Contents

Absolute Idealism

- Science progressed in the 19th century, developing the atomic theory, the theory of electromagnetism, thermodynamics, and the theory of evolution. Mathematics also made progress, led by Gauss, Riemann, and Poincare. But philosophy, with a few exceptions, regressed.

- Absolute Idealism, the philosophical school that dominated the century, is characterized by the following principles, according to the Britannica:

- “The common everyday world of things and embodied minds is not the world as it really is but merely as it appears in terms of uncriticized categories.”

- “The best reflection of the world is not found in physical and mathematical categories but in terms of a self-conscious mind.”

- “Thought is the relation of each particular experience with the infinite whole of which it is an expression, rather than the imposition of ready-made forms upon given material.”

- German Absolute Idealism dominated the first half of the century, led by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Johann Fichte, and Friedrich Schelling.

- British Absolute Idealism, championed by T. H. Green, Bernard Bosanquet, and F.H. Bradley, dominated the last half.

A Taste of Absolute Idealism

- In his major work, Appearance and Reality: A Metaphysical Essay (1893), F. H. Bradley tries to prove that aspects of the everyday world are contradictory and therefore not real.

- For example, he argues that time and space are not real.

- “Time, like space, has most evidently proved not to be real, but to be a contradictory appearance.”

- For Bradley, there’s an appearance of time and an appearance of space but, since the concepts of time and space are self-contradictory, time and space themselves can’t be real.

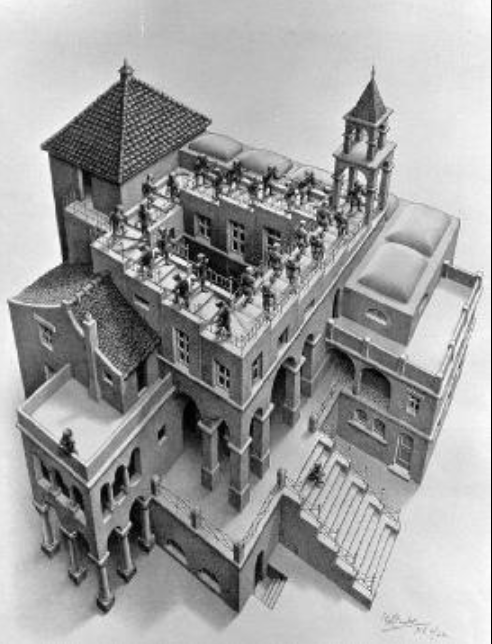

- Like M.C. Escher’s lithograph “Ascending and Descending”:

- Like M.C. Escher’s lithograph “Ascending and Descending”:

- So Bradley tries to prove that the concepts of space and time are self-contradictory, like the concept of a unmarried husband. The problem is trying to make sense of his arguments.

- For example, his overall argument that space is unreal is this:

- (1) If space is real, space is not a mere relation.

- (2) If space is real, space is nothing but a relation.

- (3) Premises (1) and (2) can’t both be true.

- (4) Therefore, space isn’t real.

- But the arguments for premises (1) and (2) are beyond comprehension. I leave you with the argument for the first premise:

- “Space is not a mere relation. For any space must consist of extended parts and these parts are clearly spaces. So that, even if we could take our space as a collection, it would be a collection of solids. The relations would join spaces which would not be mere relations. And hence the collection, if taken as a mere inter-relation, would not be space. We should be brought to the proposition that space is nothing but a relation of spaces. And this proposition contradicts itself.

- Again, from the other side, if any space is taken as a whole, it is evidently more than a relation. It is a thing, or substance, or quality (call it what you please), which is clearly as solid as the parts which it unites. From without, or from within, it is quite repulsive and as simple as any of its contents. The mere fact that we are driven always to speak of its parts should be evidence enough. What could be the parts of a relation?”

Exceptions

John Stuart Mill

- Mill, “the most influential English language philosopher of the nineteenth century,” was an empiricist, utilitarian, and liberal. His important works are:

- A System of Logic (1843)

- On Liberty (1859)

- Utilitarianism (1861)

- An Examination of Sir William Hamilton’s Philosophy (1865)

- The Subjection of Women (1869)

Gotlob Frege

- Toward the end of the century, Gotlob Frege developed Predicate Logic, the foundation of modern symbolic logic.

- Here’s an example of a proof in Predicate Logic, the proof of the validity of the argument that:

- If a first integer is greater than a second, the second is not greater than the first.

- Therefore, no integer is greater than itself.

- Proof

- (x)(y)(Gxy → ~Gyx)

- For any integers x and y, if x > y then it’s false that y > x.

- (y)(Gay → ~Gya)

- Gaa → ~Gaa

- ~Gaa

- (x)~Gxx

- ~(∃x)Gxx

- It’s false that there at least one integer x such that x > x.

- (x)(y)(Gxy → ~Gyx)