Back to Quantum Mechanics

Contents

Entangled Coins

- Suppose a scientist creates an “entanglement” box — two coins are put in the box for 10 seconds and the next time they are flipped the coins are guaranteed to land one heads and the other tails. You test the entanglement box with a quarter and nickel. In a hundred entangled flips

- the quarter lands heads and the nickel lands tails about half the time,

- the quarter lands tails and the nickel lands heads about half the time.

- For some of the flips the coins are in different cities, thousands of miles apart.

- You also flip the coins when they are not entangled and the results are what you would expect:

- two heads about 25% of the time,

- two tails about 25% of the time,

- the quarter heads and the nickel tails about 25% of the time,

- the quarter tails and the nickel heads about 25% of the time.

- Two hypotheses that (sort of) explain what’s going on:

- Hidden Variable Hypothesis

- The entanglement box (randomly) sets some unknown property of the coins that predetermines whether it lands heads or tails. So on some occasions the quarter is predetermined to land heads and the nickel tails. On other occasions the quarter is predetermined to land tails and the nickel heads.

- Action-at-a-Distance Hypothesis

- The entanglement box modifies the coins so that the first coin flipped alters the state of the other coin so it can’t have the same outcome. The quarter landing heads, for example, puts the nickel into a state such that, when flipped, it lands tails.

- Hidden Variable Hypothesis

Entangled Electrons

Scenario

- The spins of two electrons are entangled in what’s called a singlet state. Without affecting their spins, the electrons are transported across the country, one to New York, the other to California. Alice measures the spin of the New York electron, which is equally likely to be spin-up and spin-down. Suppose she finds the spin of her electron to be spin-up. At that point, QM predicts, with probability 1, that Bob will find the spin of his electron to be spin-down. Similarly, if Alice finds the spin of her electron to be spin-down, QM predicts, with probability 1, that Bob will find the spin of his electron to be spin-up.

Alice’s Operator

- Alice’s measurement of the vertical spin of her electron is represented by an operator whose eigenvectors and eigenvalues are:

- Eigenvector |updn> with eigenvalue +1 (spin-up for Alice’s electron)

- Eigenvector |dnup> with eigenvalue -1 (spin-down for Alice’s electron)

- If the electrons are entangled in the singlet state and Alice measures the vertical spin of her electron, then:

- the |singlet> state collapses into |updn> with probability 1/2.

- the |singlet> state collapses into |dnup> with probability 1/2.

Bob’s Operator

- Bob’s measurement of the vertical spin of his electron is represented by an operator whose eigenvectors and eigenvalues are:

- Eigenvector |updn> with eigenvalue -1 (spin-down for Bob’s electron)

- Eigenvector |dnup> with eigenvalue +1 (spin-up for Bob’s electron)

- If the electrons are entangled in the singlet state and Bob measures the vertical spin of his electron, then:

- the |singlet> state collapses into |updn> with probability 1/2.

- the |singlet> state collapses into |dnup> with probability 1/2.

Alice and Bob’s Measurements

Alice Measures her Electron First

- Suppose the electrons are in the singlet state and Alice measures the vertical spin of her electron and finds it to be +1 (spin-up for her electron). As a result, per QM’s Collapse Postulate, the |singlet> state of the system collapses into |updn>. Thus, when Bob measures the vertical spin of his electron, QM predicts, with probability 1, that the outcome of his measurement is -1 (spin-down for his electron).

- The probability of |updn> collapsing into |updn> = 1

- |updn> is an eigenvector of Bob’s operator with eigenvalue -1

- Similarly, if Alice finds the spin of her election to be -1 (spin-down for her electron), the state of the system after her measurement is |dnup> and, with probability 1, Bob will find the spin of his electron to be +1 (spin-up for his electron).

- The probability of |dnup> collapsing into |dnup> = 1

- |dnup> is an eigenvector of Bob’s operator with eigenvalue +1

Bob Measures his Electron First

- Suppose the electrons are in the singlet state and Bob measures the vertical spin of his electron and finds it to be +1 (spin-up for his electron). As a result, per QM’s Collapse Postulate, the |singlet> state of the system collapses into |dnup>. Thus, when Alice measures the vertical spin of her electron, QM predicts, with probability 1, that the outcome of her measurement is -1 (spin-down for her electron).

- The probability of |dnup> collapsing into |dnup> = 1

- |dnup> is an eigenvector of Alice’s operator with eigenvalue -1

- Similarly, if Bob finds the spin of his election to be -1 (spin-down for his electron), the state of the system after his measurement is |updn> and, with probability 1, Alice will find the spin of her electron to be +1 (spin-up for her electron).

- The probability of |updn> collapsing into |updn> = 1

- |updn> is an eigenvector of Alice’s operator with eigenvalue +1

Hypotheses

- Hidden Variable Hypothesis

- The entanglement process (randomly) sets the vertical spin of one electron to +1 (spin-up) and the vertical spin of the other electron to -1 (spin-down). So the spins of the electrons are predetermined to be opposite.

- Action-at-a-Distance Hypothesis

- A measurement by either Alice or Bob results in the instant collapse of the entangled electrons into a state such that, if Alice and Bob measure the spins of their electrons, then, with probability 1, their outcomes will be opposite.

EPR Argument

- In a classic paper published in 1935, Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen used entanglement to argue that Quantum Mechanics is incomplete, failing to account for all quantum phenomena.

- Here’s a paraphrase of their argument:

- The entanglement of the spin of two elections means that either (a) the electrons have fixed and opposite values of spin when they’re entangled (and before their spins are measured) or (b) the outcome of measuring the spin of one electron determines the outcome of measuring the spin of the other (instantaneously, even over vast distances).

- Physical interactions can’t happen faster than the speed of light. This rules out (b).

- See Locality below.

- Therefore (a) is true.

- If (a) is true, Quantum Mechanics is incomplete because it fails to account for the fact that electrons have determinate values of spin before they are measured.

- Therefore Quantum Mechanics is incomplete.

Locality

- Principle of Locality (aka No Action at a Distance)

- One event can affect (influence) another event only through an intermediate process that takes place between them.

- Thus, the Sun’s gravitational pull on Earth happens though gravity waves traveling at the speed light.

- Corollary

- No event can affect (influence) another event faster than the speed of light, per Special Relativity.

- Which implies: no instantaneous action at a distance.

- QM seems to violate the Principle of Locality in that a measurement can instantly change the probability of a particular outcome of a distant measurement, e.g. from 1/2 to 1.

Mathematics of Entanglement

State Vectors

- The state vector for the entangled electrons is what’s called the singlet state

- |singlet> = {0, 1/√2, -1/√2, 0}.

- State vector |updn> = {0, 1, 0, 0}

- If the state of the system = |updn> and Alice measures the vertical spin of her electron, the outcome of her measurement = +1 (spin-up) with probability 1.

- If the state of the system = |updn> and Bob measures the vertical spin of his electron, the outcome of his measurement = -1 (spin-down) with probability 1.

- State vector |dnup> = {0, 0, 1, 0}

- If the state of the system = |dnup> and Alice measures the vertical spin of her electron, the outcome of her measurement = -1 (spin-down) with probability 1.

- If the state of the system = |dnup> and Bob measures the vertical spin of his electron, the outcome of his measurement = +1 (spin-up) with probability 1.

Operators

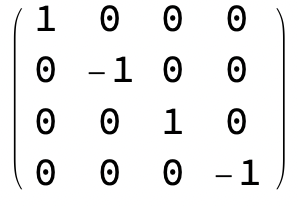

- Alice’s measurement of the vertical spin of her electron is represented by the operator:

- The eigenvectors and eigenvalues of Alice’s operator are:

- Eigenvector |updn> with eigenvalue +1 (spin-up for Alice’s electron)

- Eigenvector |dnup> with eigenvalue -1 (spin-down for Alice’s electron)

- Bob’s measurement of his electron is represented by the operator:

- The eigenvectors and eigenvalues of Bob’s operator are:

- Eigenvector |updn> with eigenvalue -1 (spin-down for Bob’s electron)

- Eigenvector |dnup> with eigenvalue +1 (spin-up for Bob’s electron)

Probabilities of Collapse

- The probability of |singlet> collapsing into |updn> = 1/2

- |<singlet|updn>|2 = 1/2

- The probability of |singlet> collapsing into |dnup> = 1/2

- |<singlet|dnup>|2 = 1/2

- The probability of |updn> collapsing into |updn> = 1

- |<updn|updn>|2 = 1

- The probability of |dnup> collapsing into |dnup> = 1

- |<dnup|dnup>|2 = 1

- The probability of |updn> collapsing into |dnup> = 0

- |<updn|dnup>|2 = 0

- The probability of |dnup> co

- |<dnup|updn>|2 = 0

Sundry Calculations in Mathematica

- |dnup> is an eigenvector of Alice’s operator with eigenvalue -1

- Alice’s operator = {{1,0,0,0},{0,1,0,0},{0,0,-1,0},{0,0,0,-1}}

- |dnup> = {0,0,1,0}

- Dot[{{1,0,0,0}, {0,1,0,0}, {0,0,-1,0}, {0,0,0,-1}}, {0,0,1,0}] = {0,0,-1,0}

- -1 {0,0,1,0} = {0,0,-1,0}

- So the dot product Alice’s operator · |dnup> = -1 |dnup>, which makes |dnup> an eigenvector of Alice’s operator with eigenvalue -1.

- The probability of |singlet> collapsing into |dnup> = 1/2

- |singlet> = {0, 1/Sqrt[2], -(1/Sqrt[2]), 0}

- |dnup> = {0, 0, 1, 0}

- Abs[Dot[Conjugate[|singlet>], |dnup>]]2 = 1/2

- Conjugate[ {0, 1/Sqrt[2], -(1/Sqrt[2]), 0}] = {0, 1/Sqrt[2], -(1/Sqrt[2]), 0}

- Dot[Conjugate[ {0, 1/Sqrt[2], -(1/Sqrt[2]), 0}], {0, 0, 1, 0}] = -(1/Sqrt[2])

- Abs[Dot[Conjugate[ {0, 1/Sqrt[2], -(1/Sqrt[2]), 0}], {0, 0, 1, 0}]] = 1/Sqrt[2]

- Abs[Dot[Conjugate[ {0, 1/Sqrt[2], -(1/Sqrt[2]), 0}], {0, 0, 1, 0}]]^2 = 1/2