Gerrymandering is drawing the boundaries of electoral districts to reduce the number of legislative seats an opposing party or targeted voting bloc wins

Outline

- Beware the Gerry-Mander!

- Wasted Votes and the Efficiency Gap

- Cracking and Packing

- Racial and Partisan Gerrymandering

- Census, Apportionment, and Redistricting

- Gerrymandering Links

- Gerrymandering Project gerrymander.princeton.edu

- Gerrymandering in North Carolina

- Rucho v. Common Cause

- States’ Power over Elections

Beware the Gerry-Mander!

A political cartoon of 1812 satirized Governor Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts for redrawing districts, inadvertently making them look like a salamander.

- Gerrymandering is drawing the boundaries of electoral districts to reduce the number of legislative seats an opposing party or targeted voting bloc wins.

- Two things make it possible for state legislatures to gerrymander their congressional districts:

- The proportion of legislative seats a party wins depends not only on the proportion of votes it receives but also on how those votes are distributed across electoral districts.

- The Constitution gives states power over elections, including drawing the boundaries of congressional districts.

- Gerrymandering consists of making the opposing party “waste” more of their votes than the gerrymandering party wastes of theirs.

- A party’s wasted votes are those that were either cast for a losing candidate or, though cast for a winning candidate, were in excess of the number of votes needed to guarantee victory.

- Two gerrymandering techniques:

- Cracking is splitting voters of the opposing party into districts in which they are in the minority, thus making their votes wasted losers.

- Packing is cramming as many voters of the opposing party as possible into the fewest districts, thus making their votes wasted surplus winners.

- Partisan gerrymandering is gerrymandering for the purpose of reducing the number of seats another political party wins.

- In Rucho v. Common Cause, the Supreme Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering is beyond the purview of federal courts.

- Racial gerrymandering is gerrymandering for the purpose of reducing the number of seats a racial minority wins.

- The Voting Rights Act prohibits racial gerrymandering.

Wasted Votes and the Efficiency Gap

- Gerrymandering consists of making the opposing party “waste” more of their votes than the gerrymandering party wastes of theirs.

- Suppose two candidates compete in an election for a single office. The winner gets 60 of the 100 votes cast and the loser 40. Let M be the minimal number of votes guaranteeing victory in an election. Thus M = 51 in an election in which 100 votes are cast. The number of wasted votes in an election is defined as:

- the number of votes cast for the losing candidate + the number of votes cast for the winning candidate – M.

- In the example, the wasted votes consist of:

- the loser’s 40 votes

- the winner’s 9 “surplus” votes

- 60 – 51 = 9

- One party’s distribution of votes is more efficient than another’s if its percentage of wasted votes is less.

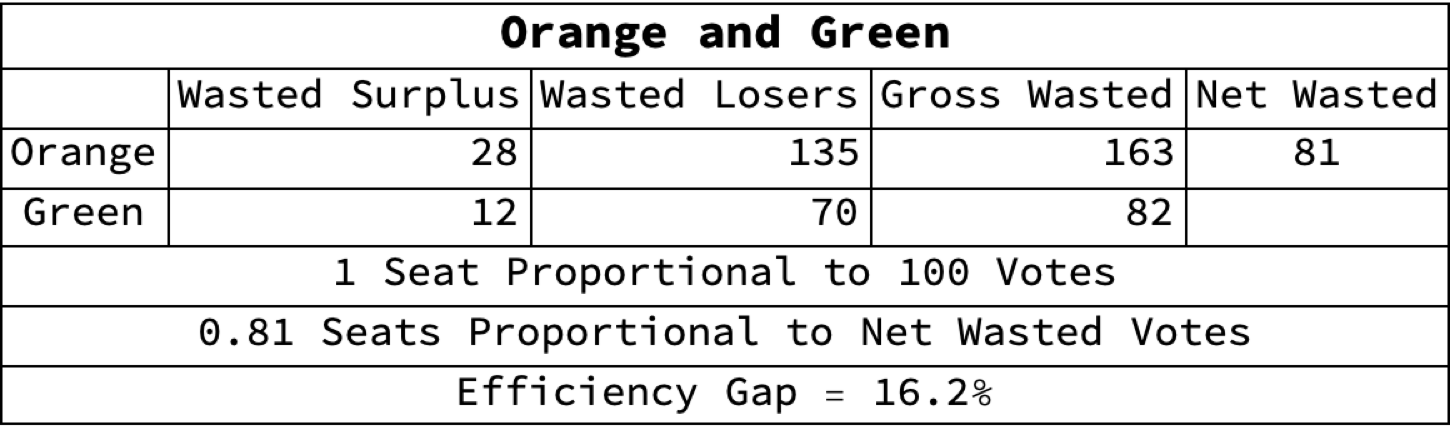

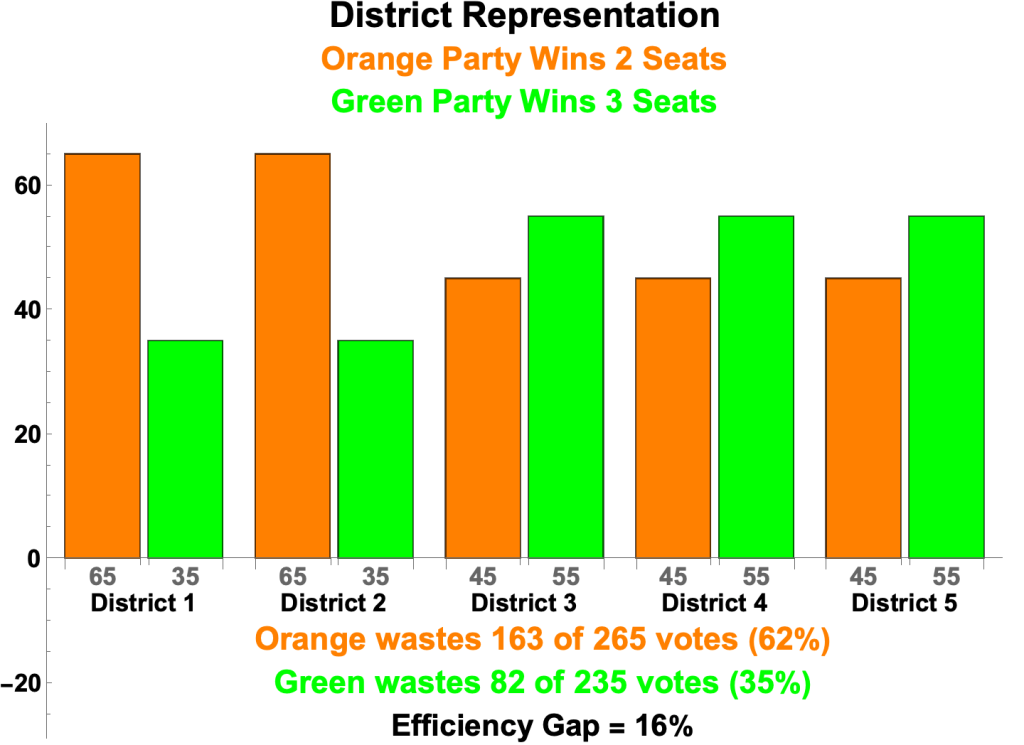

- For example, Orange and Green party voters cast 265 and 235 votes respectively across five 100-member districts as follows:

- Orange wastes 163 votes, consisting of:

- 14 surplus winning votes in each of Districts 1 and 2

- 65 – 51 = 14

- 45 losing votes in each of Districts 3, 4, and 5

- Which totals 14 x 2 + 45 x 3 = 163 wasted votes

- Thus, 62% of Orange’s 265 votes are wasted.

- 14 surplus winning votes in each of Districts 1 and 2

- Green wastes 82 votes, consisting of:

- 35 losing votes in each of Districts 1 and 2

- 4 surplus winning votes in each of Districts 3, 4, and 5

- 55 – 51 = 4

- Which totals 35 x 2 + 4 x 3 = 82 wasted votes

- Thus 35% of Green’s 235 votes are wasted.

- The distribution of Green’s votes across districts is thus more efficient than Orange’s.

- The number of wasted votes can be translated into the number of seats lost due to wasted votes. The translation goes like this:

- 1 seat is proportional to 100 votes

- Votes per seat = 500 votes / 5 seats = 100

- Orange wasted 81 more votes than Green

- Orange’s net wasted votes = Orange’s wasted votes – Green’s wasted votes = 163 – 82 = 81

- Therefore, Orange lost 0.81 seats because of wasted votes.

- 81 / 100 = 0.81

- 1 seat is proportional to 100 votes

- A useful notion in assessing the role of wasted votes in an election is the Efficiency Gap, developed by Nicholas Stephanopoulos and Eric McGhee:

- Efficiency Gap = (the number of one party’s wasted votes − the number of the other party’s wasted votes) / the total votes cast.

- The Efficiency Gap between Orange and Green is thus (163 – 82) / 500 = 16.2%

- The Efficiency Gap provides:

- a single number that characterizes the difference between parties’ wasted votes

- a quick way to translate wasted votes into lost seats

- Lost seats = the number of seats x the efficiency gap

- 0.81 = 5 x 0.162

- Lost seats = the number of seats x the efficiency gap

- Here’s a summary:

Cracking and Packing

- A party gerrymanders districts by making the opposing party or voting bloc waste more of their votes than the gerrymandering party wastes of theirs. There are two methods:

- Cracking is splitting voters of the opposing party into districts in which they are in the minority, making their votes wasted losers.

- Packing is cramming as many voters of the opposing party as possible into the fewest districts, making their votes wasted surplus winners.

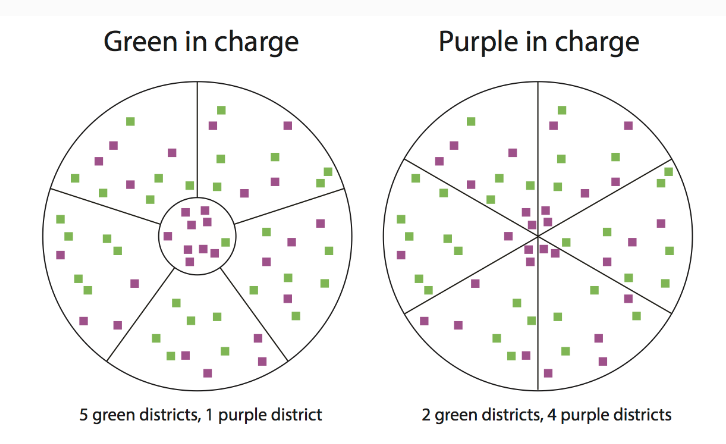

First Example, from the Gerrymandering Project

- Each circle consists of 60 voters

- 31 members of the Green Party

- 29 members of the Purple Party

- Green draws the district boundaries of the Left Circle.

- Purple draws the boundaries of the Right Circle.

- Rules:

- You can’t move the dots (the people).

- You have to form six districts, each with 10 people.

- The districts must partition the entire circle.

- The districts must be contiguous, i.e. a person can travel from any point in the district to any other point without having to cross a different district.

- Green’s gerrymandering (left circle):

- Green packs 9 purple votes into the center ring and cracks Purple’s remaining 20 votes by splitting them into the 5 outer districts where Green wins each 6 to 4.

- Result:

- Green wins the 5 outer districts 6 to 4.

- Purple wins the center district 9 to 1.

- Purple’s gerrymandering (right circle):

- Purple cracks 16 Green votes into 4 districts (top left, top right, bottom left, bottom right) so that Purple beats Green in those districts by small margins.

- Purple packs Green’s 15 remaining votes into 2 districts (center left, center right) so that Green beats Purple in those districts by large margins.

- Result:

- Purple wins the top left, top right, bottom left, and bottom right sectors 6 to 4.

- Green wins the left center sector 8 to 2 and the right center sector 7 to 3.

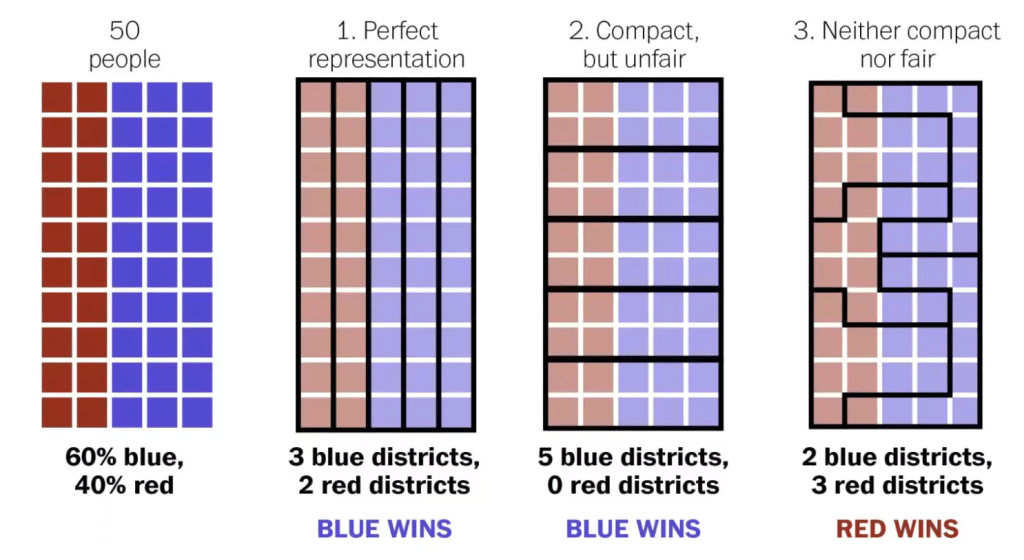

Second Example, from the Washington Post

- This is the Best Explanation of Gerrymandering You Will Ever See, Christopher Ingraham, WaPo

- Scenario

- 50 voters: 30 blue and 20 red

- 5 districts of 10 members each

- Rules: Every district must be contiguous and have the same number of voters, 10.

- Grid #2: Blue’s Gerrymander

- Blue cracks Red’s 20 votes into five districts in which Blue wins each by 2 votes.

- Result

- Blue wins all five districts 6 to 4

- Grid #3: Red’s Gerrymander

- Red cracks 12 Blue votes into 3 districts (facing left) so that Red wins each by 2 votes.

- Red packs Blue’s remaining 18 votes into 2 districts (facing right) so that Blue wins each 9 to 1.

- Result

- Red wins 3 districts 6 to 4

- Blue wins 2 districts 9 to 1

Racial and Partisan Gerrymandering

- Gerrymandering is drawing electoral boundaries to reduce the number of legislative seats an opposing party or targeted voting bloc wins

- In 1986 the Supreme Court ruled that racial gerrymandering, where the targeted group is a racial or ethnic minority, is unconstitutional.

- In 2019 the Supreme Court ruled that claims of partisan gerrymandering, where the targeted group is a political party, are political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.

Census, Apportionment, and Redistricting

- The US Census is taken every ten years (next census 2030)

- Congressional Apportionment is the process by which seats in the House of Representatives are distributed among the 50 states according to the census.

- Congressional Redistricting is the process whereby states determine voting districts based on

- Census data

- Number of House seats

- One person one vote rule

- In Baker v. Carr (1962) the Supreme Court instituted the one person, one vote rule that, under the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution, legislative voting districts must be the same in population size.

- Voting Rights Act of 1965

- Prohibits plans that intentionally or inadvertently discriminate on the basis of race, which could dilute the minority vote.

- State legislatures redraw voting districts in 28 states. Other states use commissions

Gerrymandering Links

- Princeton Gerrymandering Project

- Partisan Gerrymandering and the Efficiency Gap, University of Chicago Law Review, 2015

- Alternative Link: papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2457468

- How the Efficiency Gap Works, Brookings Institute

- Efficiency Gap, Wikipedia

- How the Supreme Court could limit gerrymandering, explained with a simple diagram , Alvin Chang, Vox

Gerrymandering Project

gerrymander.princeton.edu

“The Gerrymandering Project does nonpartisan analysis to understand and eliminate partisan gerrymandering at a state-by-state level.”

Gerrymandering in North Carolina

- How to spot an unconstitutionally partisan gerrymander, explained, Vox

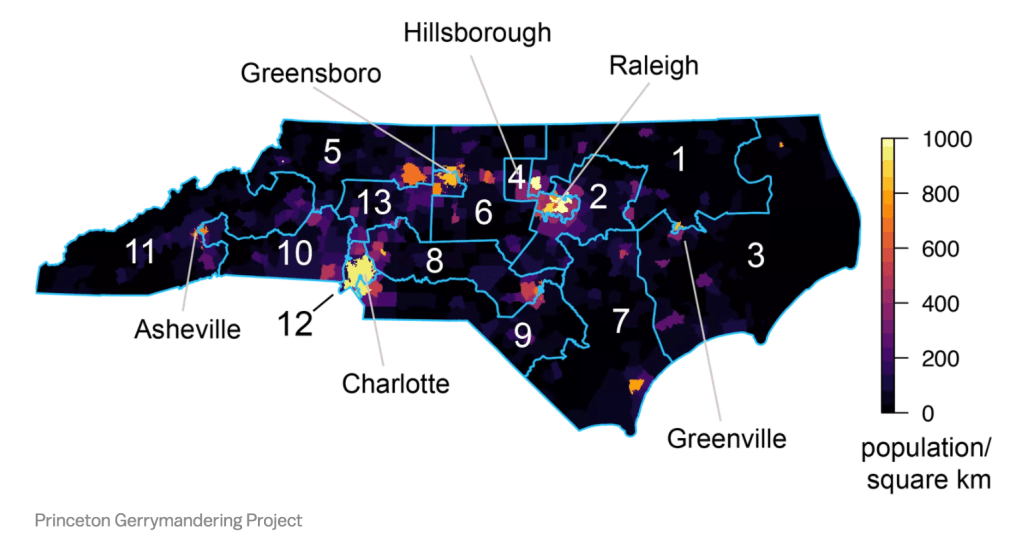

- Communities, like Raleigh and Hillsborough, were packed together in the Fourth District to concentrate Democratic voters, while other communities, like Greenville, Asheville, and Greensboro, were cracked between several districts to dilute their voting power.

George Holding (R) won the 2nd District with 57% of the vote in 2016. The district snakes around the 4th District to the east. Essentially the entire city of Raleigh is packed away into the heavily Democratic 4th District, which David E. Price (D) won with a commanding 68% of the vote.

Republicans drew the border between the 13th District and 6th District through the middle of the Greensboro, a Democratic stronghold, effectively splitting the Democratic population in two and ensuring that Democrats would have difficulty competing in either district.

Rucho v. Common Cause

The Case

- Plaintiffs in North Carolina and Maryland filed suits challenging their States’ congressional districting maps as unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders, alleging violations of the First Amendment, the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Elections Clause, and Article I, §2

- Chief Justice Roberts delivered the opinion of the Court, joined by Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh. Kagan filed a dissenting opinion, joined by Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor.

- Decided June 27, 2019

- Holding

- Partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts. Such claims are not justiciable.

- Justiciable (jus-TISH-a-bull) = capable of being decided by legal principles or by a court of justice

- Partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts. Such claims are not justiciable.

- oyez.org/cases/2018/18-422

- law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/18-422

NY Times Interactive on Gerrymandering in North Carolina (NYT)

John Roberts for the Majority

- We conclude that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts. Federal judges have no license to reallocate political power between the two major political parties, with no plausible grant of authority in the Constitution, and no legal standards to limit and direct their decisions. (page 30)

- To hold that legislators cannot take their partisan interests into account when drawing district lines would essentially countermand the Framers’ decision to entrust districting to political entities. (page 2, 12)

- The “central problem” is “determining when political gerrymandering has gone too far.” (page 2,13)

- … the Constitution does not require proportional representation, and federal courts are neither equipped nor authorized to apportion political power as a matter of fairness. It is not even clear what fairness looks like in this context. It may mean achieving a greater number of competitive districts by undoing packing and cracking so that supporters of the disadvantaged party have a better shot at electing their preferred candidates. But it could mean engaging in cracking and packing to ensure each party its “appropriate” share of “safe” seats. Or perhaps it should be measured by adherence to “traditional” districting criteria. Deciding among those different visions of fairness poses basic questions that are political, not legal. There are no legal standards discernible in the Constitution for making such judgments. And it is only after determining how to define fairness that one can even begin to answer the determinative question: “How much is too much?” (page 3)

- The fact that the Court can adjudicate one-person, one-vote claims does not mean that partisan gerrymandering claims are justiciable. This Court’s one-person, one-vote cases recognize that each person is entitled to an equal say in the election of representatives. It hardly follows from that principle that a person is entitled to have his political party achieve representation commensurate to its share of statewide support. Vote dilution in the one-person, one-vote cases refers to the idea that each vote must carry equal weight. That requirement does not extend to political parties; it does not mean that each party must be influential in proportion to the number of its supporters. The racial gerrymandering cases are also inapposite: They call for the elimination of a racial classification, but a partisan gerrymandering claim cannot ask for the elimination of partisanship. Pp. 15–21. (page 3)

- Excessive partisanship in districting leads to results that reasonably seem unjust. But the fact that such gerrymandering is “incompatible with democratic principles,” Arizona State Legislature, 576 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 1), does not mean that the solution lies with the federal judiciary. (page 30)

- But the history of partisan gerrymandering is not irrelevant. Aware of electoral districting problems, the Framers chose a characteristic approach, assigning the issue to the state legislatures, expressly checked and balanced by the Federal Congress, with no suggestion that the federal courts had a role to play. (page 2)

- The Framers also gave Congress the power to do something about partisan gerrymandering in the Elections Clause. That avenue for reform established by the Framers, and used by Congress in the past, remains open. Pp. 30–34. (page 5)

Elena Kagan for the Minority

- Partisan gerrymandering …

- …subverts democracy (page 8)

- The “core principle of republican government,” this Court has recognized, is “that the voters should choose their representatives, not the other way around.”

- …implicates the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause (page 11)

- The Fourteenth Amendment, we long ago recognized, “guarantees the opportunity for equal participation by all voters in the election” of legislators.

- …implicates the First Amendment (page 12)

- That Amendment gives its greatest protection to political beliefs, speech, and association. Yet partisan gerrymanders subject certain voters to “disfavored treatment”—again, counting their votes for less—precisely because of “their voting history [and] their expression of political views.”

- …subverts democracy (page 8)

- A workable test for evaluating a vote dilution claim has three parts: (1) intent; (2) effects; and (3) causation. (page 16)

Roberts’ Arguments, Reconstructed

- Drawing district lines is a political rather than a legal matter because the Framers entrusted districting to political entities.

- Article 1, Section 4

- The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof

- Article 1, Section 4

- Neither the Constitution nor legal standards justifies the judiciary reallocating political power (even in the interest of fairness).

- Therefore, neither the Constitution nor legal standards justifies the judiciary drawing district lines (even in the interest of fairness).

- This Court’s one-person, one-vote cases recognize that each person is entitled to an equal say in the election of representatives. It doesn’t follow from this that each person is entitled to have his political party achieve representation commensurate to its share of statewide support.

- There’s no workable test for determining whether a redistricting plan is unfair. So there’s no way for a court to decide such matters.

Kagan’s Argument, Reconstructed

- Partisan gerrymandering violates

- The core principle of republican government

- The Court has recognized “that the voters should choose their representatives, not the other way around.”

- Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause

- The Fourteenth Amendment, we long ago recognized, “guarantees the opportunity for equal participation by all voters in the election” of legislators.

- First Amendment

- That Amendment gives its greatest protection to political beliefs, speech, and association. Yet partisan gerrymanders subject certain voters to “disfavored treatment”—again, counting their votes for less—precisely because of “their voting history [and] their expression of political views.”

- The core principle of republican government

- Therefore, partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional.

- Standards adopted in lower courts do indeed meet the contours of the “limited and precise standard” the majority demanded yet purported not to find.

- A workable test for evaluating a vote dilution claim is based on intent, effects, and causation.

States’ Power over Elections

States’ powers over elections derive from ArtIcle 1, Section IV, Clause 1 of the Constitution

- “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators.”

States’ Powers

States decide who the “people” are

- States decide who the “people” are, i.e. who can vote (within the constraints imposed by the Constitution and federal law).

- Constitutional amendments and federal law have put constraints on states’ power to decide who can vote.

States decide procedures for determining an election’s outcome

- Systems for determining the outcome of an election: A candidate wins if they get:

- A plurality of votes

- A majority of votes, using either

- ranked choice voting (instant runoff)

- or

- possible runoff election

- ranked choice voting (instant runoff)

- A supermajority of votes

- A unanimity of votes

- Georgia, Louisiana, and Maine elect officials by majority

- Georgia and Louisiana conduct runoff elections if needed

- Maine uses Instant Runoff Voting (Ranked Choice Voting)

States draw boundaries of congressional districts

- In Rucho v. Common Cause the Supreme Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering does not violate the Constitution.