Back to Free Will and Determinism

Outline

- Moral Responsibility

- Determinism and Moral Responsibility

- Scenarios

- Principle of Alternate Possibilities (PAP)

- Argument that Determinism + PAP Implies No Moral Responsibility

- Frankfurt-style Counterexamples to Premise 2 of PAP

- How to Make a Frankfurt-style Counterexample

- Thesis that Determinism Implies No Moral Responsibility

- How Free Will, FSC’s, and Determinism Look

- Frankfurt’s Orginal Counterexample

Moral Responsibility

- The core of morally responsibility is deserving or being worthy of blame or punishment, praise or reward.

- A person can be morally responsible for an:

- event, e.g. the he death of someone due to negligence.

- act, e.g. the assassination of the head of state

- omission, e.g. failing to save a drowning person you could easily have saved.

Determinism and Moral Responsibility

- Argument that Determinism + PAP Implies No Moral Responsibility

- If determinism is true, no one could have avoided anything they do.

- That is, free will and determinism are incompatible

- A person is morally responsible for doing something only if they could have avoided doing it

- This is the Principle of Alternate Possibilities (PAP)

- Therefore, if determinism is true, no one is morally responsible for anything they do.

- In particular, no one deserves to be punished for anything they do

- If determinism is true, no one could have avoided anything they do.

- There is a disputed kind of counterexample to the second premise, what are called Frankfurt-style counterexamples.

- Even if the second premise is false, the conclusion can still be defended in its own right.

Scenarios

- Determining whether a person who’s caused someone’s death is morally responsible is not always straightforward.

- Assassinating the head of state

- Shooting someone with a gun they thought was unloaded

- Alec Baldwin

- While enjoying a beer after a day of hunting, one of the hunters picks up an automatic handgun and, thinking it’s unloaded (because the magazine had been removed), points the gun at a friend and pulls the trigger as a joke.

- Car Accident

- You hit a child who darts in front of your car.

- Your brakes don’t work and you kill a motorcyclist at a stop light.

- Physical Altercation

- You push someone who falls, hits their head, and dies

- Insanity

- A person kills someone because they believed they were commanded by God.

- A man with schizophrenia pushes a woman onto the tracks in front of an oncoming subway train.

- Self-Defense

- A homeowner kills a man knocking on his door at night because he regards the man as a threat.

- Mistaken Good Samaritan

- A person with a handgun license comes upon a shootout and kills a police officer by mistake.

Principle of Alternate Possibilities (PAP)

Moral Responsibility Requires Free Will

- PAP for Actions

- A person is morally responsible for something they did only if they could have avoided doing it.

- PAP for Omissions

- A person is morally responsible for something they did not do only if they could have avoided not doing it.

- PAP for Events

- A person is morally responsible for an event only if they could have prevented it.

View Why Could Have Avoided is preferable to Could Have Done Otherwise

Tout comprendre c’est tout pardonner

Merriam-Webster

Argument that Determinism + PAP Implies No Moral Responsibility

For Actions

- If determinism is true, no one could have avoided anything they do.

- A person is morally responsible for doing something only if they could have avoided doing it

- Therefore, if determinism is true, no one is morally responsible for anything they do.

- In particular, no one deserves to be punished for anything they do

For Omissions

- If determinism is true, no one could have avoided not doing something.

- A person is morally responsible for not doing something only if they could have avoided not doing it.

- Therefore, if determinism is true, no one is morally responsible for not doing something

- In particular, no one deserves to be punished for not doing something.

For Preventing Events

- If determinism is true, no one could have prevented any event from happening

- A person is morally responsible for an event only if they could have prevented it

- Therefore, if determinism is true, no one is morally responsible for any event that happens.

- In particular, no one deserves to be punished for not preventing an event from happening

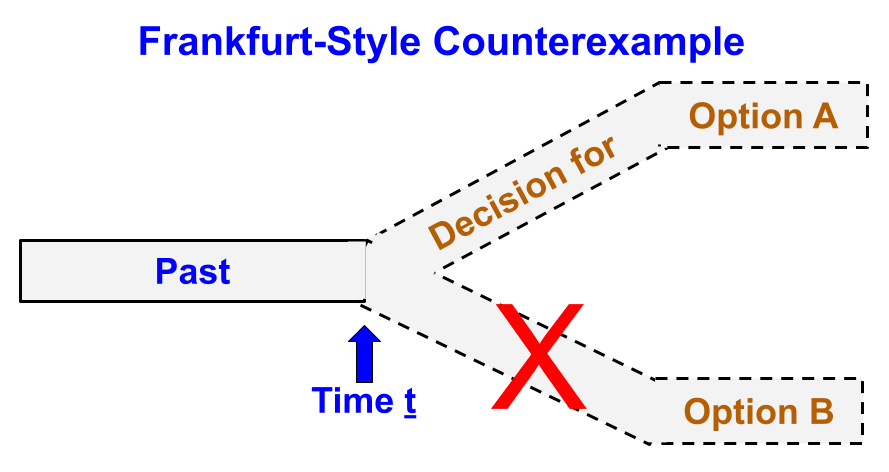

Frankfurt-style Counterexamples to Premise 2 of PAP

Counterfactual Intervenor

- John Martin Fischer, “Responsibility and Control”, 1982 Journal of Philosophy

- Black is a nefarious neurosurgeon. In performing an operation on Jones to remove a brain tumor, Black inserts a mechanism into Jones’s brain which enables Black to monitor and control Jones’s activities. Jones, meanwhile, knows nothing of this. Black exercises this control through a computer which he has programmed so that, among other things, it monitors Jones’s voting behavior. If Jones shows an inclination to decide to vote for [the Democrat], then the computer, through the mechanism in Jones’s brain, intervenes to assure that he actually decides to vote for [the Republican], and does so vote. But if Jones decides on his own to vote for [the Republican], the computer does nothing but continue to monitor—without affecting—the goings-on in Jones’s head. Suppose Jones decides to vote for [the Republican] on his own, just as he would have if Black had not inserted the mechanism into his head. Then Jones is responsible for voting for [the Republican], regardless of the fact that he could not have done otherwise.

Blocked Alternative

- David P Hunt, “Moral Responsibility and Unavoidable Action”, 2000, Philosophical Studies

- Neural processes leading up to Jones’ decision for whom to vote proceed without any outside interference. But while these processes are indeterministic, it turns out that all of the alternative neural pathways—those that might have realized a decision to vote for the Democrat—have been blocked. Such “blockage” (Fischer 1999) gives Jones no alternative but to vote for the Republican, yet he still makes the decision on his own—the blockage never plays a role in his deliberations—and is thus morally responsible for it.

How to Make a Frankfurt-style Counterexample

- Build a scenario where an agent deliberates, decides, and takes action — all of his own categorical free will.

- Then prevent every alternative course of action throughout the process either by a counterfactual intervening mechanism or by a neural block of some sort. Alternatives are blocked for:

- the agent’s mental acts during deliberation

- the agent’s decision

- the agent’s not changing his mind

- the agent’s action.

- The agent is morally responsible because they enjoy categorical free will at every point, though alternatives are blocked.

- The key difference between a Frankfurt-style counterexample and its completely deterministic counterpart is that in the former the agent has categorical free will (though blocked) but in the latter the agent has no categorical free will at all.

- Frankfurt-style counterexamples establish that the second premise of the PAP Argument above is not necessarily true. The argument thus fails.

Thesis that Determinism Implies No Moral Responsibility

- That the PAP Argument fails does not mean its conclusion is false.

- Moreover the conclusion is not subject to Frankfurt-style counterexamples, since FSC’s require that some events be undetermined.

- Thus the Hard Determinist does not need PAP to argue that if determinism is true no one is morally responsible for anything.

- David Robb, from Moral Responsibility and the Principle of Alternative Possibilities

- “In FSCs, what makes the action inevitable doesn’t interfere with the agent’s own deliberative processes or actions: the “intervention” in these examples is merely counterfactual. By contrast, if determinism is true, its intervention is actual. After all, determinism entails that every detail of how we choose and act is fixed by factors in the distant past. As one might put it: in a deterministic world, we act as we do because determinism has put us on the single track, because we could not do otherwise. So even if FSCs show that the mere blocking of alternatives does not preclude moral responsibility, determinism’s distinctive way of blocking alternatives is still a threat.”

How Free Will, FSC’s, and Determinism Look

FSC’s and Determinism prevent a person from doing otherwise in different ways. FSC’s prevent doing otherwise by blocking alternatives to categorical free will. Determinism blocks doing otherwise through the logical entailment of decisions and actions by things beyond the person’s control.

Frankfurt’s Orginal Counterexample

- Harry Frankfurt, “Alternate Possibilities and Moral Responsibility,” Journal of Philosophy 66 (1969), pp. 829-839.

- Suppose someone — Black, let us say — wants Jones to perform a certain action. Black is prepared to go to considerable lengths to get his way, but he prefers to avoid showing his hand unnecessarily. So he waits until Jones is about to make up his mind what to do, and he does nothing unless it is clear to him (Black is an excellent judge of such things) that Jones is going to decide to do something other than what he wants him to do. If it does become clear that Jones is going to decide to do something else, Black takes effective steps to ensure that Jones decides to do, and that he does do, what he wants him to do. Whatever Jones’ initial preferences and inclinations, then, Black will have his way. … Now suppose that Black never has to show his hand because Jones, for reasons of his own, decides to perform and does perform the very action Black wants him to perform. In that case, it seems clear, Jones will bear precisely the same moral responsibility for what he does as he would have borne if Black had not been ready to take steps to ensure that he do it. … In this example there are sufficient conditions for Jones’ performing the action in question. What action he performs is not up to him. … But whether he finally acts on his own or as a result of Black’s intervention, he performs the same action. He has no alternative but to do what Black wants him to do. If he does it on his own, however, his moral responsibility for doing it is not affected by the fact that Black was lurking in the background with sinister intent, since this intent never comes into play.