Back to Free Will and Determinism

People are able to do otherwise and that ability is incompatible with determinism

Outline

- Libertarianism

- What Free Will Looks Like

- Raising Your Arm of Your Own Free Will

- Neural Mechanisms of Action

- Altering the Course of Events in Your Brain

- What kind of being must a person be?

- Cartesian Interactionism

- Eccles’ Quantum Theory of Control

- Arguments for Free Will

- Fundamental Mechanisms of Action

Libertarianism

- Libertarianism is the view that

- People have free will

- A person decided or acted of their own free will if they could have decided or acted otherwise.

- Free will and determinism are incompatible.

- People have free will

- Libertarians include Rene Descartes, Roderick Chisholm, and John Eccles, Nobel laureate in neuroscience

- Different ways Libertarians characterize Libertarianism beyond “could have done otherwise.”

- A person decided or acted of their own free will if

- they could have decided or acted otherwise

- and their ability to decide or act otherwise was incompatible with determinism.

- A person decided or acted of their own free will at time T if they could have refrained from doing so under the conditions existing at time T

- A person decided or acted of their own free will if

- their decision or action was not determined by prior events and laws of nature

- their doing otherwise was also not determined by prior events and laws of nature

- A person decided or acted of their own free will if they could have done otherwise and in doing otherwise they would have altered the course of events in their brain.

- A person decided or acted of their own free will if

What Free Will Looks Like

- A person decided or acted of their own free will if they could have decided or done otherwise, that is, under the conditions existing at the time.

- Free will is thus branchy, with the fixed past branching into possible futures

Raising Your Arm of Your Own Free Will

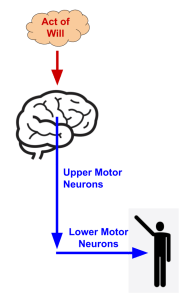

- When you raise your arm

- Upper motor neurons fire

- Which cause lower motor neurons to fire, releasing the neurotransmitter acetylcholine across synapses with muscles.

- Which cause the muscles to contract

- Which causes your arm to rise

- When you raise your arm, you cause the upper motor neurons to fire by a certain mental effort on your part to raise your arm, a mental act that’s variously called an act of will, an endeavoring, a trying, or a volition.

- When you raise your arm of your own free will it’s under your control whether the act of will takes place

- Your act of will is therefore not determined by laws of nature and prior events.

- And when you raise your arm of your own free will it’s under your control whether the upper motor neurons fire.

Neural Mechanisms of Action

- First Question

- How precisely does your act of will make the upper neurons fire?

- Descartes proposed a theory incorporating the pineal gland

- John Eccles has developed a more sophisticated theory incorporating Quantum Physics.

- How precisely does your act of will make the upper neurons fire?

- Second Question

- Is there any neuroscientific evidence for such mechanisms of action?

Altering the Course of Events in Your Brain

- A person decided or acted of their own free will if they could have done otherwise and in doing otherwise they would have altered the course of events in their brain.

- People can alter the course of events in their brain by performing mental acts that cause brain events, e.g. decisions and acts of will.

- Decisions

- After deliberating what to do, you make a decision. According to the Libertarian, the act of deciding causes a certain brain event that would not have otherwise occurred. A person has control over whether they decide one way or another. Therefore the person has control over whether the associated brain event occurs or not.

- Acts of Will

- Ludwig Wittgenstein asked “What is left over if I subtract the fact that my arm goes up from the fact that I raise my arm?” What is left over is an act of will. Per the Libertarian, an act of will causes a certain brain event. Like a decision, a person has control whether an act of will occurs. So the person has control over whether the associated brain event occurs and whether their arm goes up or not.

- Acts of will are also referred to as: volitions, undertakings, endeavorings, and tryings

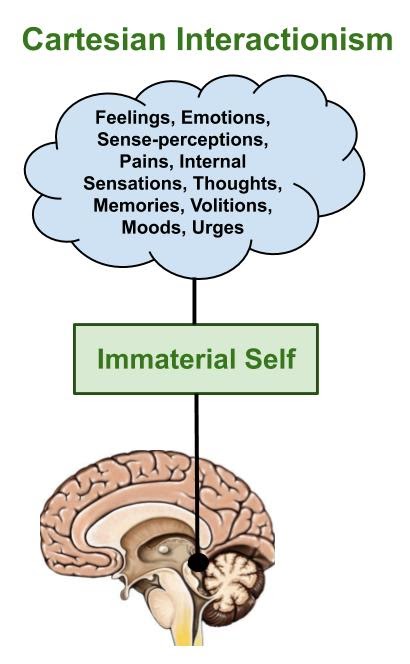

- In the 17th century René Descartes set forth the classic formulation of Interactionism, the view that mind and brain causally interact.

- In 1963 Nobel laureate John Eccles updated the view to accommodate quantum physics and the neural theory of human behavior.

What kind of being must a person be?

- What must a person be in order for Libertarian free will to be possible?

- Two basic views of personhood

- Naturalism: A person is a conscious human organism?

- Substance Dualism: A person is an embodied mind or soul?

- Descartes and Eccles hold the second view.

Cartesian Interactionism

- If human beings have categorical free will they can control whether upper motor neurons fire.

- Descartes explained how this would work:

- A person, who’s an immaterial self, has direct control over their acts of will. A person’s volition to move a part of their body causes changes in the pineal gland which, by the spreading of animal spirits, makes muscles contract and body parts move.

- [Pineal pronounced PIN-ee-ul]

- [The pineal gland, located in the middle of the brain, synthesizes melatonin and appears to have no direct effect on upper motor neurons. ]

Eccles’ Quantum Theory of Control

- In How the Self Controls its Brain, John Eccles proposed a theory like Descartes’ but with an updated mechanism of action.

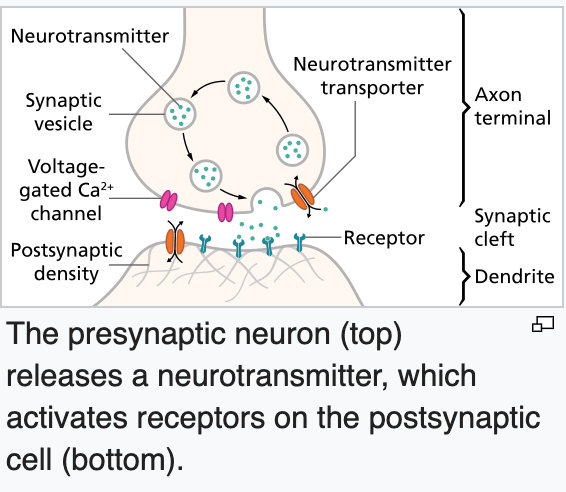

- John Eccles won the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his fundamental work on the synapse.

- Whether a neuron fires depends on the amount and kind of neurotransmitter molecules it receives from its presynaptic neurons.

- Eccles proposed that

- Whether presynaptic neurons release their neurotransmitters is governed by Quantum Physics and is therefore a matter of quantum probabilities.

- “The mental intention (the volition) becomes neurally effective by momentarily increasing the probability of exocytosis in selected cortical areas, such as the supplementary motor area neurons.” (Page 160)

- Exocytosis is the process whereby a presynaptic neuron releases neurotransmitter molecules into the synaptic cleft.

- So, human beings can control whether an upper motor neuron fires by altering the quantum probabilities of quantum brain events that encourage or inhibit the UMN’s firing.

- Eccles feels constrained to “attribute the uniqueness of the self or soul to a supernatural, spiritual creation.” (Page 180)

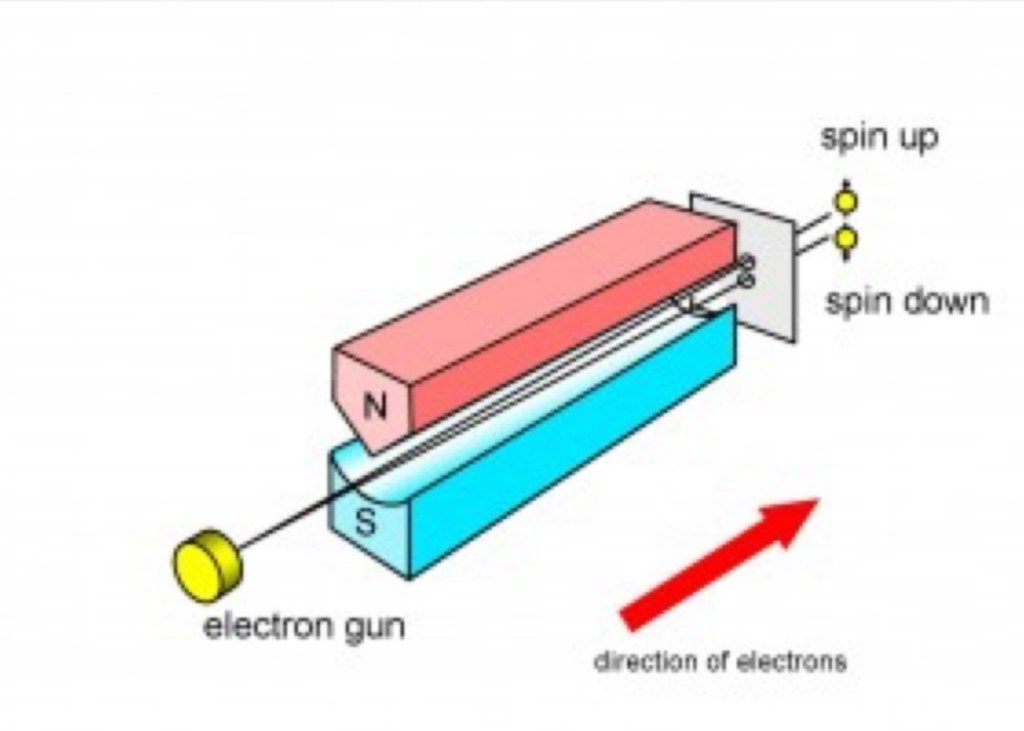

Altering Quantum Probabilities

- The problem with Eccles’ view is that by “altering the probability” of an event, human beings would violate the postulates of Quantum Physics

- In the famous Stern-Gerlach Experiment of the 1920s, a stream of silver atoms is shot through a special magnet. Quantum Mechanics predicts a probability of 0.5 that a given silver atom is deflected upward. The statistical results confirm the prediction.

- Were a person, by telekinesis, able to alter the probability from 0.5 to 0.75, say, which could be confirmed by statistical results, they would refute Quantum Mechanics and violate the laws of nature.

- The same is true of a person altering the quantum probabilities of brain events.

- So the vast evidence supporting Quantum Physics is evidence against Eccles’ theory of free will.

Erwin Schrödinger, from Science and Humanism (1951)

“According to our present view the quantum laws, though they leave the single event undetermined, predict a quite definite statistics of events when the same situation occurs again and again. If these statistics are interfered with by any agent, this agent violates the laws of quantum mechanics just as objectionably as if it interfered —in pre-quantum physics—with a strictly causal mechanical law. … The inference is that … the direct stepping in of free will to fill the gap of indeterminacy … does amount to an interference with the laws of nature, even in their form accepted in quantum theory.”

Arguments for Free Will

Self-Evidence

- The Argument

- “In every act of volition, I am fully conscious that I can at this moment act in either of two ways, and that, all the antecedent phenomena being precisely the same, I may determine one way to-day and another to-morrow.”

- Prolegomena Logica, 1851, Henry Mancel, page 152

- “In every act of volition, I am fully conscious that I can at this moment act in either of two ways, and that, all the antecedent phenomena being precisely the same, I may determine one way to-day and another to-morrow.”

- Mill’s Reply

- John Stuart Mill argued that free will is not the kind of thing that can be self-evident:

- “Consciousness tells me what I do or feel. But what I am able to do, is not a subject of consciousness. Consciousness is not prophetic; we are conscious of what is, not of what will or can be.”

- John Stuart Mill argued that free will is not the kind of thing that can be self-evident:

- What’s self-evident, then, is not that I can act in either of two ways, but that I believe I can.

Moral Responsibility

- The Argument

- People are morally responsible for some of their actions.A person is morally responsible for an action only if they can act otherwise.

- Therefore, people can sometimes act otherwise

- Criticism:

- The argument puts the cart before the horse. Could an addict have refrained on a particular occasion from shooting up? Arguing that the addict was free to refrain because they’re morally responsible begs the question, since the evidence for moral responsibility includes the ability to do otherwise.

Making a Virtue of Necessity

- David Hume and other skeptics argue that there’s no rational foundation for believing in an external world. Yet, they concede they cannot stop believing that physical objects exist. “Nature is always too strong for principle,” as Hume put it.

- Thomas Reid, however, a contemporary of Hume’s, used the inability to give up the belief in an external world as an argument for its rationality.

- “Methinks, therefore, it were better to make a virtue of necessity; and, since we cannot get rid of the vulgar notion and belief of an external world, to reconcile our reason to it as well as we can; for, if Reason should stomach and fret ever so much at this yoke, she cannot throw it off; if she will not be the servant of Common Sense, she must be her slave.”

- Reid’s idea was that belief in the common-sense worldview of physical objects is rational because no rational argument can dislodge it. What’s rational to believe must be believable.

- The same argument can be used for free will:

- What’s rational to believe must be capable of belief.

- Human beings can’t stop believing they have free will

- Hence, it’s irrational to believe there’s no free will.

- The hurdle for this line of argument is explaining how free will is possible in light of the arguments against it:

- Where and how can the chain of neuronal firings diverge?

- Can humans alter quantum probabilities?

View Brain-in-a-vat Argument for Skepticism

Fundamental Mechanisms of Action

Agent Causation

The fundamental mechanism by which a person does something is agent causation, a person directly causing an event such as a volition (Reid) or a brain state (Chisholm 1964).

Roderick Chisholm 1964

- “Human Freedom and the Self” (1964)

- The point is, in a word, that whenever a man does something A, then (by “immanent causation”) he makes a certain cerebral event happen, and this cerebral event (by “transeunt causation”) makes A happen.

- The difference between the man’s causing A, on the one hand, and the event A just happening, on the other, lies in the fact that, in the first case but not the second, the Event A was caused and was caused by the man. There was a brain event A; the agent did, in fact, cause the brain event; but there was nothing that he did to cause it.

Thomas Reid

- Essay IV: Of the Liberty of Moral Agents, Chapter I

- The notions of moral liberty and necessity stated. By the Liberty of a Moral Agent, I understand, a power over the determinations of his own Will. If, in any action, he had power to will what he did, or not to will it, in that action he is free. But if, in every voluntary action, the determination of his will be the necessary consequence of something involuntary in the state of his mind, or of something in his external circumstances, he is not free; he has not what I call the Liberty of a Moral Agent, but is subject to Necessity.

- I consider the determination of the will as an effect. This effect must have a cause which had power to produce it; and the cause must be either the person himself, whose will it is, or some other being. The first is as easily conceived as the last. If the person was the cause of that determination of his own will, he was free in that action, and it is justly imputed to him, whether it be good or bad.

Mental Acts

The fundamental mechanism by which a person does something is the performing of simple mental acts such as decisions and acts of will (volitions, undertakings, endeavorings)

Carl Ginet

- Now, as I explained earlier, if an event is not an action of mine — for example, the door’s opening — then I can make that event occur only by causing it, that is, by performing some action that causes it. But I make my own free, simple mental acts occur, not by causing them, but simply by being their subject, by their being my acts. They are ipso facto determined or controlled by me, provided they are free, that is, not determined by something else, not causally necessitated by antecedent states and events.

Roderick Chisholm 1972

- Person and Object, 1976, Chapter 2 Agency

- Definition D11.5

- S is free at T to undertake P =df there is a period of time which includes, but begins before T, and during which there occurs no sufficient causal condition either for S undertaking P or for S not undertaking P

- Definition D11.6

- P is directly within S is power at T =df there is a Q such that

- S is free at T to undertake Q

- and either

- P = S undertaking Q or

- there occurs an R at T such that it is physically necessary that if R and S-undertaking-Q occur then S-undertaking-Q contributes causally to P

- P is directly within S is power at T =df there is a Q such that

- Definition DII.7

- P is within S’s power at T =df P is a member of a series such that

- the first is directly within S’s power at T and

- each of the others is such that its predecessor in the series is a sufficient causal the condition for its being directly within S’s power

- P is within S’s power at T =df P is a member of a series such that

- Definition D11.5