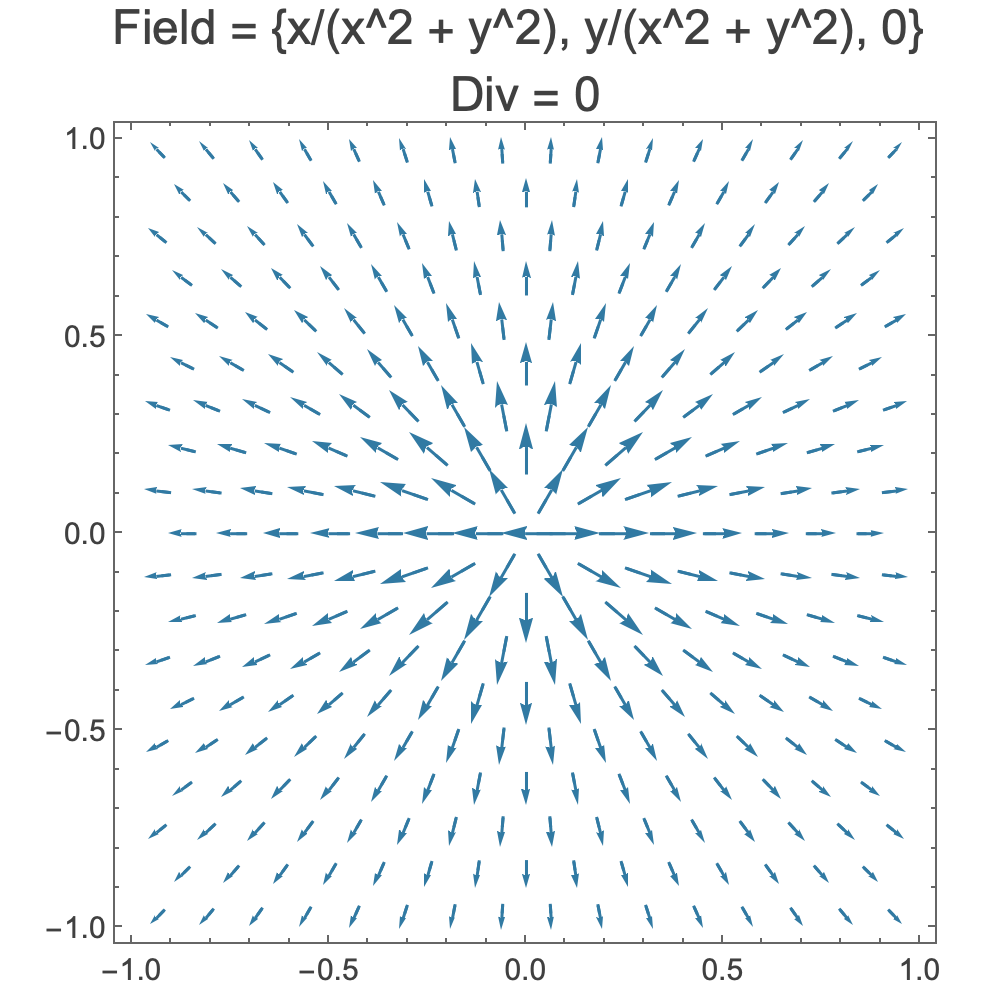

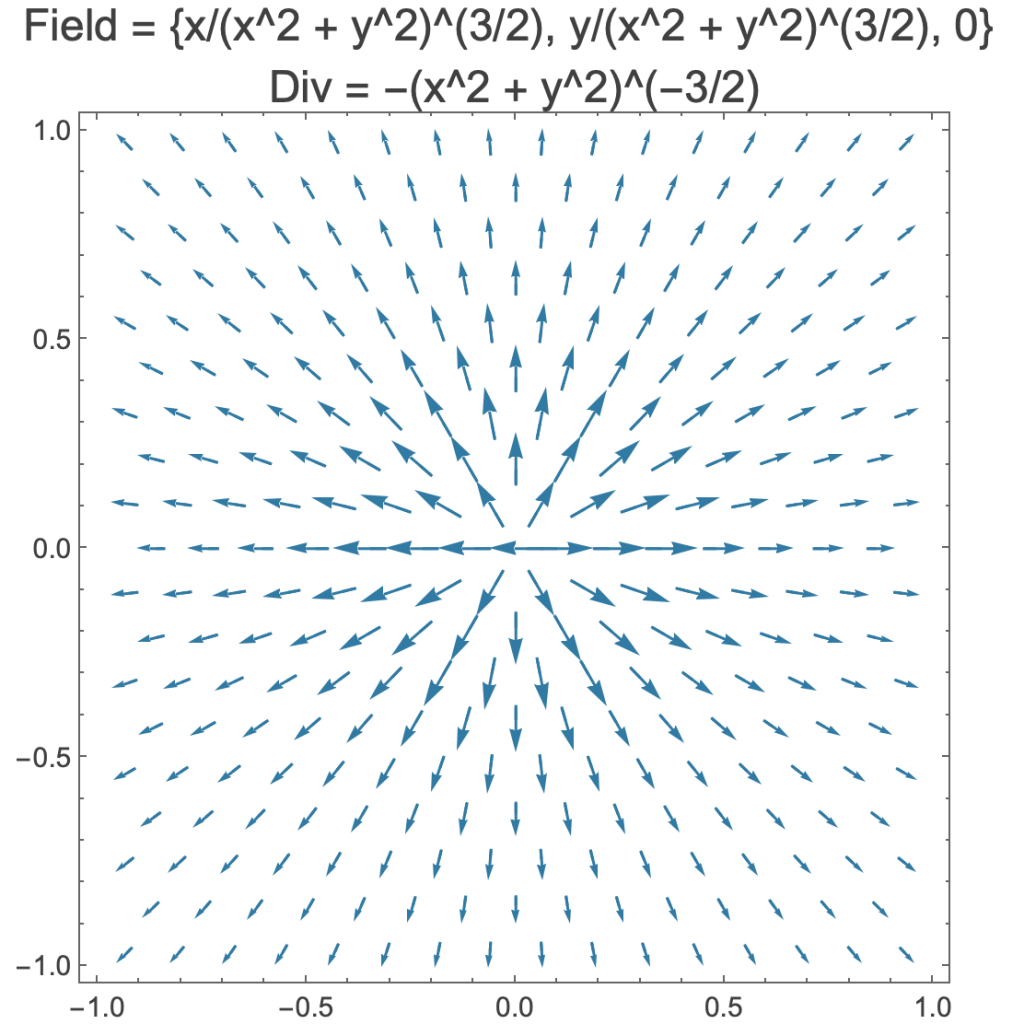

- div is divergence, the degree that a vector field emanates from or disappears into a given point

- View Divergence and Curl

- E is an electric field

- in newtons per coulomb

- ρ is charge density

- in coulombs per cubic meter

- ε0 is a physical constant, the permittivity of free space.

- div is divergence, the degree that a vector field emanates from or disappears into a given point

- div E = ρ/ε0, for any point in space

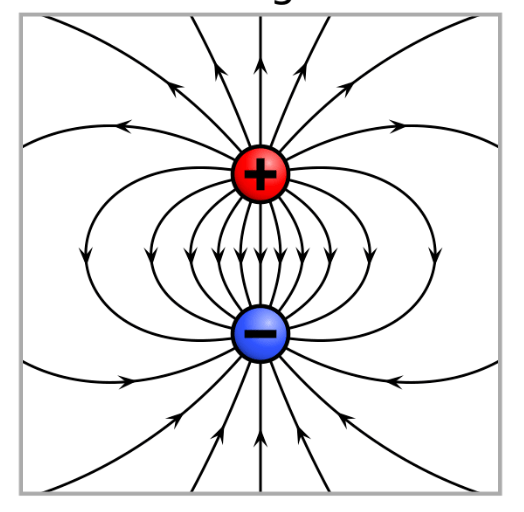

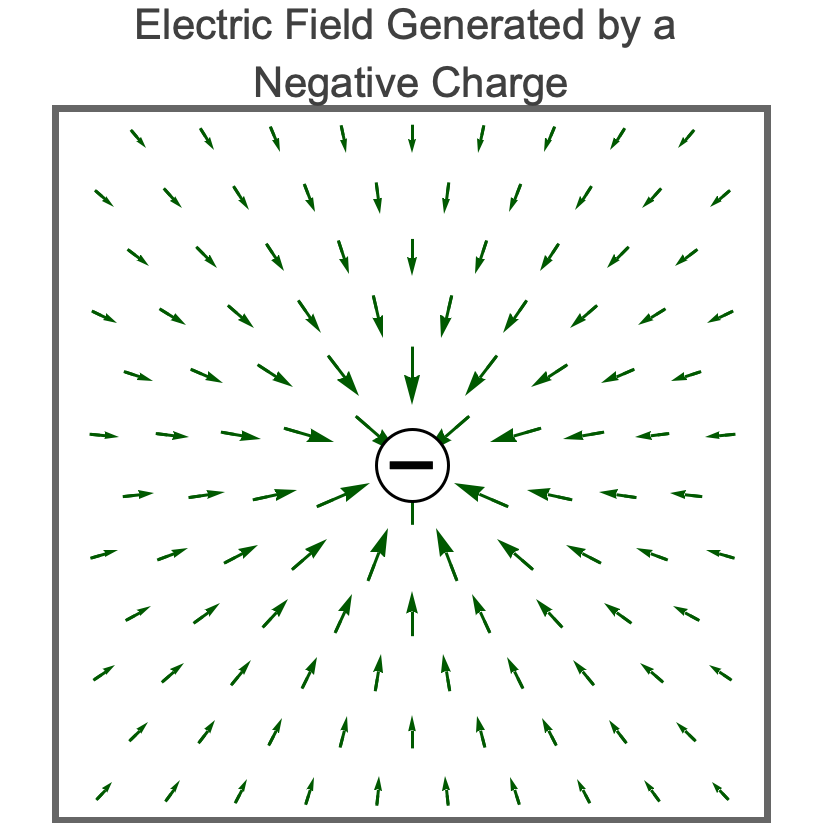

- Formula in Ordinary Language

- An electric field emanates from a positive electric charge and disappears into a negative electric charge.

- An electric field weakens as the distance from its field-generating charge increases.

View Interactive Electric Field for Two Charges

- Suppose there’s a charge q at a given location. Draw an imaginary sphere of radius r around the charge. Assuming the electric field is spherically symmetric, Coulomb’s Law implies that the electric field at any point on the sphere is E = q/(4πe0r2) directed radially outward. Which is equivalent to the force law Coulomb set forth:

- F = q1q2/(4πε0r2).

Faraday’s Law of Induction

- Roughly Put

- A magnetic field changing with time generates an electric field.

- Formula

- curl E = -∂B/∂t, for any point in space

- the curl of a vector field is its local rotation at a point

- View Divergence and Curl

- E is an electric field

- B is a magnetic field

- ∂B/∂t is the rate B changes with time

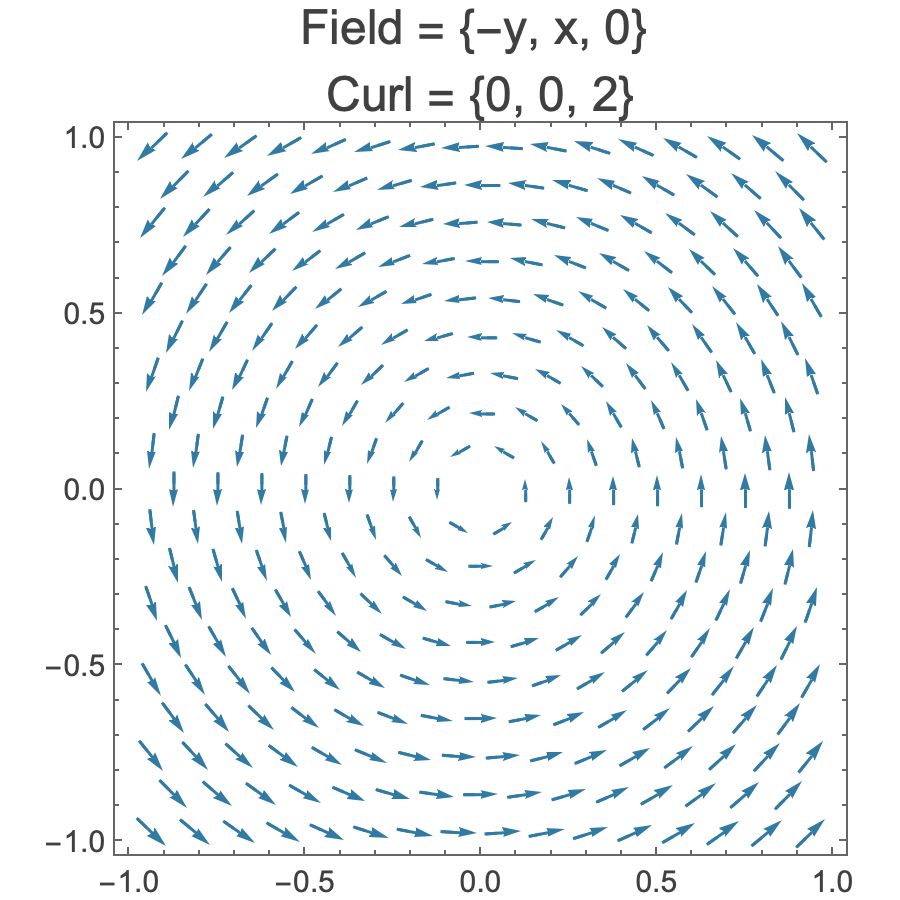

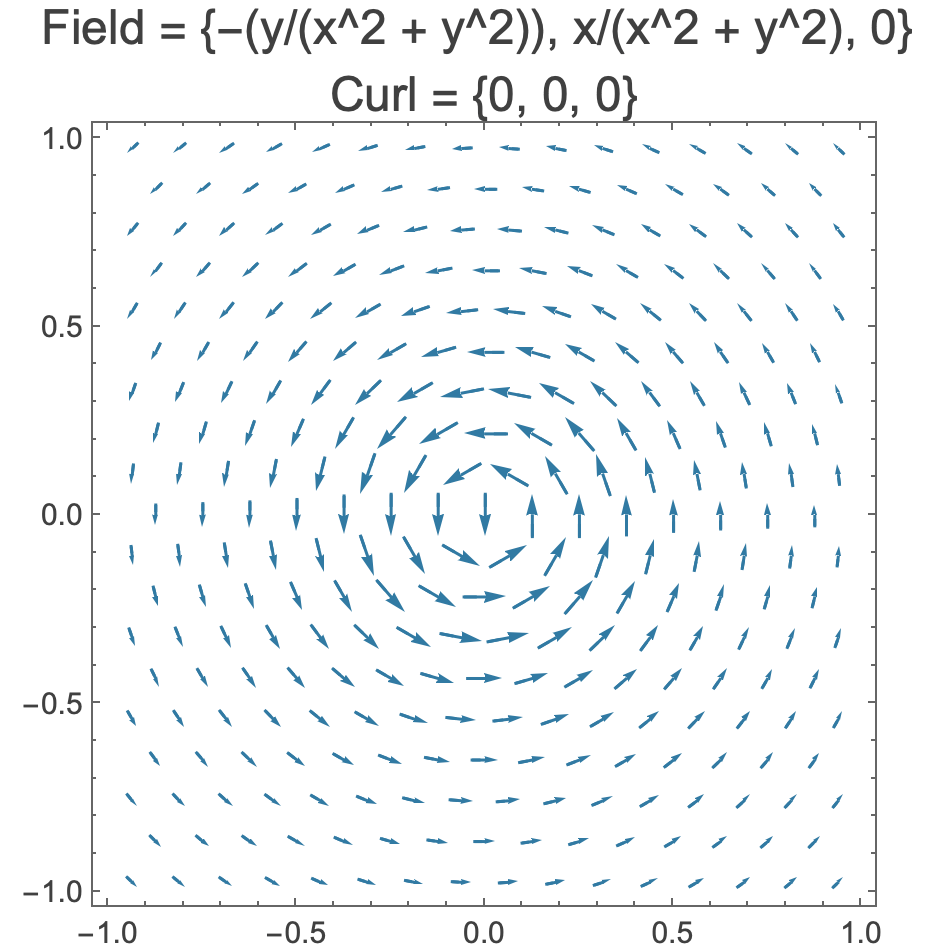

- the curl of a vector field is its local rotation at a point

- curl E = -∂B/∂t, for any point in space

- Formula in Ordinary Language

- A magnetic field changing with time generates an electric field circling around it.

- The direction of the electric field (because of the negation sign) is opposite to the right-hand grip rule, that is, with the thumb of the right hand pointing in the direction of the increasing magnetic field, the fingers curl around the magnetic field in the opposite direction of E.

- The magnitude of the electric field is the rate at which B changes with time.

- A bar magnet moving back and forth inside a coil of wire produces a changing magnetic field which, per Faraday’s Law, generates an electric field that extends through the coil, creating an electric current in the wire. Since the magnetic field in the diagram is increasing leftward, the generated current is counterclockwise relative to the magnet.

Ampere-Maxwell Law

- Roughly Put

- An electric current or a changing electric field generates a magnetic field.

- Ampere’s Law

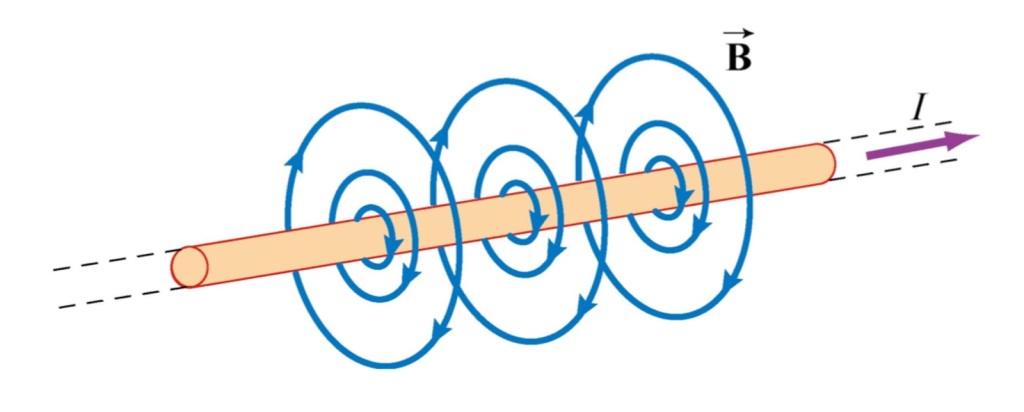

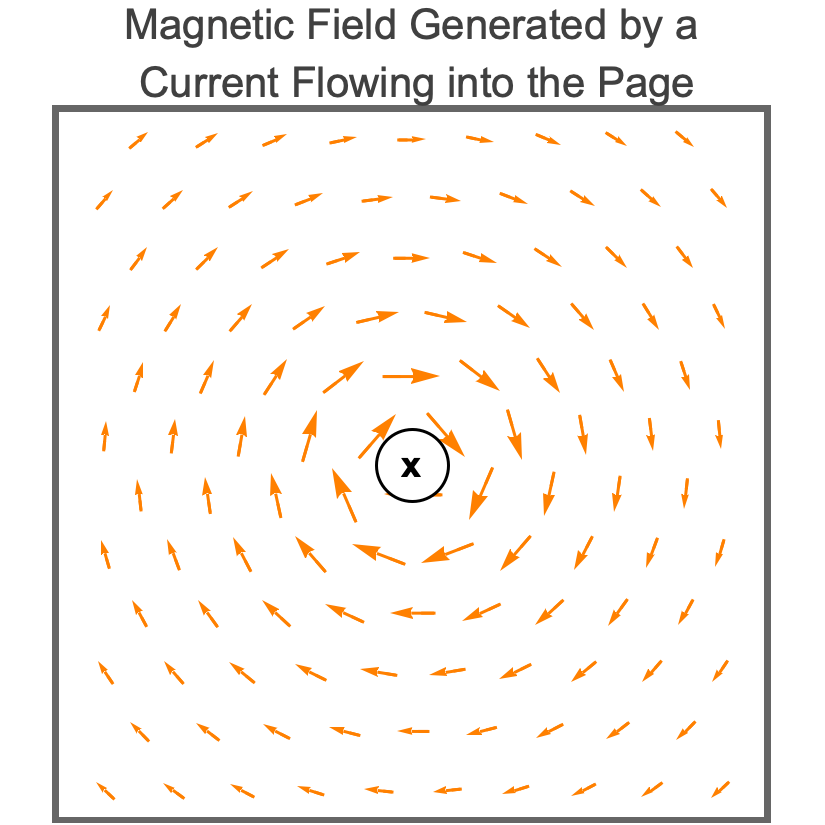

- An electric current in a wire generates a magnetic field rotating around the wire.

- Maxwell’s Law

- An electric field changing with time generates a magnetic field rotating around the electric field.

- Ampere’s Law

- An electric current or a changing electric field generates a magnetic field.

- Formula

- curl B = μ0J + μ0ε0 ∂E/∂t, for any point in space

- the curl of a vector field is its local rotation at a point

- View Divergence and Curl

- B is a magnetic field

- in teslas

- J is current density

- in amperes / square meter

- E is an electric field

- in newtons / coulomb

- ∂E/∂t is the rate E changes with time

- μ0 is a physical constant, the permeability of free space

- ε0 is a physical constant, the permittivity of free space

- the curl of a vector field is its local rotation at a point

- curl B = μ0J + μ0ε0 ∂E/∂t, for any point in space

- Curl B = μ0J in Ordinary Language

- An electric current generates a magnetic field rotating around it.

- The direction of the magnetic field is according to the right-hand grip rule, that is, with the thumb of the right hand pointing in the direction of the current, the fingers curl around the current in the direction of B.

- The magnitude of the magnetic field is proportional to the speed of the current.

- Curl B = μ0ε0 ∂E/∂t in Ordinary Language

- An electric field changing with time generates a magnetic field circling around it.

- The direction of the magnetic field is according to the right-hand grip rule, that is, with the thumb of the right hand pointing in the direction of the increasing electric field, the fingers curl around E in the direction of B.

- The magnitude of the magnetic field is proportional to the rate E changes with time.

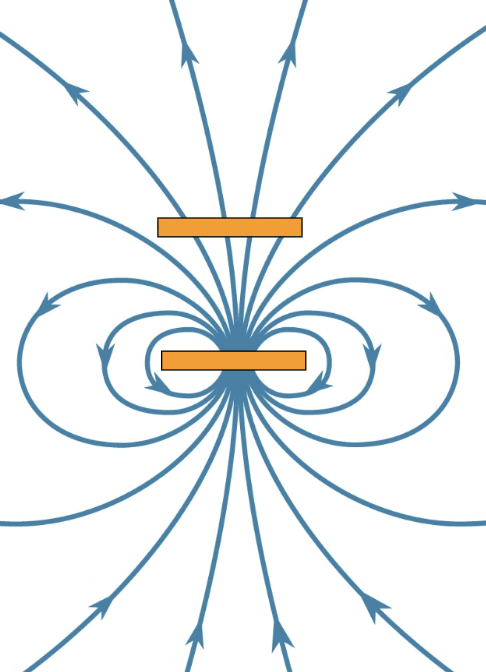

No Magnetic Charge Law

- Roughly Put

- There are no magnetic charges.

- Formula

- div B = 0, for any point in space

- div is divergence, the degree that a vector field emanates from or disappears into a given point

- View Divergence and Curl

- B is the magnetic field

- in teslas

- div is divergence, the degree that a vector field emanates from or disappears into a given point

- div B = 0, for any point in space

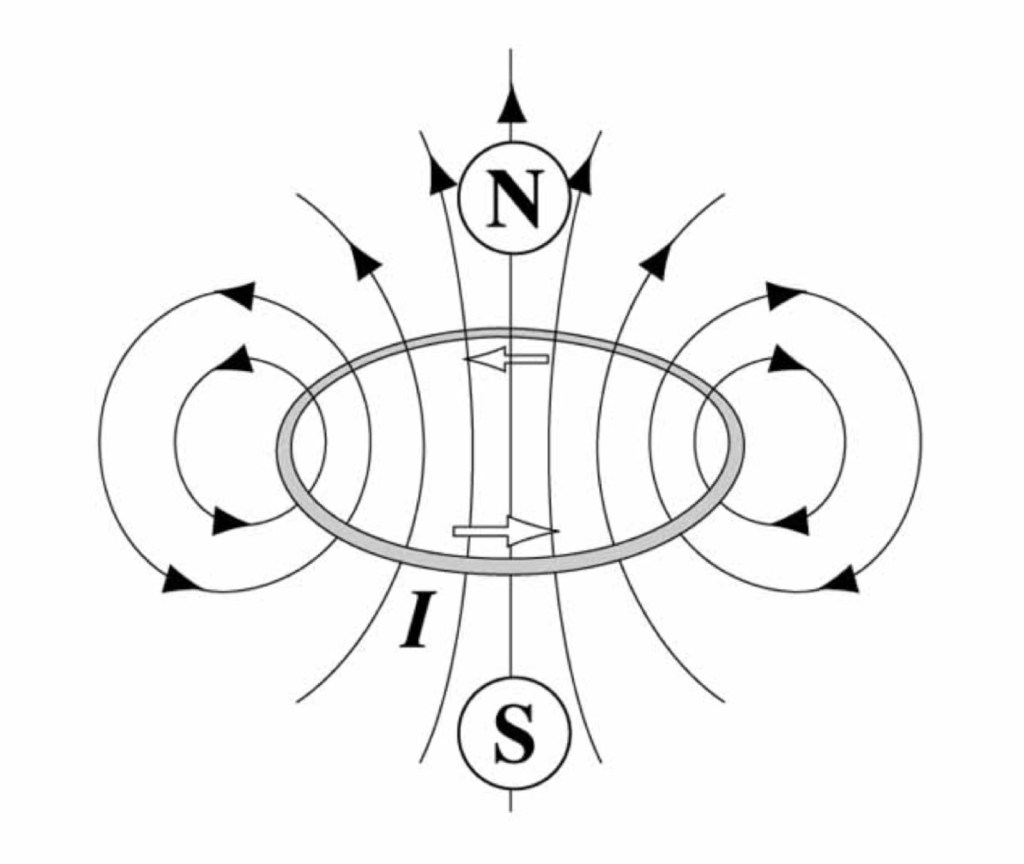

- Formula in Ordinary Language

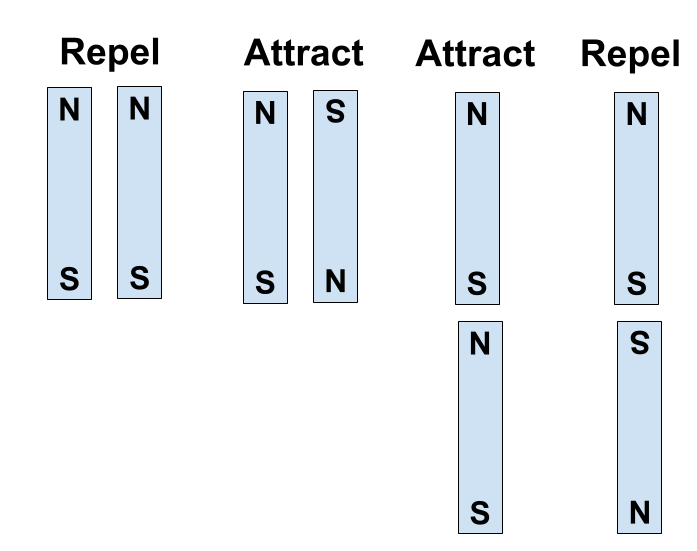

- Magnetic fields neither begin nor end.

- Magnetic fields only loop.

- Electric lines of force run from positive charges to negative charges. To be clear, they start at positive charges and end at negative charges.

- Magnetic lines of force (seemingly) run from north poles to south poles. But they neither start at north poles nor end at south poles. Magnetic lines of force start and end nowhere. They loop.

- A magnet is a current loop. Per Ampere’s Law, its circulating electrons generate a magnetic field that circles around and through the loop.

- Magnetic lines of force thus leave the north pole of a magnet, circle around to the south pole, and then, inside the magnet, return to the north pole.

Equation of Motion (Newton)

- Roughly Put

- Forces make particles move

- Formula

- F = ma

- Or, a = F/m

- Formula in Ordinary Language

- The acceleration a of a particle equals the net force F on it divided by its mass m.

- Which is to say that the rate at which the velocity of the particle changes with time equals the net force on the particle divided by its mass:

- Using the magic of differential equations, the future location, velocity, and acceleration of the particle can be calculated from its initial location and velocity.

Postulates Diagrammed

Divergence and Curl

Divergence and Curl are Spatial Rates of Change, not Temporal

- Maxwell’s Equations use two kinds of rates of change:

- time rate of change

- for example, the rate of change of the electric field per second, ∂E/∂t

- spatial rate of change

- for example, the rate of change of the electric field per meter

- time rate of change

- Divergence and Curl are the second kind.

Divergence and Curl are Local, not Global

- Divergence is the local expansion and contraction of a vector field

- Curl is the local rotation or circulation of a vector field.

Three globally-expanding vector fields with positive, zero, and negative divergence

Three globally circulating vector fields with positive, zero, and negative curl

Measuring Divergence with a Div-meter

- A div-meter is a make-believe instrument for measuring the divergence of a vector field at a point. The two-dimensional model consists of four positive charges arranged in a square. The upper and lower charges are connected by a vertical elastic cord; the left and right charges are connected by a horizontal elastic cord. The div-meter measures divergence by measuring the tension in the cords. If the tension increases in a cord, the field is expanding along the axis of the cord. If the tension decreases in a cord, the field is contracting.

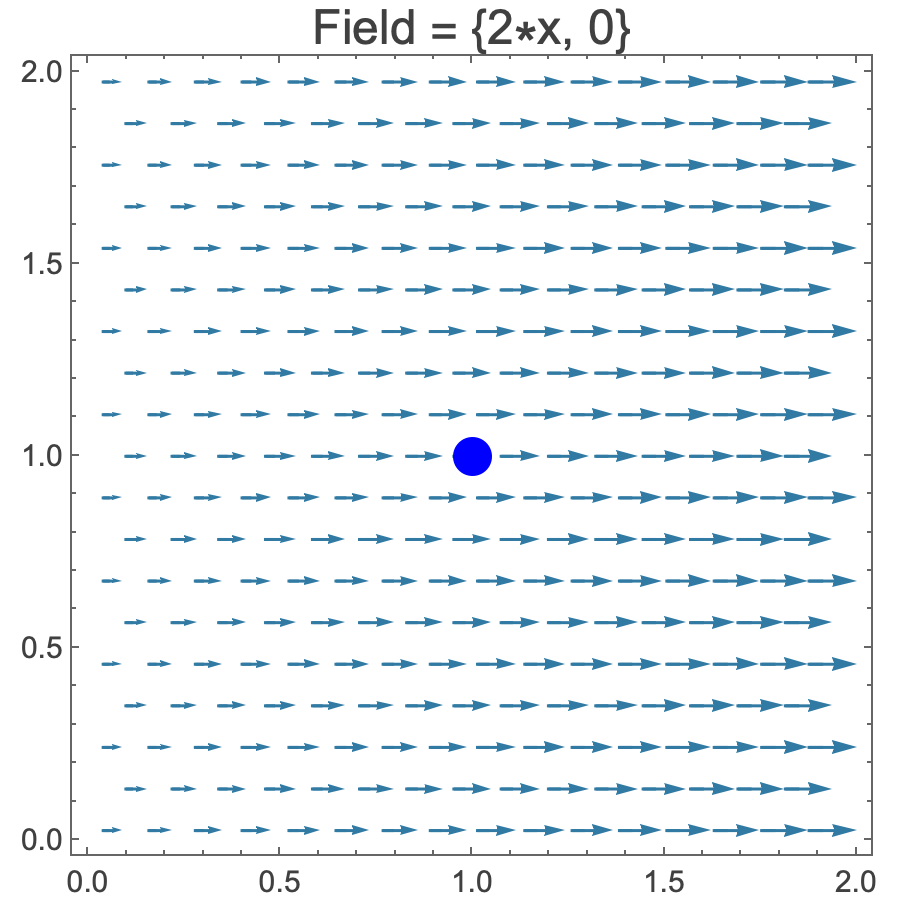

- Here’s a plot of the electric field E = {2x,0}. We want to find the divergence at point (1,1), where the dot is. We’ll use a div-meter.

- The div-meter is placed at point (1,1). The electric field E exerts a force on each of the div-meter’s positive charges, pushing them to the right. The forces on the top and bottom charges have the same magnitude, 2. But the force on the charge on the right (3) is greater than the force on the left charge (1), thus increasing the tension in the cord between them. E thus diverges at point (1,1) along the x-axis The magnitude of the divergence can be estimated by dividing the difference in the charges by the difference in their locations on the x-axis:

- (3 – 1)/(1.5 – 0.5) = 2.

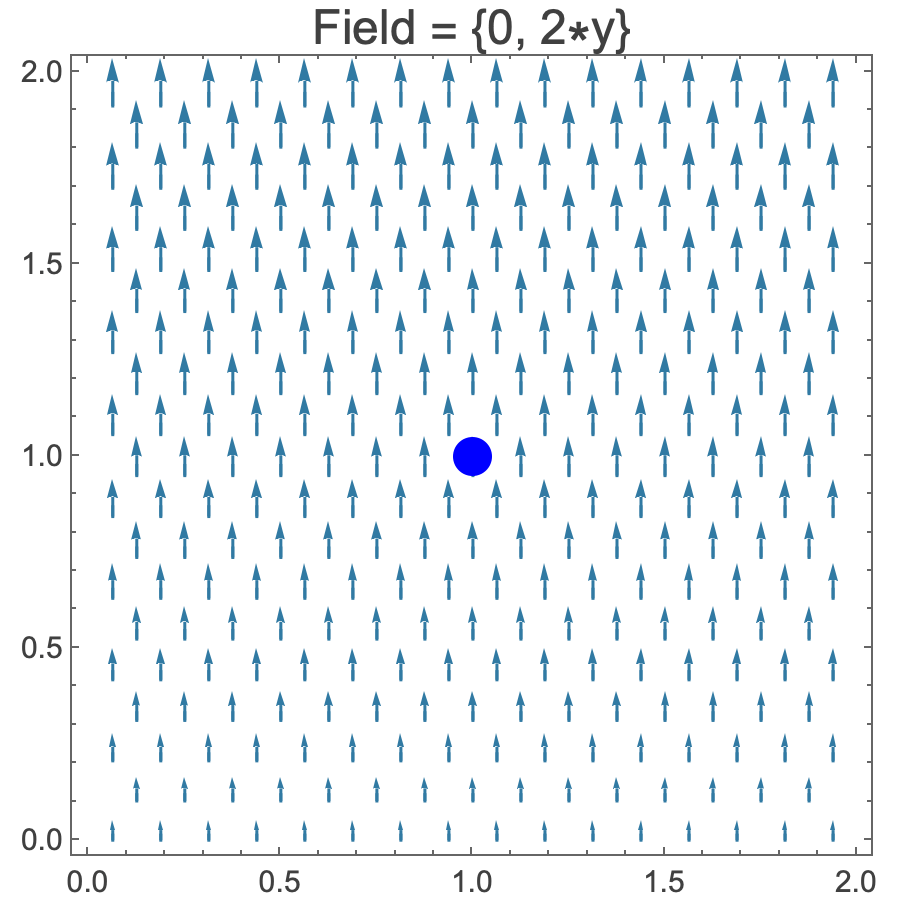

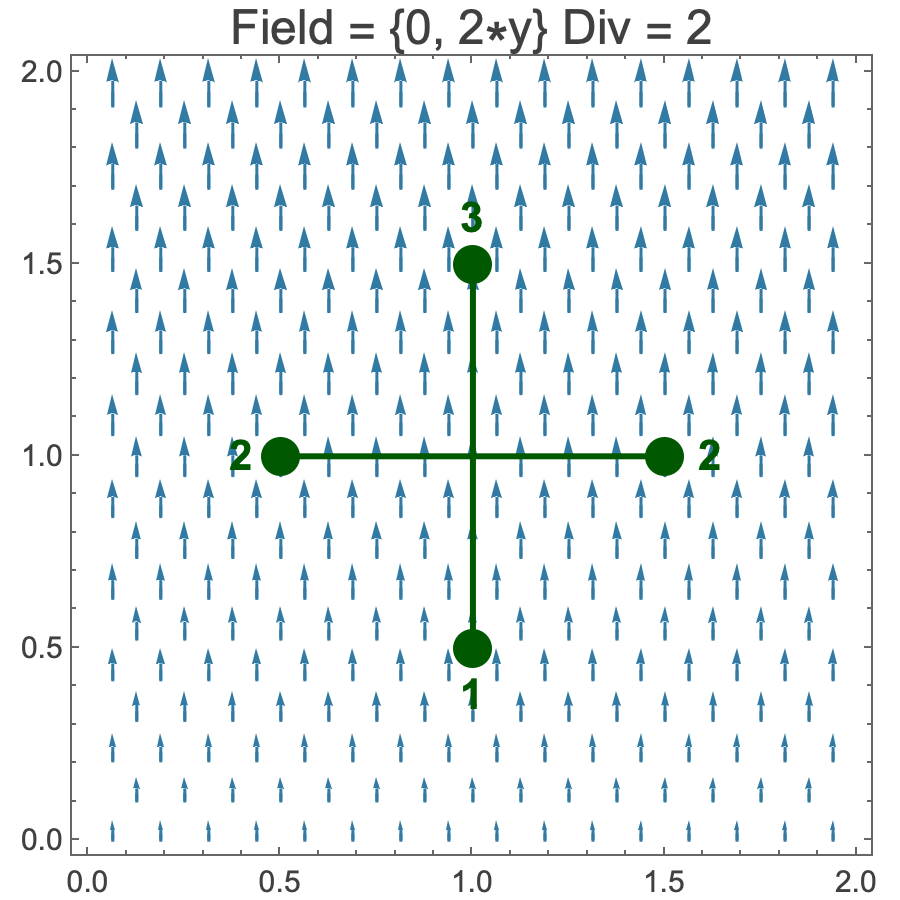

- Let’s try a different electric field, {0,2y).

- The div-meter is again placed at point (1,1). As before, the electric field E exerts a force on each of the div-meter’s positive charges, this time pushing them upward. The forces on the left and right charges have the same magnitude, 2. But the force on the top charge (3) is greater than the force on the bottom charge (1), thereby increasing the tension in the cord between them. E thus diverges at point (1,1) along the y-axis The magnitude of the divergence can be estimated by dividing the difference in the charges by the difference in their locations on the y-axis:

- (3 – 1)/(1.5 – 0.5) = 2.

- The div-meter measurements accord with the definition of divergence in two-dimensional Cartesian coordinates:

- ∇・E = ∂Ex/∂x + ∂Ey/∂y

- In the first example, {2x,0}, the definition yields:

- ∂Ex/∂x + ∂Ey/∂y = ∂2x/∂x + ∂0/∂y = 2 + 0 = 2.

- And in the second example, {0,2y}, the definition yields:

- ∂Ex/∂x + ∂Ey/∂y = ∂0/∂x + ∂2y/∂y = 0 + 2 = 2

- As a final example, let’s combine the earlier cases. Thus, E = {2x,2y).

- The div-meter at point (1,1) looks like this. The force on each charge has two components, (x, y). We compute the divergence first along the x-axis and then along the y-axis.

- The x-values for the top and bottom charges are the same, 2. But the magnitude of the right charge, 3, is greater than that of the left charge, 1. So the divergence along the x-axis = 2, as in the first example.

- The y-values for the left and right charges are the same, 2. But the magnitude of the top charge, 3, is greater than that of the bottom charge, 1. So the divergence along the y-axis = 2, as in the second example.

- The (total) divergence, then is:

- ∂Ex/∂x + ∂Ey/∂y = ∂2x/∂x + ∂2y/∂y = 2 + 2 = 4.

- The extension to three dimensions is straightforward. Using a 3D div-meter, we measure the divergence at a point (x, y, z) by measuring the divergence along the three axes and summing the results.

- That is

- ∇・E = ∂Ex/∂x + ∂Ey/∂y + ∂Ez/∂z

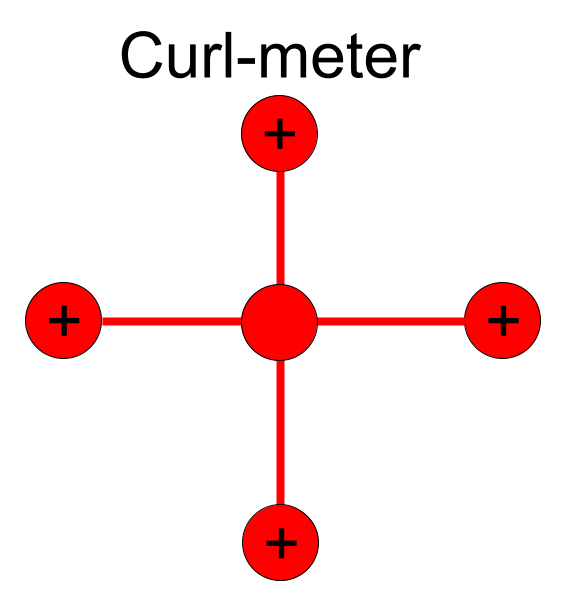

Measuring Curl with a Curl-meter

- A curl-meter is a make-believe instrument for measuring the curl of an electric field at a point. The two-dimensional model is a tiny paddlewheel that uses positive charges as paddles. Depending on the magnitude and direction of the electric forces on each of the four charges, the curl-meter (1) rotates around its central hub clockwise at a given angular velocity, (2) rotates around the hub counter-clockwise at a given angular velocity, or (3) does not rotate.

- Later we’ll use the three-dimensional model.

- Here’s a plot of a two-dimensional electric field E = {0, 2x}. We want to find the curl at point (1,1), where the dot is. We’ll use a 2D curl-meter.

- The curl-meter is placed at point (1,1). The electric field E exerts a force on each of the curl-meter’s positive charges, pushing them upward. The forces on the top and bottom charges have the same magnitude, 2. But the force on the right charge (3) is greater than the force on the left charge (1), making the curl-meter rotate counter-clockwise. The magnitude of the curl can be estimated by dividing the difference in the charges by the difference in their locations on the x-axis:

- (3 – 1)/(1.5 – 0.5) = 2.

- Let’s consider a second example, the electric field E = {2y, 0}, which exerts a force on each of the curl-meter’s positive charges, pushing them to the right. The forces on the left and right charges have the same magnitude, 2. But the force on the upper charge (3) is greater than the force on the lower charge (1), making the curl-meter rotate clockwise. The magnitude of the curl can be estimated by dividing the difference in the charges by the difference in their locations on the y-axis:

- (3 – 1)/(1.5 – 0.5) = 2.

- Except that the curl in this case is -2, as we’ll explain in the next example.

- The crazy field on the right combines the two examples. That is, E = {2y, 2x}.

- So what’s the curl at point (1,1)?

- It turns out that the curl of E = {2y, 2x} is zero. The reason is that the field makes the arms of the curl-meter rotate in opposite directions.

- The force on each charge has two components, (x, y). I first consider the x-component of the force.

- The x-force on the left and right and charges are the same, 2. But the x-force on the top charge, 3, is greater than that on the bottom charge, 1. So the x-component of the force makes the curl-meter rotate clockwise. Its magnitude = 2, as in the second example.

- Now the y-component of the force.

- The y-force on the top and bottom charges are the same, 2. But the y-force of the right charge, 3, is greater than that on the left charge, 1. So the y-component of the force makes the curl-meter rotate counterclockwise, as in the first example.

- The two forces, counterclockwise and clockwise, counteract and nullify each other. Thus the curl = 0. This is accomplished mathematically by making the second force negative. That is:

- ∇ x E = ∂Ey/∂x – ∂Ex/∂y = ∂2x/∂x – ∂2y/∂y = 2 – 2 = 0

- I’ll now use a 3D curl-meter to calculate the curl of an electric field at point (1,1,1).

- Curl in three dimensions is a vector, i.e. the vector (i, j, k) where i is the rotation of the field around the x-axis, j its rotation around the y axis, and k its rotation around the z axis.

- The example I use is the electric field E = (z, x, -y). As we’ll see the curl = (-1, 1, 1).

- I first calculate the electric field at each of the six positive charges. Then I calculate the rotation of the field around each of the z, y, and z axes.

- Here are three views of E = (z, x, -y):

- We locate the curl-meter at point (1,1,1).

- The six positive charges are 0.5 units from (1,1,1) along the three axes.

- Each charge is labeled with the electric field at its location. The field at the uppermost charge, for example, is {1.5, 1, -1), meaning that there’s a force of 1.5 units on the charge in the positive x direction, a force of 1 unit in the positive y direction, and a force of 1 unit in the negative z direction.

- I first determine the curl around the z-axis.

- The objective is to figure out how the red part of the curl-meter rotates (if at all) in the xy-plane.

- First, look at the x-component of the field at the four (red) charges. The field equals 1 at each charge. So the x-component has no effect on the curl-meter.

- Now look at the y-component of the field. At the near and far charges the y-component = 1. So they have no effect. But the y-component at the right charge = 1.5 and at the left charge it’s 0.5. So the right charge moves in the positive y-direction, making the curl-meter rotate around the z-axis. The magnitude of the force is:

- (1.5 – 0.5)/(1.5 – 0.5) = 1.

- The sign of the curl is determined by the right-hand grip rule: Curl the fingers of your right-hand around the z-axis in the direction of the rotation and, in this case, your thumb points in the positive z-direction.

- So the curl of the field along the z-axis = +1.

- Next I determine the curl around the y-axis.

- The curl-meter rotates, if at all, in the in the xz-plane.

- First look at the z-component of the field at all four (red) charges. It equals -1 in each case. So the z-component of E has no effect on the curl-meter.

- Now look at the x-component of the field. At the left and right charges the x-component = 1. So it has no effect. But the x-component at the top charge = 1.5 and at the bottom charge it’s 0.5. So the top charge moves in the positive x-direction, making the curl-meter rotate around the y-axis. The magnitude of the force is:

- (1.5 – 0.5)/(1.5 – 0.5) = 1.

- The sign of the curl is determined by the right-hand grip rule, which in this case is in the positive y-direction

- So the curl of the field along the y-axis = +1.

- Lastly I determine the curl around the x-axis.

- The curl-meter rotates, if at all, in the in the yz-plane.

- First look at the y-component of E at the four (red) charges. In each case it equals 1. So the y-component has no effect on the curl-meter.

- Now look at the z-component of the field. At the top and bottom charges the z-component = -1. So it has no effect. But the z-field at the far charge = -1.5; at the near charge it equals -0.5. So the far charge moves in the negative z-direction, making the curl-meter rotate around the x-axis. The magnitude of the force is:

- (1.5 – 0.5)/(1.5 – 0.5) = 1.

- The sign of the curl is determined by the right-hand grip rule, which in this case is in the negative x-direction

- Thus the curl of the field along the x-axis = -1.

- The results of the 3D curl-meter accord with the definition of curl in three-dimensional Cartesian coordinates.

- ∇ x F = (∂Ez/∂y – ∂Ey/∂z)i + (∂Ex/∂z – ∂Ez/∂x)j + (∂Ey/∂x – ∂Ex/∂y)k,

- Thus, where E = (z, x, -y):

- ∇ x F = (∂-y/∂y – ∂x/∂z)i + (∂z/∂z – ∂-y/∂x)j + (∂x/∂x – ∂z/∂y)k

- ∇ x F = (-1 – 0)i + (1 – 0)j + (1 – 0)k

- ∇ x F = (-1, 1, 1).

Prediction of Electromagnetic Waves

- Maxwell realized that his equations logically implied a phenomenon completely unknown at the time.

- Suppose that electrons travel back and forth in a straight wire from one end to the other, speeding up, slowing down, and momentarily stopping.

- Ampere-Maxwell’s Law implies that the back-and-forth motion of the electrons generates a continuously changing magnetic field.

- At this point a cycle begins:

- The changing magnetic field produces a changing electric field, per Faraday’s Law of Induction.

- The changing electric field produces a changing magnetic field, per the Ampere-Maxwell’s Law.

- The mutually-generating magnetic and electric fields propagate through space as a wave.

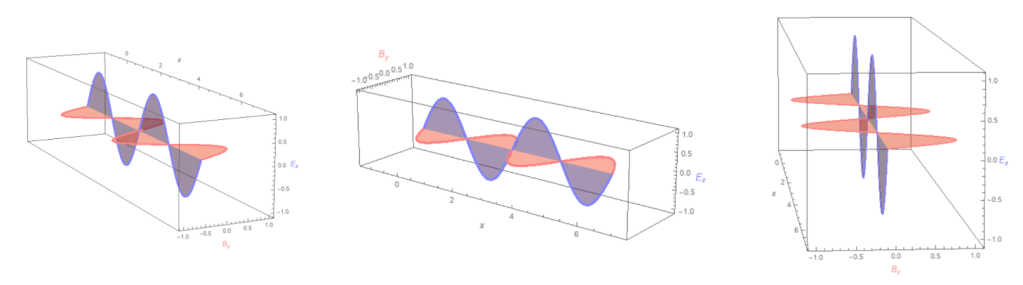

The Result is an Electromagnetic Wave

Propagation of a Plane Electromagnetic Wave

The electric wave is bluish. The magnetic wave is reddish.

View Animation

Historical Note: Faraday speculated in 1845 that oscillations in electric and magnetic lines of force would propagate as waves.

Maxwell’s Inference that Light is an Electromagnetic Wave

- From his equations Maxwell calculated that the speed of an electromagnetic wave was:

- v = √(1/(μ0ε0))

- where

- ε0 is a physical constant, the permittivity of free space, used in Coulomb’s Law

- ε0 = 8.8541878188 10-12

- μ0 is a physical constant, the permeability of free space, used in Ampere-Maxwell Law

- μ0 = 1.25664 10-6

- ε0 is a physical constant, the permittivity of free space, used in Coulomb’s Law

- Doing the math

- v = √(1/(μ0ε0)) = √(1/ (1.25664-6 x 8.8541878188 10-12)) = 299,792,458 meters per second = the speed of light

- Maxwell concluded that:

- “The agreement of the results seems to show that light and magnetism are affections of the same substance, and that light is an electromagnetic disturbance propagated through the field according to electromagnetic laws.”

- A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field, 1865

- “The agreement of the results seems to show that light and magnetism are affections of the same substance, and that light is an electromagnetic disturbance propagated through the field according to electromagnetic laws.”

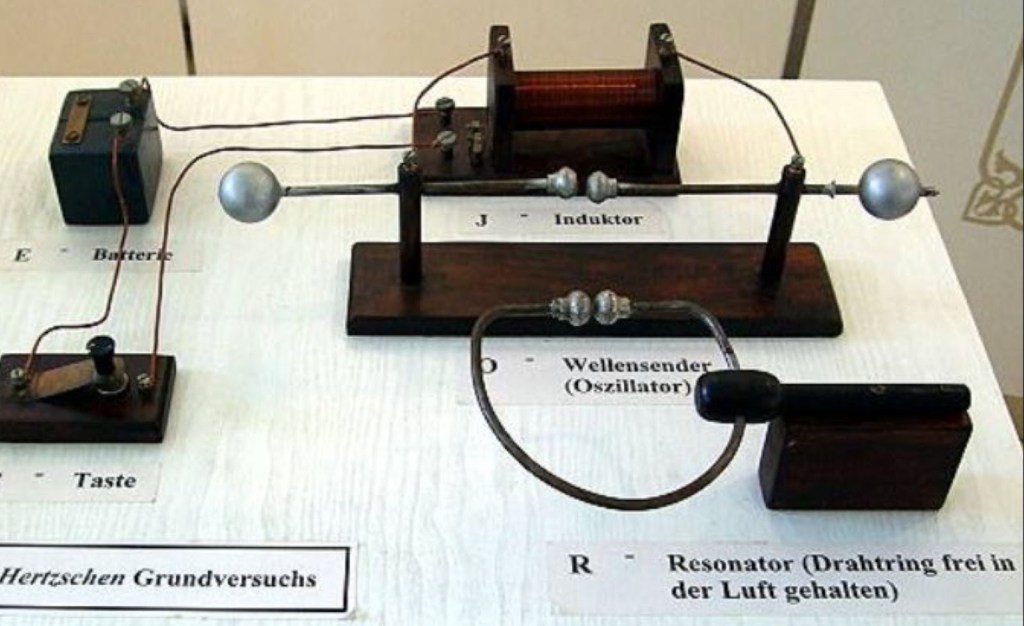

Confirmation of Maxwell’s Prediction of Electromagnetic Waves

In 1886 Heinrich Hertz confirmed Maxwell’s prediction of electromagnetic waves, by generating and detecting radio waves.

- Apparatus:

- Transmitter (Wellensender): a straight electrical wire about a yard long with a gap in the middle for a spark to cross.

- Attached to the the wire are a capacitor, inductor, and battery making what’s called an LC oscillator.

- Receiver (Resonator): a curved electrical wire about a yard long with a gap in the middle for a spark to cross.

- The receiver is in front of the transmitter in the photograph.

- Transmitter (Wellensender): a straight electrical wire about a yard long with a gap in the middle for a spark to cross.

- What Happens

- Electrons moving back and forth in the transmitter wire (and making sparks across its gap) generate radio waves.

- The radio waves make electrons move back and forth in the receiving wire (making sparks across its gap).

Magnetism: Three Levels of Explanation

- Three levels of explanation why magnets attract and repel:

- Magnetic Poles

- Magnetic Lines of Force

- Magnets as Current Loops

Magnetic Poles

- Like magnetic poles repel and opposite poles attract.

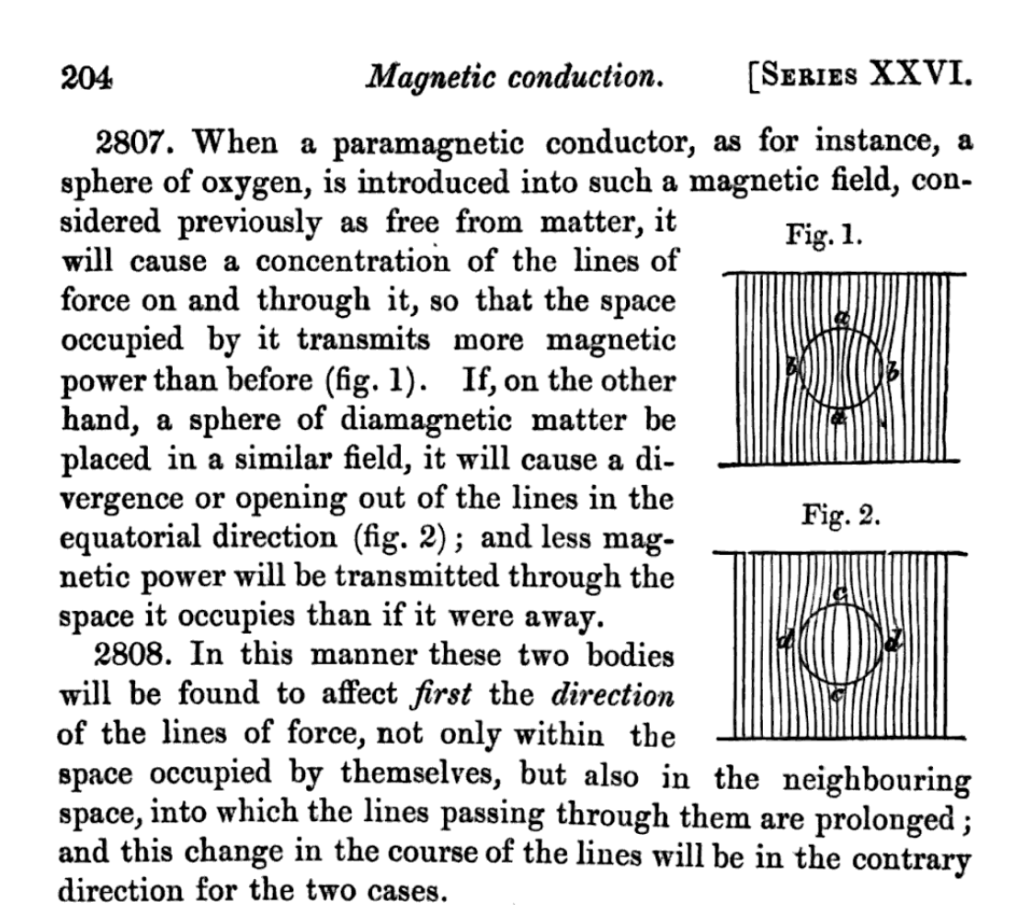

Magnetic Lines of Force

- Two-part explanation:

- A magnet generates a magnetic field, which can be depicted as lines of force.

- A magnet in a magnetic field aligns itself with lines of force.

- Thus, a bar magnet generates a magnetic field within which the needles of little compasses point in the direction of the lines of force.

Magnets as Current Loops

- A magnet is basically a current loop.

- So when two magnets — two current loops — are near each other:

- By Ampere’s Law each current loop creates a magnetic field

- By the Lorentz Force Law, the circulating current in each loop within the magnetic field of the other results in a force on each segment of the loop.

- I consider two scenarios.

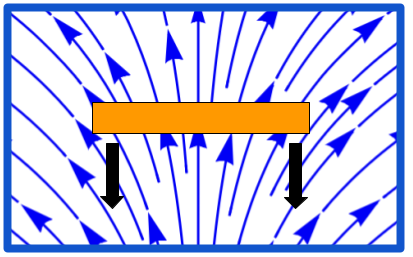

One Magnet North of the Other

- Suppose one magnet is above the other, oriented the same way:

- Which means that the current loops are thus:

- Each current loop generates a magnet field that encloses the other.

- Consider the case where the bottom loop’s magnetic field encloses the top loop:

- A close-up of the top loop.

- Look at the right side of the loop. The magnetic field points northeast, which means that a component of the magnetic field points outward to the right. Since the current flows into the page at that point, there’s a downward force on the right side of the loop per the Lorentz Force Law.

- Look at the left side of the loop. The magnetic field points northwest, which means that a component of the magnetic field points outward to the left. Since the current flows out of the page at that point, there’s a downward force on the left side of the loop per the Lorentz Force Law.

- So the upper loop experiences a downward force toward the lower loop.

- The same line of reasoning can be used to show that the lower loop experiences an upward force toward the upper loop. The main difference is that the lines of force through the lower ring converge rather than diverge and therefore a component of the magnetic field is inward rather than outward. There is thus an upward force on the loop per the Lorentz Force Law.

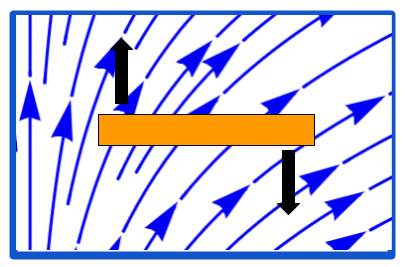

One Magnet Northeast of the Other

- Suppose that one magnet is northeast of the other.

- The current loop of the upper magnet is in the northeast quadrant of the lower loop’s magnetic field.

- A close-up of the upper loop:

- Look at the right side of the loop. The magnetic field points northeast, which means that a component of the magnetic field points outward to the right. Since the current flows into the page at that point, there’s a downward force on the right side of the loop per the Lorentz Force Law.

- Look at the left side of the loop. The magnetic field also points northeast, which means that a component of the magnetic field points inward to the right. Since the current flows out of the page at that point, there’s an upward force on the left side of the loop per the Lorentz Force Law.

- The two forces thus rotate the loop in the direction of the lines of force:

- The same reasoning can be used to show that lower magnet undergoes forces rotating it in the direction of the lines of force of the upper magnet’s magnetic field.

Electromagnetic Units of Measurement

Units

- Force (newton N) = mass x acceleration = kg m/s2

- Energy (joule J) = force x distance = kg m2/s2

- Power (watt W) = energy / time = kg m2/s3

- Charge (coulomb C) = current x seconds = A s

- Current (ampere A) = charge / second = C/s

- Electric Field = force / charge = N/C = V/m

- Magnetic Field (tesla T) = force / (charge x velocity) = N/(C m/s) = N/(A m)

- Curl of Field (∇ x field) = field / meter

- Divergence of Field (∇・field) = field / meter

- Electric Potential (Volt V) = force x (distance / charge) = (kg m/s2) (m/C) = energy / charge = (kg m2/s2) / C

- Gradient of Electric Potential (-∇Φ) = electric potential / distance = V/m = electric field

- Resistance (ohm Ω) = (kg m2) / (s3 A2)

- Capacitance (farad F) = charge / electric potential = C / V

- Flux = field x distance2

- Magnetic Flux (weber Wb) = magnetic field x m2 = N/(A m) m2

- Electric Flux = electric field x m2 = N/C m2 = V m

- Charge Density = charge / volume = C/m3

- Current Density = current / area = A/m2

- Permittivity of Free Space ε0

- 8.8541878188 × 10-12 m-3kg-1s4A2

- Permissibility of Free Space μ0

- 1.25663706 × 10-6 m kg s-2A-2

Laws

- Ohm’s Law

- I = V/R

- Current = voltage / resistance

- A = ((m2 kg)/(s3 A)) / ( (kg m2)/(s3 A2))

- Coulomb’s Law

- div E = ρ/ε0

- Electric field / meter = charge density / ε0

- ((kg m/s2)/C) / m = (C/m3) / (m-3 kg-1 s4 (C/s)2)

- Ampere’s Law

- curl B = μ0J

- Magnetic field / meter = μ0 current / area

- ((kg m/s2)/(A m)) / m = (kg m s-2A-2) A / m2

- Maxwell’s Law

- Curl B = μ0ε0 ∂E/∂t

- Magnetic field / meter = μ0ε0 electric field / time

- ((kg m/s2)/(A m)) / m = (m-3 kg-1 s4 A2) (m kg s-2 A-2) ((kg m/s2)/C) / s

- Faraday’s Law

- curl E = -∂B/∂t

- Electric field / meter = -magnetic field / time

- ((kg m/s2)/C) / m = ((kg m/s2)/(A m)) / s

Brief History of the Theory of Electromagnetism

- Before 1820 electricity and magnetism were regarded as unrelated phenomena.

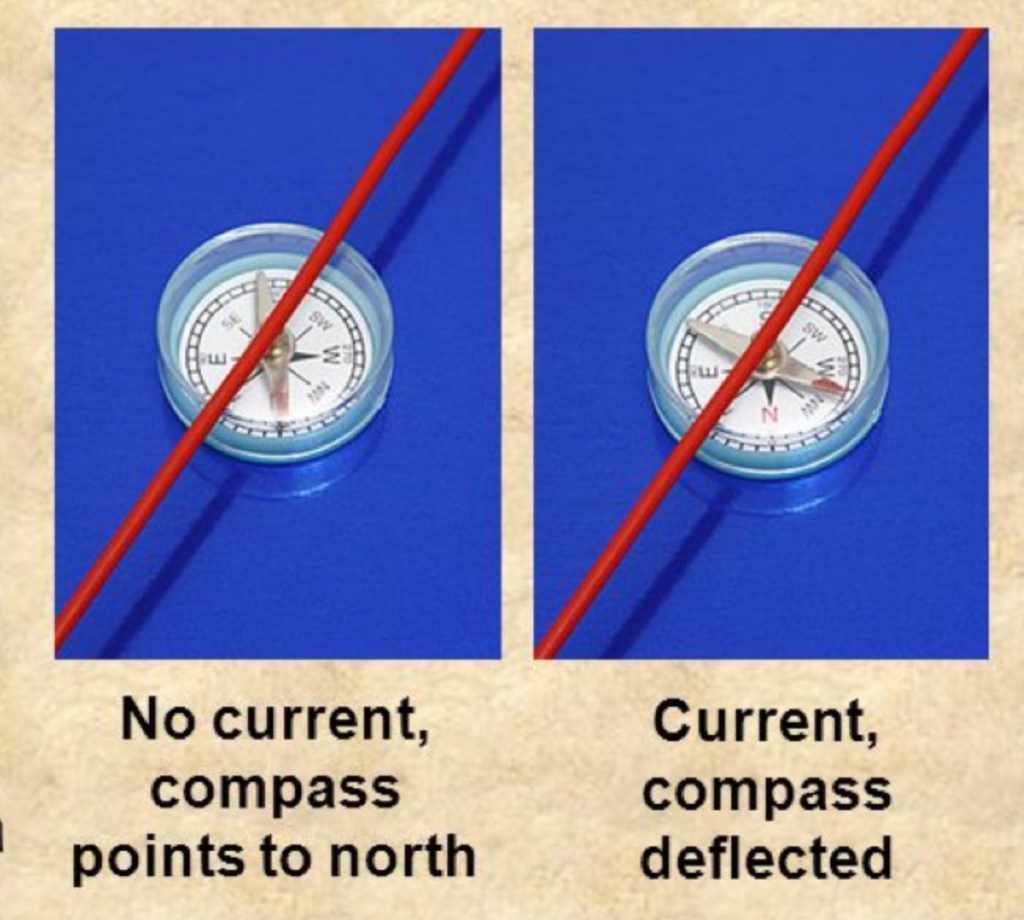

- 1820 Hans Christian Ørsted

- While setting up apparatus for a lecture, Ørsted noticed that the magnetic needle of compass near a current-carrying wire aligned itself perpendicular to the wire.

- 1821-1822 André-Marie Ampère

- Ampere set forth his theory that a magnet consists of tiny molecular “loops” of electric current.

- 1820-1855 Michael Faraday

- Faraday was from working class family with only a rudimentary education.

- At age 14 he was apprenticed to a bookbinder, which gave him access to books. Which he read.

- Faraday developed the basic idea of electromagnetism (with no mathematical background): that electric and magnetic forces are transmitted through fields (which he depicted as lines of force). Translating Faraday’s ideas into mathematics, James Clerk Maxwell put together the classical theory of electromagnetism.

- Faraday discovered his Law of Induction.

- He also made the first electric motor and the first electric generator.

- Faraday conjectured that light propagated as interacting lines of force.

- 1841 William Thomson (Lord Kelvin)

- At age 17 Thomson proved that Faraday’s lines of force could be represented mathematically by the same Fourier equations that govern the flow of heat in a metal bar.

- 1855-1875 James Clerk Maxwell

- At age 14 Maxwell published his first scientific paper. He attended the University of Edinburgh and the University of Cambridge.

- Maxwell read Thompson’s paper on Faraday’s lines of force and Faraday’s Experimental Researches in Electricity.

- He made it his mission to convert Faraday’s ideas into mathematical form. In the 1860s he published the mathematical theory of electromagnetism.

- From the postulates of the theory he derived one of the great predictions of science: the existence of electromagnetic waves.

- He died at age 48 in 1879 before his prediction was tested.

- His contemporaries didn’t understand his theory.

- The concept of a field was too revolutionary.

- The mathematics was new and complex

- Britannica:

- He is ranked with Sir Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein for the fundamental nature of his contributions.

- 1880-1890 Maxwellians (Oliver Lodge, GF FitzGerald, Oliver Heaviside, Heinrich Hertz)

- 1885 Having developed vector calculus, Oliver Heaviside reduced Maxwell’s twenty equations to the four known as Maxwell’s Equations

- 1886 Heinrich Hertz created radio waves, thus confirming Maxwell’s prediction of electromagnetic waves.

- 1905 Einstein

- Einstein set forth Special Relativity in his 1905 paper On The Electrodynamics Of Moving Bodies.

- When asked if he stood on the shoulders of Newton, Einstein replied “I stood on Maxwell’s shoulders.”

Applications

Electric Generator

- Michael Faraday made the first electric generator based on his Law of Induction (that a changing magnetic field produces a current in a wire).

- A coil of wire in a magnetic field is rotated (by hand, by wind, by whatever). As it rotates, the coil experiences a magnetic field that (from the coil’s perspective) is continuously changing in direction and magnitude. A current is thus generated by Faraday’s Law.

- The coil can be rotated by hand, by water pressure from a dam, by air pressure from a wind turbine, or by steam pressure from a coal plant or nuclear reactor.

Electric Motor

- Michael Faraday invented the electric motor, a simple but ingenious use of the Lorentz Force.

- An electric current passes through a coil of wire in a magnetic field. Per the Lorentz Force Law, electrons moving through a magnetic field experience a sideways force. The current going in one direction in the coil (green arrows in the diagram) experiences an upwards force (red arrows). The current going in the reverse direction experiences a downwards force. Combined, the forces make the coil rotate.

Ionization Smoke Detectors

- Smoke detectors are of two kinds: ionization detectors and photoelectric detectors. Here’s how ionization detectors work.

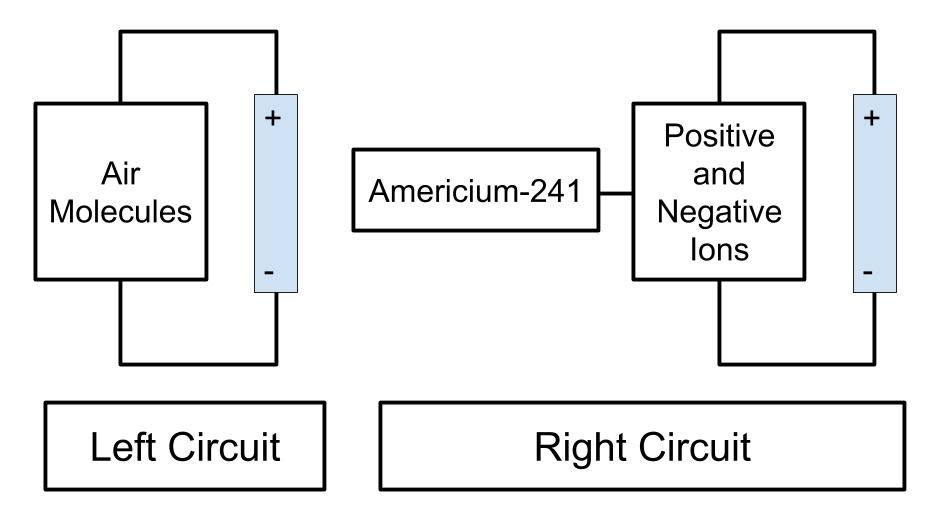

- In the Left Circuit, with a battery and a Chamber of air molecules, no current flows because the electrons in the wire cannot cross the Chamber.

- The Chamber of the Right Circuit consists of positive and negative ions, thanks to the attached supply of the radioactive element Americium-241.

- The Americium-241 sends alpha particles into the Chamber that knock electrons from oxygen and nitrogen atoms, turning them into positively charged ions while freeing electrons. Being charged, the ions and electrons carry electric current across the Chamber, completing an electric circuit.

- But any smoke particles entering the chamber combine with the ions, neutralizing them and disrupting the current. The system is rigged so that an alarm goes off if the current is reduced.

Electric Shocks

- The severity of a shock depends on the current, not the applied voltage. Duration also matters.

- By shuffling your feet on a carpet on a dry day, you can charge yourself up to 50,000 volts. But the shock you get won’t be lethal because the amount of charge is tiny. But a 120 V wall socket can kill you, since the amount of charge from the power company is limitless.

- The typical path of current through the human body is down an arm, though the chest, and down the legs.

- An electric current is dangerous because it can cause burns, paralysis of organs, and ventricular fibrillation.

- Currents as small 50 mA can cause fibrillation.

- A current of 10 mA running through your hand is the threshold for contracting your muscles so you can’t let go. Sweating makes things worse, reducing the resistivity of the skin.

- Dry skin provides more resistance to a shock than wet skin. The current from a 120 volt wall socket passing through wet skin may be 100 times greater than the current passing through dry skin.

- The majority of deaths occur from alternating current at house-current frequencies (60 hertz in North America and 50 hertz in Europe).

- Sources

- Electricity and Magnetism, 3rd edition, 2013, Purcell and Morin

- britannica.com/science/electrical-shock

Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter (GFCI)

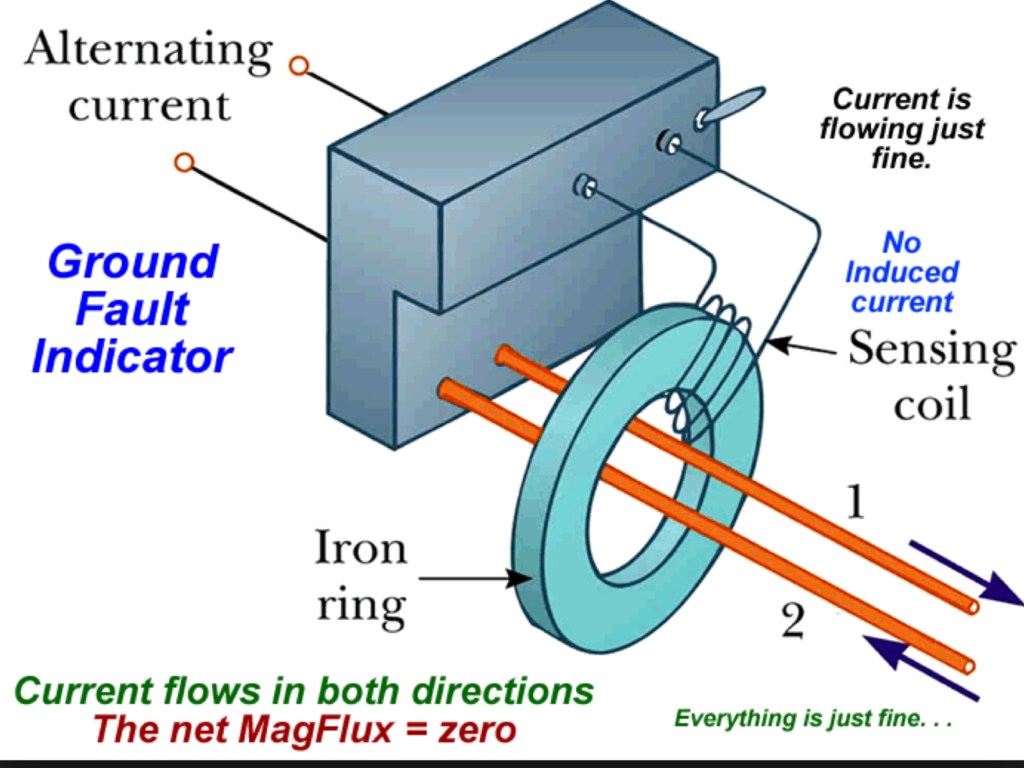

Circuit breakers protect buildings

GFCIs protect people

Flowing in opposite directions, the currents in the hot and neutral wires offset each other, preventing the production of a magnetic field in the Iron Ring.

If the current in one wire becomes greater than the other, a magnetic field is produced in the Iron Ring by Ampere’s Law. The increasing magnetic field through the Sensing Coil induces a current (by Faraday’s Law) that breaks the circuit.

Geomagnetism

- Electric currents within its liquid iron core effectively make Earth a magnet whose south pole is in the Arctic Ocean and whose north pole is off the coast of Antarctica.

- Since the opposite ends of magnets attract, the needle of a compass on Earth’s surface points “north” toward the south pole of Earth’s magnetic field.

Image Credit britannica.com/science/geomagnetic-field

- Earth’s magnetic poles reverse on average every 300,000 to a million years. Reversals take about 5,000 years.

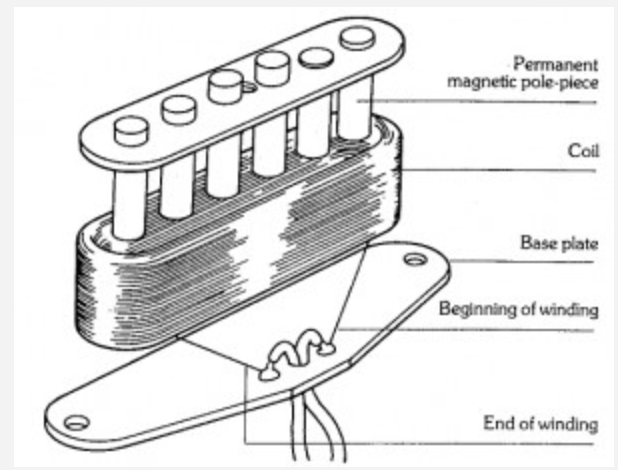

Pickups

- Electric pianos, violins, violas, cellos, basses, guitars, banjos, and mandolins generate sound using a system of pickups, amplifiers, and speakers.

- By Ampere’s Law, a current through the pickup’s coil produces a magnetic field.

- By Faraday’s Law of Induction, a steel string vibrating in a magnetic field produces a current in the string.

- The current goes to an amplifier and then to a speaker.