Why people believe irrational things

Contents

- Rational Way to Determine What’s True

- Believing What You’re Disposed to Believe

- Confirmation Bias

- The Problem with Believing by Motivated Reasoning

- Examples of Motivated Reasoning Leading to False Beliefs

- Predispositions to Believe

- Defense Mechanisms for Protecting Core Beliefs

- Addendum

Rational Way to Determine What’s True

- Suppose a question arises, for example:

- Whether Biden was legitimately elected president;

- Whether Thomas Jefferson fathered some of Sally Hemings children;

- Whether Vitamin C helps prevents colds;

- Whether “facilitated communication” works.

- A rational approach to answering such questions is something like this:

- Gather evidence for and against the proposition at issue.

- Evaluate the evidence.

- Determine the probability of the proposition based on the totality of evidence, thus determining whether the proposition is beyond a reasonable doubt, very likely, more probable than not, doubtful, very likely false, and so on.

- Such an approach is time-consuming and labor-intensive. So people take shortcuts.

- One shortcut is to rely on other people’s opinions.

- Another is to believe what you’re disposed to believe, regardless of the evidence.

Believing What You’re Disposed to Believe

- But how does a person believe what they’re inclined to believe, e.g. that Biden’s 2020 victory was not legitimate?

- What’s the psychological mechanism?

Belief is Not in a Person’s Direct Control

- You might think that a person can come to believe what they’re predisposed to believe by simply willing to believe it — in the same way a person can bend their index finger by merely willing it to bend.

- When you bend your finger, you just bend it. That’s it. You don’t have to bend it by doing something else, like bending it with your other hand.

- But people can’t believe something merely by willing to believe it. Belief is not in a person’s direct control.

- “Many philosophers and psychologists have concluded that belief is a more or less involuntary response to perceived evidence.”

- “Belief is not subject to the will. Men think as they must.”

- Robert Ingersoll, Why I Am An Agnostic (1889)

- For example, you can’t simply will to believe there’s a live rattlesnake under the couch. You can make yourself believe it — but only indirectly, by doing something that causes the belief, for example, getting a rattlesnake, letting it loose in the room, and watching it slither under the couch. Only then do you believe there’s a rattlesnake under the couch. Indeed, once you see the snake, you can’t help but believe it.

- Belief is not under a person’s direct control like bending your finger. Rather, beliefs form automatically, typically as a response to acquiring reasons for the belief.

- When you see a snake slithering across the floor you automatically believe there’s a snake in the room. The reason for your belief is that you see the snake.

Motivated Reasoning

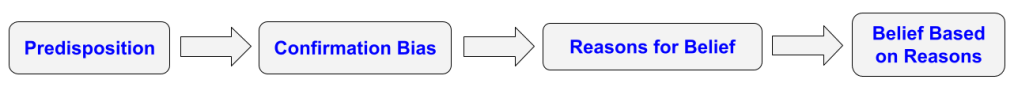

- A person can come to believe what they are predisposed to believe through motivated reasoning.

- Here’s how it works.

- A person — call him Sam — is predisposed to believe that X is true, i.e. disposed to believe X before having evidence.

- The predisposition leads Sam to:

- look for, recognize, and accept reasons for believing X and

- avoid, ignore, and dismiss, reasons against believing X.

- This is confirmation bias.

- In this way Sam comes to have reasons for believing X.

- As a result, Sam comes to believe X based on those reasons.

Motivated Reasoning, by Ziva Kunda

- In a highly cited 1990 paper The Case for Motivated Reasoning, Ziva Kunda wrote:

- “People do not seem to be at liberty to conclude whatever they want to conclude merely because they want to. Rather, I propose that people motivated to arrive at a particular conclusion attempt to be rational and to construct a justification of their desired conclusion that would persuade a dispassionate observer. They draw the desired conclusion only if they can muster up the evidence necessary to support it. In other words, they maintain an ‘illusion of objectivity’.”

Motivated Brain Hypothesis, by Sander van Linden

- From Sander van Linden’s 2023 book Foolproof: Why Misinformation Infects Our Minds and How to Build Immunity

- The essential idea [of the Motivated Brain Hypothesis] is that our basic cognitive processes–including our memory, perception, attention, and especially our judgments–are colored by our own motivations. Rather than just seeing the evidence for what it is, you can think of it as strong top-down interference. Your brain is filling in the gaps for you based on what you would like to be true.

Confirmation Bias

- Confirmation Bias is the disposition to:

- look for, recognize, accept, and remember reasons for believing a proposition and

- avoid, ignore, dismiss, and forget reasons against believing it.

- Francis Bacon in 1620:

- “The human understanding when it has once adopted an opinion draws all things else to support and agree with it. And though there be a greater number and weight of instances to be found on the other side, yet these it either neglects and despises, or else by some distinction sets aside and rejects; in order that by this great and pernicious predetermination the authority of its former conclusions may remain inviolate….It is the peculiar and perpetual error of the human intellect to be more moved and excited by affirmatives than by negatives.” (Novum Organum, XLVI, page 23)

- Link to Britannica on Confirmation Bias

The Problem with Believing by Motivated Reasoning

- The problem with believing by motivated reasoning is that, because of confirmation bias, the belief is based only on a subset of the total evidence, a subset that supports the belief. Believing by motivated reasoning thus runs the real risk of resulting in a false belief.

Examples of Motivated Reasoning Leading to False Beliefs

WMD’s in Iraq

- The 2002 US National Intelligence Estimate judged that

- “Iraq has continued its weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programs in defiance of UN resolutions and restrictions.”

- But no WMDs were found.

- In 2004 the Select Senate Committee on Intelligence concluded that

- “Most of the major key judgments in the … 2002 National Intelligence Estimate … either overstated, or were not supported by, the underlying intelligence reporting.”

- The report noted that the Intelligence Community (IC) was predisposed to believe that Iraq had WMDs.

- “The fact that Iraq had repeatedly lied about its pre-1991 WMD programs, its continued deceptive behavior, and its failure to fully cooperate with UN inspectors left the IC with a predisposition to believe the Iraqis were continuing to lie about their WMD efforts.”

- The predisposition led to Confirmation Bias.

- “The Intelligence Community (IC) suffered from a collective presumption that Iraq had an active and growing weapons of mass destruction (WMD) program. This “groupthink” dynamic led Intelligence Community analysts, collectors and managers to both interpret ambiguous evidence as conclusively indicative of a WMD program as well as ignore or minimize evidence that Iraq did not have active and expanding weapons of mass destruction programs.”

- A particular example:

- “Another example of the IC’s tendency to reject information that contradicted the presumption that Iran had active and expanded WMD programs was the return of UN inspectors to Iraq in Nov 2002. When these inspectors did not find evidence of active Iraqi WMD programs and, in fact, even refuted some aspects of the IC’s nuclear and biological assessments, many analysts did not regard this information as significant. For example, the 2002 NIE cited Iraq’s Amiriyah Serum and Vaccine Institute as reasons the IC believed the facility was a “fixed dual-use BW agent production” facility. When UN inspectors visited Amiriyah after their return to Iraq in November 2002, however, they did not find any evidence of BW work at the facility. Analysts discounted the UN’s findings as the result of the inspectors relative inexperience in the face of Iraqi denial and deception.”

Facilitated Communication

Image Source ScienceNordic

- Facilitated communication is the now-debunked technique for enabling an autistic or non-verbal person to communicate by typing on a keyboard, aided by a facilitator.

- Before it was debunked, facilitators believed that they were merely helping autistic children type what they — the children — were trying to type. In the early 1990s a simple experiment showed that it was the facilitator, not the child, who was the source of messages displayed on the output screen.

- View Test of FC

- Facilitators believed that FC worked because

- they were predisposed to believe it worked since they had an emotional stake in it working

- the predisposition prevented them from realizing that they were the ones actually controlling the input device

- their predisposition was supported by the fact that other facilitators also thought FC worked

- there was no outright disproof of FC (before it was debunked).

Predispositions to Believe

Wishful Believing

- Perhaps the most common predisposition is the inclination to believe what you want to be true, what you have an emotional stake in believing.

- Francis Bacon, 1620

- “The human understanding is no dry light, but receives an infusion from the will and affections; whence proceed sciences which may be called ‘sciences as one would.’ For what a man had rather were true he more readily believes.” (Novum Organum, XLIX, page 26, year 1620).

- Examples

- People are predisposed to believe there’s an afterlife because they want their mental lives, and those of their loved ones, to continue after they die.

- Facilitators and parents of autistic children were predisposed to believe that facilitated communication worked because they had an emotional stake in its being real.

Group Belief

- Another common predisposition is the inclination to believe what members of a group you identify with believe. As social psychologist Sander van Linden puts it in his book Foolproof: Why Misinformation Infects Our Minds and How to Build Immunity:

- “Sometimes we willingly distort our perception of the evidence for social purposes because we have a deep need to belong and identify with like-minded others.”

- In the Iraq WMD example, the predisposition to believe that Iraq had WMDs was a “collective presumption” — a “groupthink dynamic” that led to confirmation bias.

- In the facilitated communication example, the predisposition to believe that FC worked was shared by facilitators and parents.

Defense Mechanisms for Protecting Core Beliefs

- People adopt various mechanisms for protecting their deeply-held beliefs from evidence contradicting them. The mechanisms prevent or relieve “cognitive dissonance.”

Cognitive Dissonance

- Britannica on Cognitive Dissonance

- Cognitive Dissonance is the mental conflict that occurs when beliefs or assumptions are contradicted by new information. The unease or tension that the conflict arouses in people is relieved by one of several defensive maneuvers:

- they reject, explain away, or avoid the new information;

- they persuade themselves that no conflict really exists

- they reconcile the differences;

- or they resort to any other defensive means of preserving stability or order in their conceptions of the world and of themselves.

- The concept was developed in the 1950s by American psychologist Leon Festinger and became a major point of discussion and research.

- Cognitive Dissonance is the mental conflict that occurs when beliefs or assumptions are contradicted by new information. The unease or tension that the conflict arouses in people is relieved by one of several defensive maneuvers:

Defense Mechanisms

- How to protect a core belief against counter-evidence:

- Reject Counter-Evidence

- Argue that the core belief casts doubt on the counter-evidence rather than the other way around.

- Put forth an Ad Hoc Hypothesis

- Put forth an hypothesis that explains how the “counter-evidence” is in fact logically compatible with the core belief.

- Appeal to Religious Faith

- Argue that the core belief constitutes a commitment to a way of life rather than a hypothesis to be assessed by the evidence.

- Live in an Epistemic Bubble

- Avoid counter-evidence altogether by using sources of information that support your core beliefs and avoid those that can threaten them.

- Reject Counter-Evidence

Reject Counter-Evidence

- To protect a core belief against counter-evidence, a person may argue that the belief casts doubt on the counter-evidence rather than the other way around.

- For example, to protect their belief that the Bible is the word of God, fundamentalists argue that the creation story in Genesis proves that the theory of evolution is false.

Put Forth an Ad Hoc Hypothesis

- To protect a core belief against counter-evidence, a person may put forth an “ad hoc” hypothesis that explains how the “counter-evidence” is in fact logically compatible with the belief.

- Ad hoc means for the specific purpose, case, or situation at hand and for no other (American Heritage Dictionary).

- The classic example of an ad hoc hypothesis is a psychic who, confronted with the negative results of a test of his abilities, claims the experimenter’s skeptical attitude disrupted his psychic powers. The example involves:

- the psychic’s core belief that he has psychic powers

- the contrary evidence that psychic failed the test of his powers

- the ad hoc hypothesis that the experimenter’s attitude disrupted the psychic’s special powers.

- For a second example see Doug Biklen’s Ad Hoc Hypothesis

Appeal to Religious Faith

- To protect a core belief against contrary evidence, a believer may argue that argue that the belief constitutes a commitment to a way of life rather than a hypothesis to be assessed by evidence.

- Theists typically subscribe to Fideism, the view that religious truths are ultimately based on faith rather than on reason and evidence.

- Faith protects religious beliefs by removing them from the realm of hypothesis, evidence, and reason. Such beliefs are regarded, not as hypotheses, but as comprising a worldview and approach to life that rest on faith and commitment rather than reason and evidence. Skeptical doubts are viewed as attacks on a chosen way of life rather than as evidence casting doubt on a hypothesis.

Live in an Epistemic Bubble

- To protect core beliefs against contrary evidence, a person can avoid counter-evidence altogether by using sources of information that reinforce core beliefs and avoid sources that may threaten them.

- Sources of information include people, clubs, organizations, groups, news outlets, books, movies, schools, courses, radio and television programs, websites, and social media.

Addendum

- “Predispose”

- Honest and Motivated Mistakes

- Motivated Numeracy and Enlightened Self-Government

- Foolproof: Why Misinformation Infects Our Minds and How to Build Immunity

- Charismatic Authority

“Predispose”

- merriam-webster.com/thesaurus/predispose

- How is the word predispose different from other verbs like it?

- Some common synonyms of predispose are bias, dispose, and incline. While all these words mean “to influence one to have or take an attitude toward something,” predispose implies the operation of a disposing influence well in advance of the opportunity to manifest itself.

Honest and Motivated Mistakes

- Irrational beliefs result from either “honest” or “motivated” mistakes.

- An irrational belief typically results from making an “honest mistake,” A person motivated to find the truth forms an irrational belief because of an unintentional epistemic error, such as:

- misinterpreting what they see, hear, or read,

- confusing one thing with another,

- getting information from unreliable sources,

- being fooled by statistics.

- But an irrational belief may also result from a “motivated mistake.” A person forms an irrational belief based on epistemic errors that result from their predisposition to believe one thing rather than another.

Motivated Numeracy and Enlightened Self-Government

- In their study reported in Motivated Numeracy and Enlightened Self-Government, Dan Kahan and others set out to answer the question whether “Ideologically motivated cognition” has more effect on less numerate individuals in interpreting quantitative data than on those who are more number savvy.

- The subjects, comprised of Liberal Democrats and Conservative Republicans, were given a battery of tests to determine their numeracy (graded 0 through 9), that is, their ability and disposition to assess quantitative information.

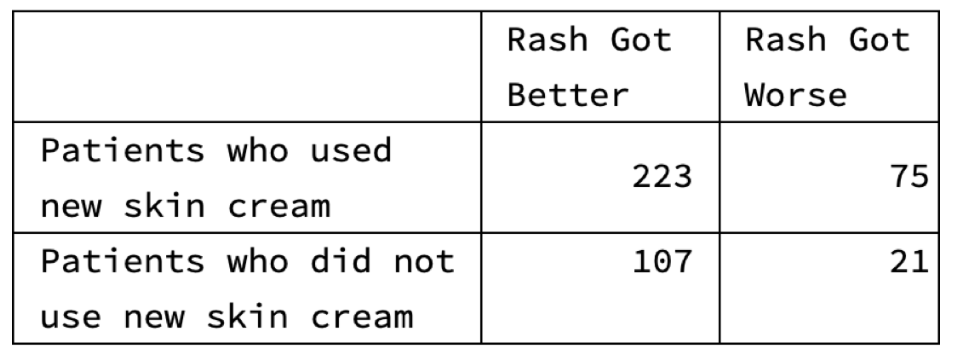

- A subset of the subjects were shown the results of a (fake) study on the effectiveness of a new skin cream:

- They were then asked which conclusion the results supported:

- A: People who used the skin cream were more likely to get better than those who didn’t.

- B: People who used the skin cream were more likely to get worse than those who didn’t.

- The more numerate subjects did better than the others. There was no significant difference between Democrats and Republicans.

- The rational answer was that the results supported the conclusion that the skin cream was likely to make the rash worse because the rash got worse for 25 percent of those using the skin cream, compared to 16 percent of those not using the skin cream.

- A bad answer: the results supported the conclusion that the skin cream was likely to make the rash better because the rash got better for a lot more people using the skin cream than for those who didn’t.

- Another bad answer: the results supported the conclusion that the skin cream was likely to make the rash better because the only results that matter are for those using the skin cream.

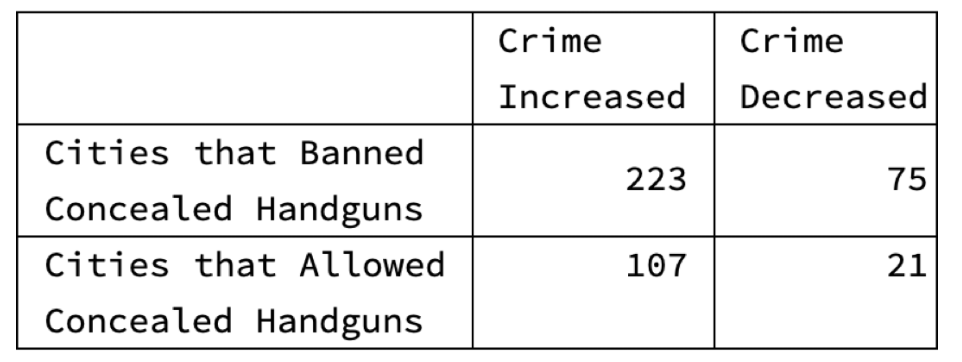

- Another subset of the subjects were shown the results of a (fake) study on the effectiveness of banning concealed handguns (using the same figures as the skin cream experiment):

- They were then asked which conclusion the results supported:

- A. Cities that enacted a ban on carrying concealed handguns were more likely to have a decrease in crime than cities without bans.

- B. Cities that enacted a ban on carrying concealed handguns were more likely to have an increase in crime than cities without bans.

- The more numerate Republicans did much better than their less numerate counterparts, as they had on the skin cream question. But the more numerate Democrats did no better than less numerate Democrats and did significantly worse than the more numerate Republicans. (On other versions of the test numerate Democrats did better than numerate Republicans.)

- The conclusion of the study was thus that ideologically motivated cognition can affect anyone in interpreting quantitative data, no matter their degree of numeracy.

Foolproof: Why Misinformation Infects Our Minds and How to Build Immunity, 2023, Sander van Linden

- CHAPTER 2 The motivated brain: What you want to believe

- The Bayesian Brain Hypothesis

- If the brain were optimally attuned to processing evidence, many of us think the brain would be ‘Bayesian’. Bayes’s theorem was named after the eighteenth-century English mathematician Reverend Thomas Bayes and his work on conditional probabilities. In its simplest form, Bayes’s rule can be thought of as a formula for how to update probabilities that certain hypotheses we might have about the world are true, given the available evidence. In other words, you might have established some prior beliefs about an event (for example, that NASA faked the moon landing). You then encounter a piece of evidence–such as a statistic or fact–which strongly contradicts this belief (such as the 300 kilos of verified moon rock that the astronauts brought back). Following a Bayesian approach, you would update your new (formally called ‘posterior’) belief in accordance with this evidence.

- Motivated Brain Hypothesis

- The essential idea [of the Motivated Brain Hypothesis] is that our basic cognitive processes–including our memory, perception, attention, and especially our judgments–are colored by our own motivations. Rather than just seeing the evidence for what it is, you can think of it as strong top-down interference. Your brain is filling in the gaps for you based on what you would like to be true. Why do you choose to read one news article but not another? Unlike low-level perception, in which the brain is trying to lend a hand but sometimes fails (think of the optical illusion), the motivated brain selectively and often consciously seeks out or rejects evidence in a way that supports what you already believe.

- One basic guiding motivation is the desire to be acquainted with the facts–to be accurate. Everyone has the capability to be motivated by accuracy: we just want to know the truth, discover how something really works, or uncover the best available evidence on a topic. What psychologists call ‘accuracy motivation’ is a fundamental force that drives much of human cognition. We can all think of a time when we used all of our mental resources to find out the ‘cold hard truth’.

- Some situations decrease ‘accuracy motivation’ in favor of other kinds of motivations. Yet, these other motivations do not always need to be political or deliberately malevolent or nefarious. Sometimes we willingly distort our perception of the evidence for social purposes because we have a deep need to belong and identify with like-minded others. This can often be a far more powerful and adaptive motivation to navigate the world. In fact, one key insight from social psychology is that we derive part of our identities from the groups that we belong to. Thus, we often need to balance social motivations–such as the need to fit in–against our desire for accuracy.

Charismatic Authority

- For the German sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920), a person has charismatic authority over a group if its members regard him or her as having extraordinary abilities and knowledge. As the Britannica puts it, “the charismatic leader can demand and receive complete devotion from his or her followers. The foundation of charismatic authority is emotional, not rational: it rests on trust and faith, both of which can be blind and uncritical. Unrestrained by custom, rules, or precedent, the charismatic leader can demand and receive unlimited power.”

- Example of Heaven’s Gate

- In 1997 thirty-nine followers of Marshall Applewhite, 21 women and 18 men between the ages of 26 and 72, committed suicide in the belief that they would be transported to a spaceship where they would attain “The Evolutionary Level Above Human”.