Back to Special Relativity

Contents

- Relativistic Mechanics

- Relativistic Quantum Mechanics

- Kinetic Energy in Classical and Relativistic Mechanics

Classical Mechanics and Quantum Mechanics presuppose that distances and intervals are the same across inertial reference frames. The theories had to be modified to make them compatible with Special Relativity. (Maxwell’s Theory of Electromagnetism required no modification.)

Relativistic Mechanics

- Momentum

- p = mv in Classical Mechanics is replaced by p = γmv in Relativistic Mechanics, where γ is the Lorentz Factor 1/√(1 – v2/c2).

- Equation of Motion

- F = ma is replaced by F = dp/dt, where p is momentum

- Kinetic Energy

- K = ½ mv2 is replaced by K = γmc2, where γ is the Lorentz Factor 1/√(1 – v2/c2).

Relativistic Quantum Mechanics

- In 1928 Paul A.M. Dirac set forth a wave equation for the electron that combined Special Relativity with Quantum Mechanics

- The theory explained the spin of the electron that had been earlier theorized.

- It also predicted antimatter.

- “From the beginning, Dirac was aware that his theory had a problem: it had an extra set of solutions that made no physical sense, as they corresponded to negative values of energy. After failing to make sense of this negative energy, Dirac admitted in 1931 that his theory, if true, implied the existence of “a new kind of particle, unknown to experimental physics, having the same mass and opposite charge to an electron.” One year later, to the astonishment of physicists, this particle—the antielectron, or positron—was accidentally discovered in cosmic rays by Carl Anderson of the United States.”

Kinetic Energy in Classical and Relativistic Mechanics

Derivation of Kinetic Energy from Momentum

- KE = ∫ F dx

- KE = the kinetic energy of a particle = the quantity of work required to increase the velocity of the particle from zero to v

- Work = force x distance (F dx)

- ∫ F dx = the integral of F dx, that is, (very) roughly, the sum of the force F times each tiny piece of distance.

- KE = ∫ dp/dt dx

- F = dp/dt, i.e. force equals the time rate of change of momentum.

- So 2 follows from 1 by replacing F with dp/dt.

- KE = ∫ dp/dt v dt

- From 2 since dx = v dt, distance = velocity times time.

- KE = ∫ dp/dv dv/dt v dt

- From 3: differential chain rule: dp/dt = dp/dv dv/dt

- KE = ∫ dp/dv a v dt

- From 4: acceleration = time rate of change of velocity: dv/dt = a

- KE = ∫ dp/dv v dv

- From 5: velocity = acceleration times time: a dt = dv

- Continued below

Continuation: Kinetic Energy in Classical Mechanics

- 7. KE = ∫ d(mv)/dv v dv

- From 6: momentum = mass times velocity: p = mv

- 8. KE = 1/2 mv2

- Mathematica

- Integrate[D[m v, v] v, v] = mv2/2

- Mathematica

Continuation: Kinetic Energy in Relativistic Mechanics

- 7. KE = ∫ d(mvγ)/dv v dv

- From 6: momentum = mass times velocity times the Lorentz Factor : p = mvγ

- where the Lorentz Factor γ = 1/√(1 – v2/c2)

- From 6: momentum = mass times velocity times the Lorentz Factor : p = mvγ

- 8. KE = γmc2 = mc2/√(1 – v2/c2)

- Mathematica

- FullSimplify[Integrate[D[γ m v, v] v, v]]

- = mc2/Sqrt[1 – v2/c2]

- FullSimplify[Integrate[D[γ m v, v] v, v]]

- Mathematica

E = mc2

- E = mc2 says that the energy of a particle at rest equals its mass times the speed of light squared.

- The equation follows directly from the relativistic kinetic energy of particle, γmc2.

- γmc2 = mc2/√(1 – v2/c2)

- v = 0

- Therefore, γmc2 = mc2/√(1 – 0/c2) = mc2

- That is, mc2 is the “kinetic” energy of a particle at rest.

E = mc2 and Approximate Kinetic Energy

- A useful approximation of 1/√(1 – x2), where x is small, is 1 + x2/2.

- For example, where x = 1/1000:

- 1/√(1 – x2) = 1.000000500000375000312500

- 1 + x2/2 = 1.000000500000000000000000

- For example, where x = 1/1000:

- KE = mc2/√(1 – v2/c2)

- Therefore, KE ≅ mc2 (1 + (v/c)2/2) = mc2 + 1/2 mv2

- Mathematica

- Expand[m c^2 (1 + (v/c)^2/2)]

- = c^2 m + (m v^2)/2

- Expand[m c^2 (1 + (v/c)^2/2)]

- Mathematica

- Thus, the energy of a particle is its rest energy plus its approximate kinetic energy in Classical Mechanics.

E = mc2 in Action: Particle Annihilation

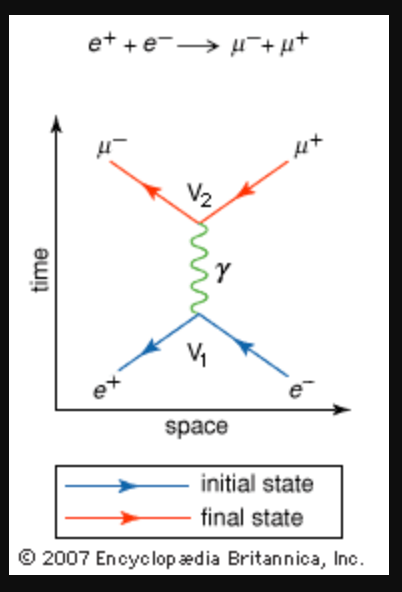

- In the Feynman Diagram at right an electron (e–) and its antiparticle, the positron (e+), annihilate each other when they collide at V1, creating a gamma ray photon γ, which at V2 becomes a muon (𝜇–) and an antimuon (𝜇+). Energy is conserved throughout the process:

- me+c2/√(1 – v2/c2) + me-c2/√(1 – v2/c2) = the energy of the gamma ray photon = mμ+c2/√(1 – v2/c2) + mμ–c2/√(1 – v2/c2).