Outline of Tyranny of the Minority: Why American Democracy Reached the Breaking Point

by Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky

Contents

- The Book

- My Top-Level Outline

- Chapter Summary

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Fear of Losing

- Chapter 2: The Banality Of Authoritarianism

- Chapter 3 It Has Happened Here

- Chapter 4 Why the Republican Party Abandoned Democracy

- Chapter 5 Fettered Majorities

- Chapter 6 Minority Rule

- Chapter 7 America the Outlier

- Chapter 8 Democratizing Our Democracy

- Addendum

- Detailed Table of Contents

The Book

- Tyranny of the Minority: Why American Democracy Reached the Breaking Point

- Published in 2023

- Available in

- Hardcover

- Paperback

- Kindle

- Kindle App

- Audible Book

- By Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky

- Photo

- Daniel Ziblatt is Eaton Professor of the Science of Government at Harvard University

- Steven Levitsky is the David Rockefeller Professor of Latin American Studies and Professor of Government at Harvard University

- They wrote How Democracies Die, published in 2018

- The concept that runs through the book is the democratic norm, an established and respected unwritten rule that reinforces the Constitution.

- View Outline of How Democracies Die

- Reviews and Commentary

- GoodReads

- How Do We Survive the Constitution? New Yorker

- Why is American democracy on the brink? Blame the Constitution WaPo

- Is America uniquely vulnerable to tyranny? Zack Beauchamp Vox

- Can an Unpopular Populist Still Damage Democracy? Edsall nyt

My Top-Level Outline

A. The Constitution has flaws that enable partisan minorities to impede or block majorities.

Flaws

- A severely malapportioned Senate, in which all states are given the same representation regardless of population.

- The Electoral College, an indirect system of electing presidents that privileges smaller states and allows losers of the popular vote to win the presidency.

- In four elections so far, a candidate was elected president although more people voted for someone else.

- The presidents: Rutherford B. Hayes (1876), Benjamin Harrison (1888), George W. Bush (2000), Donald Trump (2016).

- Why Framers Chose the Electoral College

- Extreme supermajority rules for amending the Constitution, requiring a two-thirds vote of each house of Congress plus approval by three-quarters of U.S. states.

- The Supreme Court, with power of judicial review and lifetime appointments for justices.

- A bicameral Congress, which means that two legislative majorities are required to pass laws.

- The filibuster, a supermajority rule in the Senate (not in the Constitution) that allows a partisan minority to permanently block legislation backed by the majority.

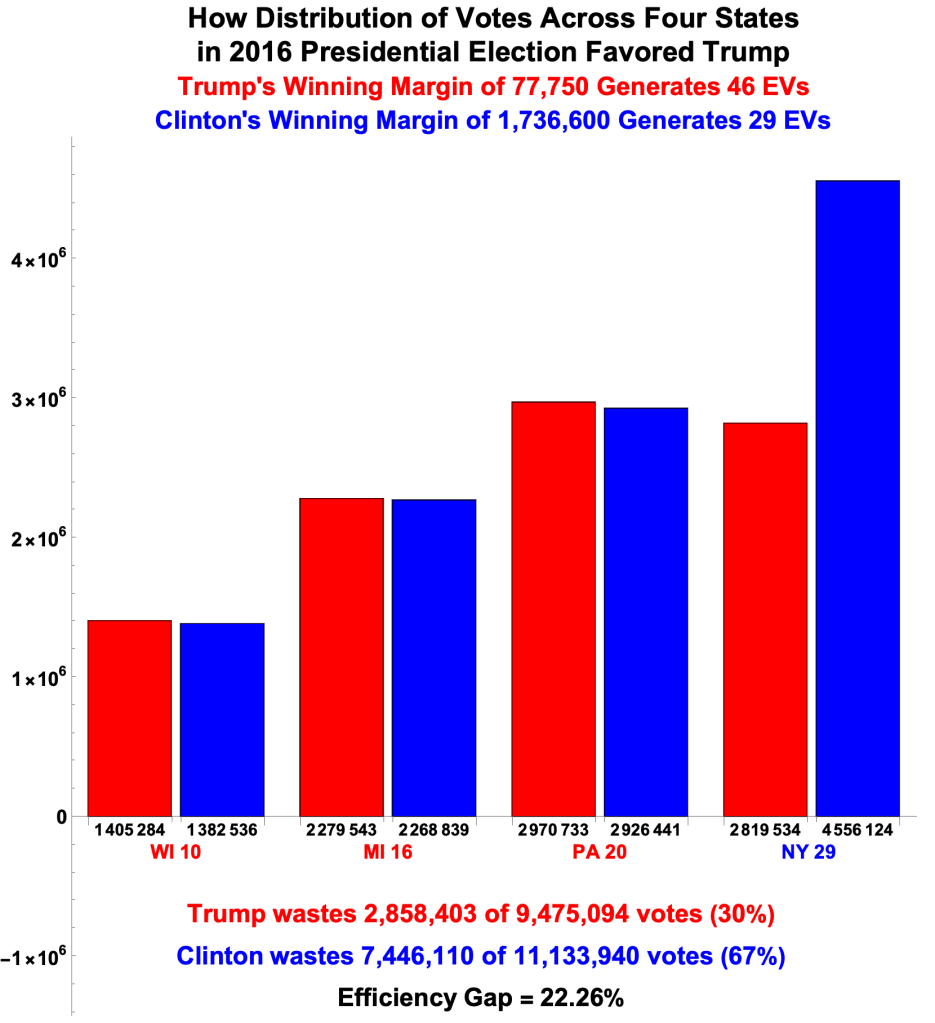

- An electoral system of “manufactured majorities” that enables parties that win fewer votes to control legislatures.

- In elections for the House of Representatives, the proportion of seats a party wins depends not only on the proportion of votes it receives but also on how “efficiently” its votes are distributed across electoral districts. Thus, the proportion of seats a party wins may be different from the proportion of votes it receives.

- View Bar Chart Depicting Relative Efficiency of Votes in 2018 Election for the Pennsylvania State Legislature

Chapters

- Chapter 5 Fettered Majorities

- Principles of Democratic Rule

- In elections, those with more votes should prevail over those with fewer votes.

- Legislative majorities should be able to pass laws

- Democracies must

- protect individuals against the “tyranny of the majority”

- prevent the majority from installing authoritarian rule.

- Thus the need for counter-majoritarian institutions. But those institutions must be prevented from impeding and obstructing the majority from governing.

- merriam-webster.com/dictionary/majoritarianism

- the philosophy or practice according to which decisions of an organized group should be made by a numerical majority of its members

- Principles of Democratic Rule

- Chapter 7 America the Outlier

- US lags behind other democracies in making democratic reforms

- Chapter 8 Democratizing Our Democracy

- Democracy in the US should be changed to:

- Uphold the right to vote

- Ensure that election outcomes reflect majority preferences

- Empower governing majorities

- Democracy in the US should be changed to:

B. The Republican Party evolved from the Party of Lincoln and Reconstruction into the Party of Racial Conservatism

Chapters

- Chapter 3 It Has Happened Here

- Republicans attempted to establish a multiracial democracy after the Civil War.

- The result was a white backlash that took the form of terrorism, Jim Crow Laws, and 90 years of Democratic Party control of the Solid South.

- Chapter 4 Why the Republican Party Abandoned Democracy

- As Democrats fought for civil rights beginning in the mid 20th century, the Republican Party pursued a “Southern Strategy,” resulting in its takeover of the “Solid South.”

- And then “the Republican Party was captured by its racially conservative base.”

C. The flaws in the Constitution now give the Republican Party an electoral advantage

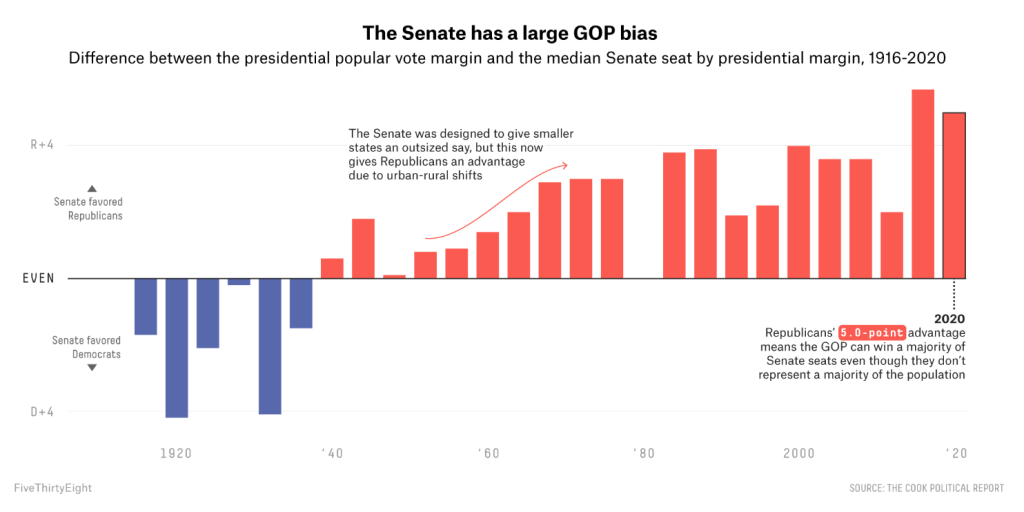

Small-State bias has become a Partisan Bias

- Republicans are predominantly the party of sparsely populated regions, while Democrats are the party of the cities. As a result, the Constitution’s small-state bias, which became a rural bias in the twentieth century, has become a partisan bias in the twenty-first century.

The Senate, for Example

- States with 1 Rep Senator and 1 Dem Senator: MT, WV, WI, OH

- States with 1 Dem Senator and 1 Indy Senator VT, AZ

- States with 1 Rep Senator and 1 Indy Senator: ME

Chapter

- Chapter 6 Minority Rule

- Flaws in the Constitution, together with the partisan urban-rural divide, have given the Republican Party an electoral advantage in:

- the Senate, since states have equal representation, no matter the size of their populations

- the Electoral College, since a state has at least 3 electoral votes, no matter its population.

- the Supreme Court, because presidents nominate Supreme Court justices and the Senate confirms them

- the House and State Legislatures, since the proportion of seats a party wins depends not just on its proportion of the vote but also on how those votes are distributed across districts

- “Flaws in our Constitution now imperil our democracy.”

- Flaws in the Constitution, together with the partisan urban-rural divide, have given the Republican Party an electoral advantage in:

Chapter Summary

- Introduction

- Demographic changes in the U.S have transformed what had been a predominantly white Christian society into a diverse and multiethnic one.

- The changes resulted in an authoritarian backlash: a surge in politically motivated violence; threats against election workers; efforts to make it harder for people to vote; a campaign by the president to overturn the results of an election.

- Part of the problem we face today lies in the US Constitution, which allows partisan minorities to routinely thwart majorities, and sometimes even govern them. Institutions that empower partisan minorities can become instruments of minority rule. And they are especially dangerous when they are in the hands of extremist or antidemocratic partisan minorities.

- Chapter 1 Fear of Losing

- The norm of accepting defeat and peacefully relinquishing power is the foundation of modern democracy.

- But accepting defeat gets harder when parties are fearful they will lose not just elections but their place in society and way of life.

- Chapter 2 The Banality Of Authoritarianism

- Most twenty-first-century autocracies are built via “constitutional hardball”: using the law to eliminate the opposition and undermine democracy.

- Constitutional hardball includes

- exploiting gaps in constitutions

- excessive or undue use of the law

- selective enforcement

- lawfare.

- Constitutional hardball includes

- Many of the politicians who preside over a democracy’s collapse are just ambitious careerists trying to stay in office. Rather than oppose democracy out of principle, they tolerate antidemocratic extremism because it is the path of least resistance.

- Most twenty-first-century autocracies are built via “constitutional hardball”: using the law to eliminate the opposition and undermine democracy.

- Chapter 3 It Has Happened Here

- The Republican Party attempted to establish multiracial democracy after the Civil War. The result was a white backlash that took the form of terrorism, Jim Crow Laws, and 90 years of Democratic Party control of the Solid South.

- Chapter 4 Why the Republican Party Abandoned Democracy

- As Democrats began championing civil rights in the 20th century, Republicans pursued their southern strategy, eventually capturing the Democrat’s Solid South. By the Obama era, racially conservative whites, who feared the country’s demographic shift toward more diversity, had become a solid majority in the party. Thus “the Republican Party was captured by its racially conservative base.”

- Chapter 5 Fettered Majorities

- Democracies must

- protect individual liberty against the “tyranny of the majority”

- prevent the majority from installing authoritarian rule.

- Thus the need for counter-majoritarian institutions. But the danger such institutions pose is that they can enable partisan minorities that prevent the majority from governing.

- Democracies must

- Chapter 6 Minority Rule

- Because of the counter-majoritarian features of the Constitution and the partisan urban-rural divide, the Constitution now gives the Republican Party an electoral advantage.

- Chapter 7 America the Outlier

- Though the US took important steps toward majority rule in the twentieth century, the reforms did not go as far as other democracies.

- Chapter 8 Democratizing Our Democracy

- Democracy in the US should be changed to:

- Uphold the right to vote

- Ensure that election outcomes reflect majority preferences

- Empower governing majorities

- Democracy in the US should be changed to:

- Notes

- Lots of references

Introduction

- Demographic changes in the U.S have transformed what had been a predominantly white Christian society into a diverse and multiethnic one.

- britannica.com/topic/demographics

- The characteristics of a large population over a specific time interval, characteristics such as age, race, gender, ethnicity, religion, income, education, home ownership, sexual orientation, marital status, family size, health and disability status, and psychiatric diagnosis.

- britannica.com/topic/demographics

- The changes resulted in an authoritarian backlash: a surge in politically motivated violence; threats against election workers; efforts to make it harder for people to vote; a campaign by the president to overturn the results of an election.

- The republic became less democratic between 2016 and 2021.

- Freedom House’s Global Freedom Index for the US went from 90 in 2015 (in line with countries like Canada, Italy, France, Germany, Japan, Spain, and the U.K) to 83 in 2021 (lower than democracies like Argentina, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, and Taiwan)

- Part of the problem we face today lies in something many of us venerate: our Constitution. For more than two centuries it has succeeded in checking the power of ambitious and overreaching presidents. But flaws in our Constitution now imperil our democracy.

- Designed in a pre-democratic era, the U.S. Constitution allows partisan minorities to routinely thwart majorities, and sometimes even govern them. Institutions that empower partisan minorities can become instruments of minority rule. And they are especially dangerous when they are in the hands of extremist or antidemocratic partisan minorities.

- Prominent eighteenth- and nineteenth-century thinkers worried that democracy risked becoming a “tyranny of the majority”—that such a system would allow the will of the many to trample on the rights of the few. But the American political system has always reliably checked the power of majorities. What ails American democracy today is closer to the opposite problem: Electoral majorities often cannot win power, and when they win, they often cannot govern. The more imminent threat facing us today, then, is minority rule.

Chapter 1 Fear of Losing

- The norm of accepting defeat and peacefully relinquishing power is the foundation of modern democracy.

- The Peronists accepted defeat in Argentina’s 1983 election, Page 12

- The Federalists accepted defeat in their 1800 loss to the Democratic-Republicans, Page 15

- On March 4, 1801, the United States became the first republic in history to experience an electoral transfer of power from one political party to another.

- But accepting defeat gets harder when parties are fearful they will lose not just an election but their place in society and way of life.

- Research in political psychology teaches us that social status—where one stands in relation to others—can powerfully shape political attitudes. We often gauge our social status in terms of the status of the groups we identify with. Those groups may be based on social class, religion, geographic region, or race or ethnicity, and where they sit in the larger societal pecking order greatly affects our own individual sense of self-worth. Economic, demographic, cultural, and political change may challenge existing social hierarchies, raising the status of some groups and, inevitably, lowering the relative status of others. What the writer Barbara Ehrenreich called the “fear of falling” can be a powerful force. When a political party represents a group that perceives itself to be losing ground, it often radicalizes. With their constituents’ way of life seemingly at stake, party leaders feel pressure to win at any cost. Losing is no longer acceptable.

- The Democrat Party in Thailand, which once supported democracy and opposed coups and absolutist royal power, supported the 2014 coup, Page 25

- When democracy gave rise to a movement that challenged the social, cultural, and political dominance of the Bangkok elite, the Democrats turned against democracy.

- Existential fear thwarted the emergence of democracy in early twentieth-century Germany, Page 24

- Parties are more likely to accept defeat when they believe that

- they stand a reasonable chance of winning again in the future.

- losing power will not bring catastrophe—that a change of government will not threaten the lives, livelihoods, or most cherished principles of the outgoing party and its constituents.

Chapter 2: The Banality Of Authoritarianism

Banality of Authoritarianism

- Many politicians who preside over a democracy’s collapse are just ambitious careerists trying to stay in office. Rather than opposing democracy out of principle, they tolerate antidemocratic extremism because it is the path of least resistance.

- britannica.com/biography/Hannah-Arendt

- In a highly controversial work, Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), based on her reportage of the trial of the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in 1961, Arendt argued that Eichmann’s crimes resulted not from a wicked or depraved character but from sheer “thoughtlessness”: he was simply an ambitious bureaucrat who failed to reflect on the enormity of what he was doing.

Constitutional Hardball

- Most twenty-first-century autocracies are built via “constitutional hardball”: using the law to eliminate opposition and undermine democracy. Such democratic backsliding occurs gradually, through a series of reasonable-looking measures:

- new laws that are ostensibly designed to clean up elections, combat corruption, or create a more efficient judiciary;

- court rulings that reinterpret existing laws;

- long-dormant laws that are conveniently rediscovered.

- Because the measures are couched in legality, it may appear as if little has changed. No blood has been shed. No one has been arrested or sent into exile. Parliament remains open. So criticism of the government’s measures is dismissed as alarmism or partisan bellyaching. But gradually, and sometimes almost imperceptibly, the playing field tilts. The cumulative effect of these seemingly innocuous measures is to make it harder for opponents of the government to compete—and thereby entrench the incumbents in power.

Kinds of Constitutional Hardball

- Kinds

- Exploiting Gaps

- Excessive or Undue Use of the Law

- Selective Enforcement

- Lawfare

- Exploiting Gaps, Page 51

- No rule or set of rules covers all contingencies. There are always circumstances that are not explicitly covered by existing laws and procedures.

- Societies often develop norms—or unwritten rules—to fill in the gaps in the rules. But norms can’t be legally enforced.

- Example, Page 52

- In 2016 the Senate refused to let President Barack Obama appoint a new Supreme Court justice in the wake of Justice Antonin Scalia’s death.

- According to the Constitution, presidential nominees to the Supreme Court must have the consent of the Senate. But because the Constitution does not specify when the Senate must take up presidential court nominees, the theft was entirely legal.

- Norm

- Historically, the Senate used its power of “advice and consent” with forbearance. Most qualified nominees were promptly approved, even when the president’s party did not control the Senate. Indeed, in the 150-year span between 1866 and 2016, the Senate never once prevented an elected president from filling a Supreme Court vacancy. Every president who attempted to fill a court vacancy before the election of his successor was eventually able to do so (though not always on the first try)

- Denying the president’s ability to fill a Supreme Court vacancy clearly violated the spirit of the Constitution.

- Excessive or Undue Use of the Law, Page 52

- Some rules are designed to be used sparingly, or only under exceptional circumstances.

- Example: Presidential Pardons

- If U.S. presidents used their constitutional pardon authority to the full extent, they could not only systematically pardon friends, relatives, and donors but also legally pardon political aides and allies who commit crimes on their behalf, in the knowledge that if caught, they will be pardoned

- Example: Impeaching a President

- Impeaching a president involves overturning the will of voters, which is a momentous event for any democracy. So impeachment should be rare—used only when presidents egregiously or dangerously abuse their power.

- Peru: Congress “vacated” three presidents in a span of four years.

- Example: Abuse of State of Emergency

- In 1975 Indira Gandhi persuaded India’s ceremonial president to sign a declaration of emergency, suspending constitutional rights. Within 24 hours 676 politicians—including the leaders of all major opposition parties—were in jail. The government arrested more than 110,000 critics in 1975 and 1976. Page 55

- Example: Presidential Pardons

- Some rules are designed to be used sparingly, or only under exceptional circumstances.

- Selective Enforcement, Page 57

- Wherever nonenforcement of the law is the norm—where people routinely cheat on their taxes, businesses routinely flout health, safety, or environmental regulations, and well-placed public officials routinely use their influence to do favors for friends and family members—enforcement can be a form of constitutional hardball. Governments may enforce the law selectively, targeting their rivals.

- Lawfare, Page 58

- Politicians may design new laws that, while seemingly impartial, are crafted to target opponents.

- Example: Zambia 1991, Page 58

A model for Building an Autocracy by Constitutional Hardball

- The model for building an autocracy via constitutional hardball is Viktor Orban, Page 60

- Orbán used his party’s parliamentary supermajority to build an unfair advantage over his opponents.

- One of his first moves was to purge and pack the courts.

- Orbán also used “legal” means to capture the media.

- Under Orbán, public television became the government’s propaganda arm.

- The government banned the use of campaign advertisements in commercial media

- Orbán also legally captured the private media. In 2016, the newspaper Népszabadság, Hungary’s largest opposition newspaper, was suddenly closed, not by the government, but by its own corporate owners.

- The Orbán government used constitutional hardball to tilt the electoral playing field.

- It packed the Electoral Commission, which prior to 2010 was appointed via multiparty consensus.

- The politicized Electoral Commission then egregiously gerrymandered parliamentary election districts to overrepresent Fidesz’s rural strongholds and underrepresent the opposition’s urban strongholds.

- All these efforts paid off.

- In the 2014 election, Fidesz lost 600,000 votes relative to 2010; its share of the popular vote fell from 53 percent to 45 percent. And yet it captured the same number of seats as in 2010, retaining control of two-thirds of parliament despite failing to win a majority of the vote.

- Fidesz repeated the trick in 2018, winning two-thirds of parliament with less than half the popular vote.

- In 2022, the ruling party defeated a broad opposition coalition, reinforcing the emerging conventional wisdom that Orbán “cannot be defeated under ‘normal’ circumstances.”

Chapter 3 It Has Happened Here

Wilmington Coup and Massacre, 1898

- The largest city in North Carolina, Wilmington was majority Black. And as its post–Civil War economy expanded, numerous Black-owned businesses had sprung up—barbershops, grocery stores, restaurants, butcher shops, and soon doctor’s offices and a law firm. Black Wilmington became wealthier, which gave rise to a vibrant civic life of literary societies, public libraries, baseball leagues, and a Black-owned newspaper. At the center of the community were several churches, including St. Stephen A.M.E. Church, with its large congregation, and St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, which was attended by the most affluent Black families.

- The Fusion ticket won a sweeping majority in the North Carolina state legislature in 1894, and in 1896 it captured the governorship and elected to the House of Representatives George Henry White, who at the time was America’s only African American congressman.

- In Wilmington, three Black aldermen were elected to the city council. Ten of twenty-one city policemen and four deputy sheriffs were Black. Black magistrates sat in the courthouses. The county treasurer, the county jailer, and the county coroner were Black. There were Black health inspectors, Black registrars of deeds, and a Black superintendent of streets. Black postal workers delivered mail to Black and white homes alike.

- On November 10, in one of the most brutal domestic terrorist attacks in American history, a mob of at least five hundred white supremacists, armed and dressed in their paramilitary red shirts, marched through the streets of Wilmington, shooting bystanders, attacking Black churches, and burning the city’s only Black-owned newspaper to the ground.

- After reclaiming statewide power in North Carolina, the Democrats quickly amended the state constitution to impose a series of suffrage restrictions, including a poll tax, literacy tests, and property requirements.

- britannica.com/event/Wilmington-coup-and-massacre

- wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilmington_massacre

Reconstruction, 1865 -1877

- The historian Eric Foner describes the Reconstruction era as America’s “Second Founding,” a moment when the constitutional order was broken and then remade, leading to a “stunning and unprecedented experiment in interracial democracy.”

- Eric Foner

- britannica.com/event/Reconstruction-United-States-history

- The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution

- Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877

- Eric Foner

Reconstruction Amendments and Acts, 1865-1875

- Reconstruction Amendments

- The Thirteenth Amendment (1865) abolished slavery.

- The Fourteenth Amendment (1868) established birthright citizenship and formal equality before the law, giving rise to contemporary rights of due process and equal protection.

- And the Fifteenth Amendment (1870) prohibited restrictions on the right to vote on the basis of race.

- Reconstruction Acts

- The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 placed former Confederate states under federal military rule and made readmission to the Union conditional on passage of the Fourteenth Amendment and the writing of a new state constitution guaranteeing Black suffrage.

- Federal authorities launched a massive campaign to register newly enfranchised Black voters.

- The 1875 Civil Rights Act extended the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal treatment to everyday “public” places, such as streetcars, restaurants, theaters, and hotels. The act’s preamble recognized “the equality of all men before the law” and declared it “the duty of government in all its dealings with the people to mete out equal and exact justice to all, of whatever nativity, race, color, or persuasion.”

- The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 placed former Confederate states under federal military rule and made readmission to the Union conditional on passage of the Fourteenth Amendment and the writing of a new state constitution guaranteeing Black suffrage.

Reconstruction, the Work of One Party Alone

- The Reconstruction reforms were the work of one party alone: the Republican Party. In the U.S. Congress, no Democrat—from the North or South—voted for the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments or any of the subsequent voting and civil rights bills of the Reconstruction era.

Black Participation in Democracy

- Within one year, the percentage of Black men in America who were eligible to vote rose from 0.5 percent to 80.5 percent, with the entire increase coming from the former Confederacy. By 1867, at least 85 percent of African American men were registered to vote in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and North and South Carolina.

- By 1867, registered Black voters outnumbered registered whites across much of the Deep South.

- African Americans began to ascend to public office across the entire South, in some places in large numbers.

- African Americans won a majority of seats in the South Carolina legislature and a near majority in Louisiana; state legislatures in Mississippi and South Carolina elected Black speakers in 1872. There were Black lieutenant governors in Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina and Black secretaries of state in Florida, Mississippi, and South Carolina. Across the Deep South, African Americans filled important local offices, including justices of the peace, county supervisors, school commissioners, election commissioners, and even sheriffs.

- More than thirteen hundred Black Americans held public office during the Reconstruction era. Sixteen Black Americans were elected to the U.S. House and Senate during Reconstruction, and more than six hundred were elected to state legislatures.

White Backlash

- The prospect of multiracial democracy threatened southern whites in three ways:

- The former slaveholding elite feared losing its unfettered control over Black labor.

- Black suffrage jeopardized the political power of the Democratic Party, especially in states where African Americans were now a majority or near majority of the electorate.

- Democracy promised to upend long-established social and racial hierarchies.

Wave of Terrorism

- Since Black citizens were either majorities or near majorities in most southern states, white supremacists’ return to power would require, in W.E.B. Du Bois’s words, “brute force.” Backed by the Democratic Party, white supremacists organized paramilitary groups with names like the Whitecaps, the White Brotherhood, Jayhawkers, Pale Faces, and the Knights of the White Camellia.

- The largest of these, the Ku Klux Klan, emerged in Tennessee in early 1866 and quickly spread throughout the South.

- Klan terror crippled Republican organizations and kept Black voters from the polls, making a mockery of elections and allowing the Democrats to unconstitutionally seize power across the South—a process they euphemistically called “Redemption.”

- In Louisiana, a “civil war of secret assassination and open intimidation and murder” left at least five hundred African Americans dead.

- In Georgia, Klan terror so decimated Black turnout in the 1868 presidential election that eleven counties with Black majorities registered no Republican votes.

- In 1871, Klan pressure allowed Democrats to retake the state legislature and force the Republican governor, Rufus Bullock, to resign and flee the state.

- In North Carolina, Klan violence weakened the Republicans and enabled the Democrats to win a veto-proof majority in the state legislature, which they used to impeach and remove the Republican governor.

- In response, President Ulysses S. Grant and the Republican-dominated Congress passed a series of Enforcement Acts that empowered the federal government to oversee local elections and combat political violence.

- These included an 1870 law authorizing the president to appoint federal election supervisors with the power to press federal charges against anyone who engaged in electoral fraud, intimidation, or race-based voter suppression, as well as the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act, which allowed for federal prosecution and even military intervention to combat efforts to deprive citizens of basic rights. These laws were unprecedented in that they gave the federal government the authority to intervene in states to protect basic civil and voting rights—an essential component of multiracial democracy.

- Initially, these enforcement mechanisms worked. With the help of federal troops, hundreds of Klan members were arrested and prosecuted in 1871 and 1872, especially in Florida, Mississippi, and South Carolina. By 1872, federal authorities had “broken the Klan’s back and produced a dramatic decline in violence throughout the South.” According to the historian James McPherson, the 1872 election was “the fairest and most democratic election in the South until 1968.”

Waning of Reconstruction

- Eventually, the Republican Party divided. A faction known as the Liberal Republicans grew critical of the costs of enforcement. Prioritizing issues such as free trade and civil service reform, and skeptical of Black suffrage, the liberals began to question the wisdom of the Reconstruction project, preferring a more politically expedient “let alone” policy in the South.

- The multiracial democratic coalition was further undermined by the 1873 depression, which led to a sweeping Democratic takeover of the House of Representatives in 1874.

- Public opinion turned against federal intervention in the South, and civil rights activism faded to such a degree that The New York Times declared the “era of moral politics” to be over. In this new political climate, federal troops began to be withdrawn.

Second Wave of “Redemption”

- The turn away from federal protection permitted a second wave of Redemption.

- In 1875 the Mississippi Democrats launched a violent campaign—known as the Mississippi Plan—aimed at regaining the state legislature. As Foner notes, terrorist acts were “committed in broad daylight by undisguised men,” severely depressing the Black vote in the 1875 elections and giving Democrats control of the state legislature. They then impeached the African American lieutenant governor and forced the Republican governor, Adelbert Ames, to resign and flee the state. In South Carolina, the 1876 election was marred by Red Shirt terror and outright fraud. In what one observer described as “one of the grandest farces ever seen,” the Democrat Wade Hampton, a former Confederate officer, claimed the governorship.

End of Reconstruction, 1877

- By the time Grant’s successor, Rutherford B. Hayes, withdrew most of the remaining federal troops overseeing the South in 1877 (as part of a negotiated settlement of the disputed 1876 presidential election), Reconstruction had effectively ended.

- Democrats had seized power in every southern state except Florida and Louisiana.

- Overall, nearly two thousand Black Americans had been murdered in acts of terror during the ten years that followed the end of the Civil War, a rate of killing roughly equivalent to that of Pinochet’s Chile in the 1970s.

Biracial Coalitions Defy Rule by the Democratic Party in the South, 1880s

- A biracial Readjusters ticket won the Virginia governorship in 1881.

- Populist or Fusion tickets—backed by many Black voters—nearly won the governorship in Alabama in 1892, Virginia in 1893, Georgia in 1894, and Louisiana and Tennessee in 1896.

- A populist-Republican Fusion ticket won the governorship of North Carolina in 1896.

Jim Crow Laws, 1877-1954

- Concerned that acts of flagrant violence would attract national attention and trigger renewed federal oversight and enforcement, Democratic leaders across the South began the campaign to undermine democracy through legal channels. Between 1888 and 1908, they rewrote state constitutions and voting laws to disenfranchise African Americans using:

- Poll taxes

- Literacy tests

- Property and proof of residency requirements

- Secret ballots, which required citizens to vote on government-produced ballots—and alone in a voting booth where they could not be assisted by a (literate) friend

- To avoid also disenfranchising poor, illiterate whites, additional laws were passed:

- “Understanding clauses,” under which registrars would determine whether illiterate prospective voters demonstrated an “understanding” of the Constitution based on sections of the Constitution they read aloud. The laws were designed to give registrars the discretion to apply a higher bar for “understanding” to Black citizens than to white ones.

- “Grandfather clauses,” which allowed (white) illiterate or propertyless voters to register if they had voted before 1867 or were the descendants of pre-1867 voters.

- britannica.com/event/Jim-Crow-law

- wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_Crow_laws

Giles v. Harris, 1903

- In the 1890s, civil rights groups began filing lawsuits against state and county governments to protest the multitude of new laws targeting Blacks. Between 1895 and 1905, the Supreme Court heard six challenges to disenfranchisement efforts. The most decisive case was Giles v. Harris (1903).

- The lawsuit argued that Alabama’s 1901 constitution made registering to vote nearly impossible for Blacks.

- After passage of the constitution, only 3,000 of the more than 180,000 adult Black men in Alabama were eligible.

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, who wrote the opinion of the court, argued that since the complaint alleged that Alabama’s voter registration system was fraudulent, if the court were to grant relief to Giles and add another voter to the rolls, it would be complicit in Alabama’s fraud. Furthermore, Holmes argued, the court ought not to intervene because anything the court might mandate was unenforceable given the absence of federal troops or election supervisors to enforce it.

- supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/189/475/

- wikipedia.org/wiki/Giles_v._Harris

- The lawsuit argued that Alabama’s 1901 constitution made registering to vote nearly impossible for Blacks.

A Last Attempt to Pass Voting Rights Legislation, 1890

- The 1903 Giles v. Harris decision delivered the deathblow to America’s first experiment with multiracial democracy. It didn’t have to be this way. A brief political opening in the late 1880s had presented an alternative path—one that, if taken, might have set the country on a different course.

- In 1888, Benjamin Harrison, the Republican former senator from Indiana and a vocal supporter of more robust voting rights protections, was elected president, and the Republicans regained control of both houses of Congress. Moreover, Black suffrage and federal enforcement of voting laws remained in the Republican Party platform, which called for “effective legislation to secure the integrity and purity of elections.”

- Two influential Republican leaders, Senator George Frisbie Hoar and Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge (later U.S. senator), began work on a national plan to protect voting rights. It was the most ambitious voting rights bill in U.S. history, surpassing even the 1965 Voting Rights Act in its geographic scope, and it would have fundamentally altered the way elections were conducted in America.

- In the summer of 1890, solid Republican majorities in both houses of Congress seemed poised to pass the Lodge bill. President Harrison was ready to sign it. The bill passed the House of Representatives in July 1890 with the support of all but two Republicans.

- But then things began to unravel…..

- When the Lodge bill finally came up for debate in the Senate in January 1891, the minority Democrats turned to their last tool of obstructionism, the Senate’s filibuster—delivering speeches late into the night, issuing impossible amendment proposals, extending debate, and wandering the halls outside the main chamber to prevent a quorum. In a final desperate attempt to pass the bill, Republican leaders proposed a change to Senate rules to allow for the filibuster to be ended with a simple majority vote, thereby allowing the Senate majority to vote in favor of the Lodge bill. But the measure was blocked by a coalition of Democrats and western “silver” Republicans who had voted for currency reform. And so the Lodge bill, which might have preserved fair elections across the country, died by filibuster.

Chapter 4 Why the Republican Party Abandoned Democracy

V-Dem Illiberal Index

- The V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) Institute, which tracks global democracy, assigns the world’s major political parties an annual “illiberalism” score, which measures their deviation from democratic norms such as pluralism and civil rights, tolerance of the opposition, and the rejection of political violence. Most western European conservative parties receive a very low score, suggesting a strong commitment to democracy. So did the U.S. Republican Party—through the late 1990s. But the GOP’s illiberalism score soared in the twenty-first century. In 2020, V-Dem concluded that in terms of its commitment to democracy the Republican Party was now “more similar to autocratic ruling parties such as the Turkish AKP and Fidesz in Hungary than to typical center-right governing parties.”

- v-dem.net/documents/8/vparty_briefing.pdf

- Main Findings: V-Party’s 2020 Illiberalism Index shows that the Republican party in the US has retreated from upholding democratic norms in recent years. Its rhetoric is closer to authoritarian parties, such as AKP in Turkey and Fidesz in Hungary. Conversely, the Democratic party has retained a commitment to longstanding democratic standards.

- v-dem.net/documents/8/vparty_briefing.pdf

Southern Strategy

- GOP was in power from 1890 to 1930

- In the first half of the twentieth century, Republicans were a party of business and the well-to-do, with factions that included northeastern manufacturing interests, midwestern farmers, small-town conservatives, and white Protestant voters outside the South. This coalition allowed the Republicans to dominate national politics in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: between 1890 and 1930, the GOP controlled the presidency for thirty of forty years and the Senate for thirty-two of those years.

- GOP was out power from 1930 to 1953

- Things changed in the 1930s as the Great Depression and the New Deal reshaped American politics. Millions of urban working-class voters—Black and white—rejected the Republicans, establishing the New Deal Democrats as the new majority party. The Democrats won five consecutive presidential elections between 1932 and 1948.

- The civil rights revolution shook up America’s party system.

- As the party of Reconstruction, the GOP had almost no presence at mid-century in the Democratic “Solid South.” But in the late 1930s the Democratic Party began its gradual, tumultuous transformation from the party of Jim Crow into the party of cvil rights. Truman became the first Democratic president to openly embrace civil rights; and LBJ signed the Voting Rights Act into law in 1964. Southerners weren’t happy, providing the opening that would drive the “Long Southern Strategy”—a decades-long Republican effort to attract “white southerners who felt alienated from, angry at, and resentful of the policies that granted equality and sought to level the playing field for [minority] groups.” (See note on Long Southern Strategy.) Thus, the Republicans gradually repositioned themselves as the party of racial conservatism, appealing to voters who resisted the dismantling of traditional racial hierarchies.

- Goldwater actively pursued the southern white vote.

- He voted against the Civil Rights Act, championed “states’ rights,” and campaigned across the South, enthusiastically supported by segregationist Strom Thurmond.

- The GOP won the largest share of the white vote in every presidential election after 1964

- Richard Nixon’s “southern strategy” got results.

- Four-fifths of southern whites voted for either Nixon or the third-party candidate George Wallace in 1968.

- Four years later, Nixon won three-quarters of the Wallace vote en route to a landslide reelection.

- Ronald Reagan continued the southern strategy.

- He had opposed the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act in the 1960s and continued to embrace “states’ rights” into the 1980s.

- He launched his 1980 presidential campaign at the Neshoba County Fair in Philadelphia, Mississippi, where three civil rights activists had been brutally murdered in 1964.

- Reagan added a new prong—a white Christian strategy.

- Multiple issues triggered evangelical leaders’ entry into politics, including opposition to gay rights, the Equal Rights Amendment, and the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision. A major catalyst was the Carter administration’s efforts to desegregate private Christian schools by denying IRS tax exemption status to those that remained segregated. Under Falwell’s leadership, the Moral Majority embraced the Republican Party and campaigned hard for Reagan in 1980.

- Reagan was reelected in 1984 with 72 percent of the southern white vote and 80 percent of white evangelicals.

- Goldwater actively pursued the southern white vote.

- As the party of Reconstruction, the GOP had almost no presence at mid-century in the Democratic “Solid South.” But in the late 1930s the Democratic Party began its gradual, tumultuous transformation from the party of Jim Crow into the party of cvil rights. Truman became the first Democratic president to openly embrace civil rights; and LBJ signed the Voting Rights Act into law in 1964. Southerners weren’t happy, providing the opening that would drive the “Long Southern Strategy”—a decades-long Republican effort to attract “white southerners who felt alienated from, angry at, and resentful of the policies that granted equality and sought to level the playing field for [minority] groups.” (See note on Long Southern Strategy.) Thus, the Republicans gradually repositioned themselves as the party of racial conservatism, appealing to voters who resisted the dismantling of traditional racial hierarchies.

- The Republicans became America’s leading party, winning every presidential election between 1968 and 1988 except the 1976 post-Watergate election. In 1994, the Republicans captured the House of Representatives for the first time since 1955. By 1995, they controlled the House, the Senate, and thirty governorships.

Republican Party Captured by its Racially Conservative Base

- But if the Great White Switch created a new Republican majority, it also created a monster. By the turn of the century, surveys showed that a majority of white Republicans scored high on what political scientists call “racial resentment.” This mattered because, although the Republicans remained overwhelmingly white and Christian into the twenty-first century, America did not.

- Having spent four decades recruiting southern, conservative, and evangelical whites into a single tent, Republican politicians established the GOP as the undisputed home for white Christians who feared cultural and demographic change. According to the political scientist Alan Abramowitz, the proportion of white Republicans who scored high on survey-based “racial resentment” scores increased from 44 percent in the 1980s to 64 percent during the Obama era.

- The Republican Party was not, of course, a monolithic entity. Not all Republican voters were racial conservatives. But by the Obama era, racially conservative whites had become a solid majority in the party. This mattered a lot: the Republicans’ radicalizing voters exerted influence through primaries, where extremist challengers—many of them backed by the Tea Party—either defeated mainstream Republicans or pulled them to the right. The process of radicalization was facilitated by the evisceration of the Republican Party leadership. The rise of well-funded outside groups and influential right-wing media such as Fox News left the party especially vulnerable to capture.

Growing Diversity in America

- American society grew far more diverse in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

- The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which was passed with strong bipartisan support, opened the door to a long wave of immigration, particularly from Latin America and Asia.

- The percentage of Americans who were non-Hispanic white fell from 88 percent in 1950 to 69 percent in 2000 to just 58 percent in 2020.

- African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans now constituted 40 percent of the country.

- Whereas more than 80 percent of Americans identified as white and Christian (Protestant or Catholic) in 1976, only 43 percent did so in 2016.

- The number of African Americans in Congress (House and Senate) increased from seventeen in 1980 to sixty-one in 2021.

- Young Americans are less white and less Christian than their elders. In a 2014 PRRI survey, only 29 percent of respondents between the ages of eighteen and twenty-nine identified as white and Christian, compared with 67 percent of respondents over the age of sixty-five.

Change in Racial Hierarchy

- For nearly two hundred years, a white-dominated racial hierarchy was taken for granted. This changed dramatically in the twenty-first century. Not only was America no longer overwhelmingly white, but once-entrenched racial hierarchies were weakening. Challenges to white Americans’ long-standing social dominance left many of them with feelings of alienation, displacement, and deprivation.

- Whereas a large majority of African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and religiously unaffiliated Americans said things had changed for the better since the 1950s, 57 percent of whites and 72 percent of white evangelical Christians said things had changed for the worse.

- Surveys showed that whites’ perception of “anti-white bias” rose steadily beginning in the 1960s; by the early twenty-first century, a majority of white Americans believed that discrimination against whites had become at least as big a problem as discrimination against Blacks.

White Christian Nationalism

- Much of the resistance to multiracial democracy took the form of white Christian nationalism, or what the sociologist Philip Gorski describes as the belief that “the United States was founded by (white) Christians, and that (white) Christians are in danger of becoming a persecuted (national) minority.” “White Christians” were now less a religious group than an ethnic and political one.

- White Christian nationalism helped fuel the Tea Party movement, which emerged in February 2009—barely a month after Obama took office.

- Not only did the Republicans’ white Christian base radicalize in the face of a perceived existential threat, but it effectively captured the party.

Racial Resentment Score

- Racial resentment scores are based on individuals’ level of agreement or disagreement with four statements included in the American National Election Study:

- 1. Irish, Italian, Jewish, and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors.

- 2. Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class.

- 3. Over the past few years, blacks have gotten less than they deserve.

- 4. It’s really a matter of some people not trying hard enough; if blacks would only try harder they could be just as well off as whites.

- wikipedia.org/wiki/Racial_resentment_scale

Electoral Threat to the Republican Party

- The southern strategy created a new GOP majority. But that majority posed an electoral threat to the Republican Party

- The GOP remained an overwhelmingly white Christian party.

- In 2012, four out of five Republican voters were white and Christian (that is, Protestant or Catholic).

- But white Christians were a rapidly diminishing share of the American electorate

- White Christians declined from three-quarters of the electorate in the 1990s to barely half the electorate in the 2010s.

- As Republican Lindsey Graham put it in 2012, “We’re not generating enough angry white guys to stay in business for the long term.”

- The GOP remained an overwhelmingly white Christian party.

- An Omen: the Fate of the California Republican Party, Page 104

- In the early 1990s, with the economy in recession, the Republican governor, Pete Wilson, who aspired to reelection in 1994, found himself trailing badly in the polls. To regain his standing, Wilson appealed to growing resentment among California’s declining white majority. Because whites still constituted 80 percent of the state’s electorate at the time, dwarfing the Latino vote (8 percent of the electorate), an anti-immigrant stance seemed like a good political bet. So Wilson turned hard to the right and embraced Proposition 187, a ballot initiative that would restrict undocumented immigrants’ access to education and health care and require teachers, doctors, and nurses to report anyone suspected of being undocumented to the authorities.

- By 2000, a majority of Californians were nonwhite, and by 2021 about 60 percent of California voters were nonwhite. Having alienated this emerging majority for short-term electoral gain, Republicans suffered a political collapse of historic proportions.

Obama’s Presidency and Since

- Obama elected president in 2008

- Obama’s presidency made the transition to multiracial democracy plain for all Americans to see.

- On election night in 2012, the Fox News host Bill O’Reilly declared that “the white establishment is now the minority…. It’s not traditional America anymore.” The following day, Rush Limbaugh told his listeners, “I went to bed last night thinking we’re outnumbered…. I went to bed… thinking we’ve lost the country.”

- Beginning of the Tea Party Movement, 2009, Page 114

- Surveys showed Tea Party members to be overwhelmingly anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, and resistant to ethnic and cultural diversity. According to the political scientists Christopher Parker and Matt Barreto, Tea Partiers perceived themselves to be “losing their country to groups they fail to recognize as ‘real’ Americans.”

- Voter ID Laws, Page 108

- Prior to 2005, no U.S. state required photo identification to vote, and prior to 2011 only Georgia and Indiana did so. But between 2011 and 2016, thirteen states—all Republican led—passed strict photo ID laws. The laws were adopted on seemingly reasonable grounds: combating voter impersonation fraud. But there were two problems.

- Election fraud—especially voter impersonation fraud—is virtually nonexistent in the United States.

- Voter ID laws are biased against poor and minorities

- Prior to 2005, no U.S. state required photo identification to vote, and prior to 2011 only Georgia and Indiana did so. But between 2011 and 2016, thirteen states—all Republican led—passed strict photo ID laws. The laws were adopted on seemingly reasonable grounds: combating voter impersonation fraud. But there were two problems.

- In 2012, Black turnout exceeded white turnout for the first time in U.S. history.

- GOP Attempt to Broaden the Republican Electorate, Page 107

- In the wake of Barack Obama’s 2012 reelection RNC chair, Reince Priebus, launched what he proclaimed to be “the most comprehensive election review” ever undertaken after a party’s defeat. The review’s final report, known as the RNC “autopsy,” sharply critiqued the GOP’s focus on white voters, warning that the party was “marginalizing itself” by “not working beyond its core constituencies.”

- wikipedia.org/wiki/Growth_%26_Opportunity_Project

- Trump tapped into white fear and resentment

- A 2021 survey found that 84 percent of Trump voters said they “worry that discrimination against whites will increase significantly in the next few years.” Many Trump supporters also embraced the “great replacement theory,” which claimed that a cabal of elites was using immigration to replace America’s “native” white population.

- The most influential peddler of the “great replacement theory” was Tucker Carlson

- A 2021 survey sponsored by the American Enterprise Institute found that 56 percent of Republicans agreed with the statement that “the traditional American way of life is disappearing so fast that we may have to use force to save it.”

- A 2021 survey found that 84 percent of Trump voters said they “worry that discrimination against whites will increase significantly in the next few years.” Many Trump supporters also embraced the “great replacement theory,” which claimed that a cabal of elites was using immigration to replace America’s “native” white population.

Chapter 5 Fettered Majorities

Tyranny of the Majority

- In a democracy two domains must be protected from majorities.

- Civil Liberties

- This includes the basic individual rights that are necessary for any democracy, such as freedom of speech, press, association, and assembly.

- But it also includes a range of other domains in which our individual life choices should be free from the interference of elected governments or legislative majorities. Elected governments, for example, should not have the power to determine whether or how we worship; they should not decide what books we may read, what movies we may watch, or what may be taught in universities; and they shouldn’t decide the race or gender of the people we marry.

- Example: Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940) Page 138

- In an 8-to-1 decision, the Court upheld a Board of Education rule that required school children to salute the flag as part of their daily routine.

- But in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943) the Court reversed its decision, ruling that national symbols like the flag do not trump the right to free speech.

- Rules of Democracy Itself

- Elected governments must not be able to use their temporary majorities to entrench themselves in power by changing the rules of the game in ways that weaken their opponents or undermine fair competition. This is the specter of “majority tyranny”: the possibility that a government will use its popular or parliamentary majority to vote the opposition—and democracy—out of existence.

- Example: Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Page 60

- Example: Tanzania 1962, Page 140

Tyranny of the Minority

- Most democrats agree that individual liberties and the opposition’s right to fair competition must be placed beyond the reach of majorities. All democracies must therefore be tempered by a degree of counter-majoritarianism. But democracies must also empower majorities. Indeed, a political system that does not grant majorities considerable say cannot be called a democracy. This is the danger of counter-majoritarianism: rules designed to fetter majorities may allow partisan minorities to consistently thwart and even rule over majorities. As the eminent democratic theorist Robert Dahl warned, fear of “tyranny of the majority” may obscure an equally dangerous phenomenon: tyranny of the minority. So just as it is essential that some domains be placed beyond the reach of majorities, so too is it essential that other domains remain within the reach of majorities. Democracy is more than majority rule, but without majority rule there is no democracy.

- merriam-webster.com/dictionary/majoritarianism

- the philosophy or practice according to which decisions of an organized group should be made by a numerical majority of its members

- An institution is counter-majoritarian if it can impede or block a majority of voters from electing officials that enact legislation they want.

Principles of Democratic Rule

- Those with more votes should prevail over those with fewer votes in determining who holds political office.

- There is no theory of liberal democracy that justifies any other outcome. When candidates or parties can win power against the wishes of the majority, democracy loses its meaning.

- Those who win elections should govern

- Legislative majorities should be able to pass regular laws—provided, of course, that such laws do not violate civil liberties or undermine the democratic process. From a democratic standpoint, supermajority rules that allow a parliamentary minority to permanently block regular, lawful legislation backed by the majority are difficult to defend.

Counter-Majoritarian Institutions in the U.S.

- Bill of Rights, which protect certain actions against the majority making them a crime.

- The Supreme Court, with power of judicial review and lifetime appointments for justices.

- Federalism, which devolves considerable lawmaking power to state and local governments beyond the reach of national majorities.

- A bicameral Congress, which means that two legislative majorities are required to pass laws.

- A severely malapportioned Senate, in which all states are given the same representation regardless of population.

- The filibuster, a supermajority rule in the Senate (not in the Constitution) that allows a partisan minority to permanently block legislation backed by the majority.

- The Electoral College, an indirect system of electing presidents that privileges smaller states and allows losers of the popular vote to win the presidency.

- Extreme supermajority rules for constitutional change, requiring a two-thirds vote of each house of Congress plus approval by three-quarters of U.S. states.

A Constitution Extremely Difficult to Amend, Page 145-146

- Since constitutions may endure for decades and even centuries, one generation inevitably ties the hands of majorities generations into the future. Legal theorists have called this the problem of the dead hand. The more difficult a constitution is to change, the firmer the grip of the dead hand.

- “The dead,” Jefferson wrote to Madison, “should not govern the living.”

- On the other hand, as Madison argued, it’s important that constitutions not be too easy to change.

- For example, Bolivia and Ecuador have changed constitutions at a rate of about once a decade since independence in the 1820s. They have never sustained stable democracies, showing us the cost of not having a set of widely accepted rules that transcend politics.

Malapportioned Senate, Page 154-156

- At the Constitutional Convention, larger states wanted congressional representation based on population while states with smaller populations wanted every state to have equal representation.

- The solution was the Connecticut Compromise: the House of Representatives would be elected via a majoritarian principle, with representation proportional to the population of the state, but the Senate would be composed of two senators per state, no matter the size.

- Many of the founders, including Hamilton and Madison, strongly opposed the idea of equal representation of states.

- As Hamilton argued at the convention, people, not territories, deserved representation in Congress:

- “As states are a collection of individual men, which ought we to respect most: the rights of the people composing them, or the artificial beings resulting from the composition? Nothing could be more preposterous or absurd than to sacrifice the former to the latter.”

- avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_629.asp (CC: Friday June 29, 1787)

- “As states are a collection of individual men, which ought we to respect most: the rights of the people composing them, or the artificial beings resulting from the composition? Nothing could be more preposterous or absurd than to sacrifice the former to the latter.”

- Criticizing the Articles of Confederation, Hamilton also argued that the equal representation of states “contradicts that fundamental maxim of republican government, which requires that the sense of the majority should prevail.” “It may happen,” he wrote in Federalist No. 22, that a “majority of states is a small minority of the people of America.”

- avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed22.asp (Federalist Paper 22)

- ” It may happen that this majority of States is a small minority of the people of America”

- constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/historic-document-library/detail/articles-of-confederation

- The Articles created a national government centered on the legislative branch, which was comprised of a single house. There was no separate executive branch or judicial branch. The delegates in Congress voted by state—with each state receiving one vote, regardless of its population.

- avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed22.asp (Federalist Paper 22)

- Madison described equal representation in the Senate as “evidently unjust” and warned that it would allow small states to “extort measures [from the House] repugnant to the wishes and interests of the majority.”

- avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_630.asp (CC: Saturday June 30, 1787)

- James Wilson of Pennsylvania also rejected equal state representation, asking, like Hamilton, “Can we forget for whom we are forming a government? Is it for men, or for the imaginary beings called states?”

- avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_630.asp (CC: Saturday June 30, 1787)

- As Hamilton argued at the convention, people, not territories, deserved representation in Congress:

Electoral College, Pages 156 -158

- The delegates debated how the president should be chosen for twenty-one days and held thirty separate votes—more than for any other issue.

- The initial draft proposal, backed by Madison, called for Congress to choose the president. But many delegates feared the president would be overly beholden to Congress, so the system was rejected.

- britannica.com/topic/parliamentary-system

- a democratic form of government in which the party (or a coalition of parties) with the greatest representation in the parliament (legislature) forms the government, its leader becoming prime minister or chancellor. Executive functions are exercised by members of the parliament appointed by the prime minister to the cabinet.

- britannica.com/topic/parliamentary-system

- James Wilson argued for popular election of the president. But most delegates were still too distrustful of the “people” to accept direct elections, and the proposal was twice voted down by the convention.

- Southern delegates were particularly opposed to direct presidential elections. As Madison recognized, the South’s heavy suffrage restrictions, including the disenfranchisement of the enslaved population, left it with many fewer eligible voters than the North.

- The Committee on Unfinished Parts proposed a model that had been used to “elect” monarchs and emperors under the Holy Roman Empire. When the emperor died, local princes and archbishops gathered in a Council of Electors to vote on a new emperor. Even today, with the passing of a pope, the Sacred College of Cardinals convenes in Rome to “elect a successor.”

- Madison personally viewed direct elections as the “fittest” method to choose a president, but he ultimately recognized that the Electoral College generated the “fewest objections,” largely because it provided additional advantages to both the southern slave states and the small states. The number of electoral votes assigned to each state would be equal to that state’s House delegation plus its two senators.

- This arrangement satisfied the southern states because House representatives would be elected under the three-fifths clause.

- It satisfied the small states because the Senate was based on equal state representation

- In this way, both sets of states had a greater say in the selection of the president than they would have had in a system of direct popular election.

- The Electoral College never did what it was designed to do. Hamilton expected it to be composed of highly qualified notables, or prominent elites, chosen by state legislatures, who would act independently. This proved illusory. The Electoral College immediately became an arena of party competition. As early as 1796, electors acted as strictly partisan representatives.

Supreme Court, Pages 158-160

- The Constitution (Article III) required that Congress create a Supreme Court, which it did in the First Congress in 1789. The Constitution also explicitly stated that federal judges could enjoy lifetime tenure (conditional on “good behavior”).

- The framers were not concerned about long tenures on the court.

- Life expectancy was shorter at the time of the founding

- The position of Supreme Court justice lacked the status and appeal that it has today.

- The powers of the Supreme Court were left rather vague.

- The framers clearly aimed to establish the supremacy of federal law over state law (something that was lacking in the ill-fated Articles of Confederation),

- But the idea of judicial review of federal legislation was never resolved in the convention or explicitly incorporated into the Constitution.

- britannica.com/topic/judicial-review

- the power of the courts of a country to examine the actions of the legislative, executive, and administrative arms of the government and to determine whether such actions are consistent with the constitution. Actions judged inconsistent are declared unconstitutional and, therefore, null and void.

- britannica.com/topic/judicial-review

- Judicial review emerged gradually, not by design but in judicial practice during the 1790s and early years of the nineteenth century.

- In Marbury v. Madison (1803), the Supreme Court for the first time ruled an act of Congress inconsistent with the Constitution and therefore null and void.

- Specifically Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789

- Chief Justice John Marshall wrote the the court’s opinion.

- britannica.com/event/Marbury-v-Madison

Senate Filibuster, Pages 160-163

- The original Senate had no filibuster. Rather, it adopted the so-called previous question motion, which allowed a simple majority of senators to vote to end debate. The rule was little used, however, and in 1806, following recommendations by the former vice president Aaron Burr, the Senate eliminated it.

- There were no organized filibusters until the 1830s (or by some accounts, 1841), and the practice was so rare that it didn’t even have a name until the 1850s.

- Filibuster use picked up in the late nineteenth century.

- So in 1917, the Senate passed Rule 22, under which a vote of two-thirds of senators could end debate (a practice known as cloture) and force a vote on legislation.

- In 1975, the Senate reduced the number of votes required for cloture from 67 to 60.

- Still, filibusters remained relatively rare for much of the twentieth century—in part because they were hard work. Senators had to physically hold the floor—by speaking continuously—to sustain a filibuster.

- After reforms in the 1970s, senators only needed to signal their intent to filibuster to party leaders—via a phone call or, today, an email—to put the supermajority rule in effect. As filibustering became costless, what had once been rare became a routine practice. In other words, the filibuster evolved into what was effectively a supermajority rule for all Senate legislation.

- Many of the framers of the Constitution, including Hamilton and Madison, strongly opposed supermajority rules in Congress.

- In Federalist No 58, Madison explicitly rejected the use of supermajority rules in Congress on the grounds that “the fundamental principle of free government would be reversed. It would no longer be the majority that would rule; the power would be transferred to the minority.”

- avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed58.asp (Federalist Paper 58)

- Hamilton argued (in Federalist No. 22) that a supermajority rule would “subject the sense of the greater number to that of the lesser number.” Under such rules, he observed,

- “We are apt to rest satisfied that all is safe, because nothing improper will likely to be done; but we forget how much good may be prevented, and how much ill may be produced, by the power of hindering that which is necessary from being done, and of keeping affairs in the same unfavorable posture in which they may happen to stand at particular periods.”

- avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed22.asp (Federalist Paper 22)

- “We are apt to rest satisfied that all is safe, because nothing improper will likely to be done; but we forget how much good may be prevented, and how much ill may be produced, by the power of hindering that which is necessary from being done, and of keeping affairs in the same unfavorable posture in which they may happen to stand at particular periods.”

- In Federalist No 58, Madison explicitly rejected the use of supermajority rules in Congress on the grounds that “the fundamental principle of free government would be reversed. It would no longer be the majority that would rule; the power would be transferred to the minority.”

- With the exception of treaty ratification and the removal of impeached officials, the Philadelphia Convention rejected all proposals for supermajority rules in regular congressional legislation.

Chapter 6 Minority Rule

How the Constitution Developed a Partisan Bias

- The U.S. system has always contained institutions that empower minorities at the expense of majorities. But only in the twenty-first century has counter-majoritarianism taken on a partisan cast—that is, regularly benefiting one party over another in national politics.

- Two things changed over time.

- First, as the country expanded and America’s population grew, the asymmetry between low- and high-population states increased dramatically.

- In 1790, a voter in Delaware (the least populous state) had about thirteen times more influence in the U.S. Senate than a voter in the most populous state, Virginia. In 2000, by contrast, a voter in Wyoming has nearly seventy times more influence in the U.S. Senate than a voter in California.

- But there was another change: America urbanized.

- At the time of the founding, the United States was overwhelmingly a country of small towns and vast expanses of sparsely populated farmlands and forests. All states—large and small—were rural. As America industrialized during the nineteenth century, however, people flocked to urban areas in search of work. In 1920, the U.S. Census Bureau announced, to great public fanfare, that for the first time in U.S. history more Americans lived in cities than in the countryside.

- First, as the country expanded and America’s population grew, the asymmetry between low- and high-population states increased dramatically.

- What began as a strictly small-state bias had become a rural-state bias.

- This meant that rural jurisdictions were now overrepresented in three of America’s most important national political institutions: the U.S. Senate, the Electoral College, and—because presidents nominate Supreme Court justices and the Senate confirms them—the Supreme Court.

- Even though America’s constitutional system favored rural interests for much of the twentieth century, however, it had no clear-cut partisan bias. This is because for most of the twentieth century both parties had urban and rural bases.

- The Constitution’s small-state bias, which became a rural bias in the twentieth century, has become a partisan bias in the twenty-first century.

- Left-of-center parties—the Labour Party in Great Britain, the Social Democrats and Greens in Germany, the Democrats in the United States—have increasingly become the home of urban voters, who tend to be more secular, cosmopolitan, and tolerant of ethnic diversity, whereas right-leaning—and often far-right-wing—parties increasingly represent small-town and rural voters, who tend to be more socially conservative and less supportive of immigration and ethnic diversity.

- In the United States, this shift was exacerbated by the race-driven transformation of the party system. Before the civil rights movement rural voters in the South were overwhelmingly Democratic. Elsewhere, they leaned Republican. After the civil rights revolution, the (white) rural South gradually moved into the Republican camp.

- Today, then, Republicans are predominantly the party of sparsely populated regions, while Democrats are the party of the cities. As a result, the Constitution’s small-state bias, which became a rural bias in the twentieth century, has become a partisan bias in the twenty-first century.

- Analogy

- In U.S. professional basketball, teams score one point for a free throw, two points for a regular shot, and three points for a shot from beyond the three-point line. But imagine a game in which those rules apply only to one team (call it Team Normal), and the other team (Team Extra) is given four points for each shot it makes beyond the three-point line.

- America risks descending into minority rule—an unusual and undemocratic situation in which a party that wins fewer votes than its rivals nevertheless maintains control over key levers of political power.

Republican Advantages

- House

- Efficiency of Distribution of Votes across Congressional Districts favors GOP

- In House elections, the proportion of seats a party wins depends not only on the proportion of votes it receives but also on how “efficiently” its votes are distributed across electoral districts. The GOP’s vote distribution has been more efficient than the Democrats’.

- For example, in the 2012 House election, Democrats received more votes than Republicans but won only 201 seats, versus 234 for the GOP. (Wikipedia)

- View House Elections from 2000 to 2022

- Efficiency of Distribution of Votes across Congressional Districts favors GOP

- Senate

- Senate’s small-state bias favors GOP

- At no time during the twenty-first century have Senate Republicans represented a majority of the U.S. population. Based on states’ populations, Senate Democrats have continuously represented more Americans since 1999.

- For example:

- Electoral College

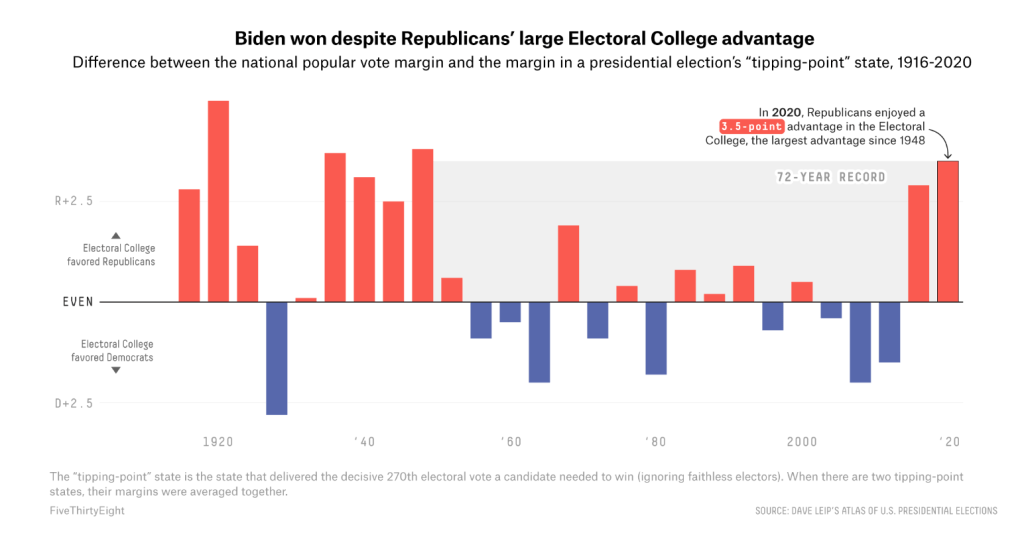

- Efficiency of Vote Distribution favors GOP

- Winner-take-all electoral votes amplifies the effect of GOP’s more efficient distribution.

- Slight GOP small-state bias

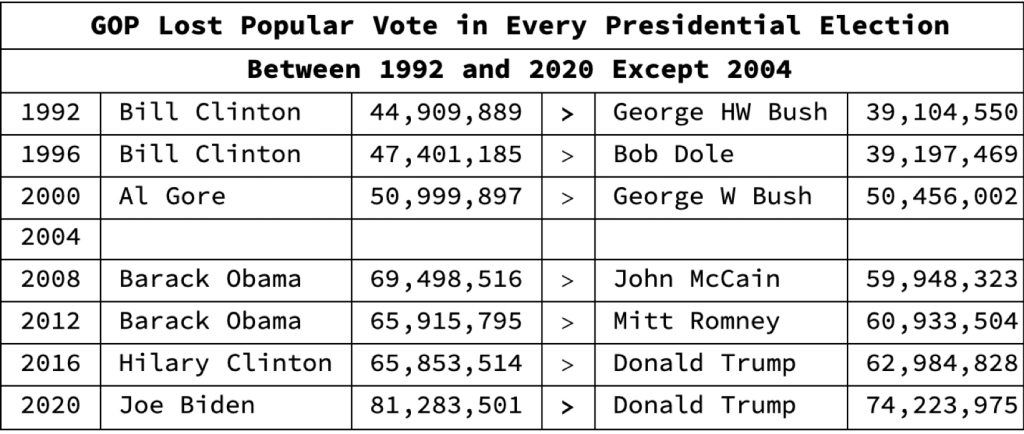

- GOP lost the popular vote in every presidential election between 1992 and 2020 except 2004.

- Supreme Court

- Given the nature of the Electoral College and the Senate, Supreme Court justices may be nominated by presidents who lost the popular vote and confirmed by Senate majorities that represent only a minority of Americans. And given the Republican advantage in the Electoral College and the Senate, such justices are more likely to be Republican appointees.

- Four of nine current Supreme Court justices—Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett—were confirmed by a Senate majority that collectively won a minority of the popular vote in Senate elections and represented less than half of the American population. And three of them—Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Coney Barrett—were also nominated by a president who lost the popular vote

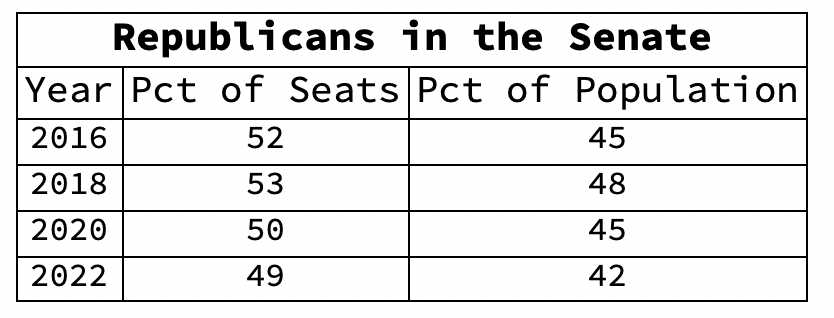

Republican Advantage in the Senate

- Sparsely populated states representing less than 20 percent of the U.S. population can produce a Senate majority. And states representing 11 percent of the population can produce enough votes to block legislation via a filibuster. The problem is now compounded by partisan bias. The GOP’s dominance in low-population states allows it to control the U.S. Senate without winning national popular majorities.

- At no time during the twenty-first century have Senate Republicans represented a majority of the U.S. population. Based on states’ populations, Senate Democrats have continuously represented more Americans since 1999.

- For example:

- For example:

- Tipping Point Argument