A fallacy is an error in reasoning having an air of plausibility

Outline

Fallacies

- A fallacy is an error in reasoning having an air of plausibility.

- They arise in the contexts of:

- inference and reasoning

- argumentation and debate

- attempts to persuade

- Hundreds of fallacies have been catalogued since Aristotle.

- The fallacies on this page are some of the most well known.

- There are different classifications of fallacies, e.g. formal, informal, material, relevance, ambiguity, illegitimate presumption, and verbal. The fallacies here are classified into deductive and evidential.

- Akin to fallacies (and sometimes so classified) are:

Deductive Fallacies

- A deductive fallacy is an invalid form of deductive argument that seems valid.

- A deductive argument is an argument whose conclusion (purportedly) follows necessarily from its premises.

- A deductive argument is valid if it’s logically impossible that its premises are true and conclusion false.

- Affirming the Consequent

- Denying the Antecedent

- Composition

- Division

- Ecological Fallacy

- Equivocation

- Gambler’s Fallacy

- Hypothetical Syllogism (Material Implication)

- Intensional Fallacy

- Lottery Fallacy

- Simpson’s Paradox

Evidential Fallacies

- An evidential fallacy is a form of evidential argument that fails because of defective or insufficient evidence.

- An evidential argument is an argument whose premises are evidence (purportedly) making its conclusion probable.

- Defective Evidence

- Insufficient Evidence

The Fallacies, in Alphabetic Order

Affirming the Consequent

- Affirming the Consequent is an inference of the form:

- If A, then C

- C

- Therefore A

- The conditional if A then C consists of the antecedent A and the consequent C. The second premise of Affirming the Consequent affirms the consequent C.

- The argument-form is invalid, per logical analogy:

- If Matt Damon is over seven feet, he’s over five feet.

- Damon is over five feet.

- Therefore, he’s over seven feet.

- See Affirming the Consequent, Denying the Antecedent, Modus Ponens, Modus Tollens

Appeal to Consequences

- Appeal to Consequences is arguing that a claim should be accepted or rejected based on the desirable or undesirable consequences of believing it.

- Example

- If you don’t accept Jesus Christ as your lord and savior, you’ll be damned for all eternity.

Argument from Ignorance

- Argument from Ignorance is arguing that something is true because it’s not disproven or that something is false because it’s not proven.

- Sir Martin Rees: “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

- Examples

- There must be some truth to astrology since for thousands of years no one has succeeded in disproving it.

- OJ Simpson did not kill Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman since he was not proven guilty in a court of law.

Begging the Question (Circular Reasoning)

- Begging the Question is known as “assuming that which is to be proved.”

- An argument begs the question if one of its premises

- presupposes that the argument’s conclusion is true

- is not supported by further premises

- is an essential part of the argument.

- Example

- Dialogue:

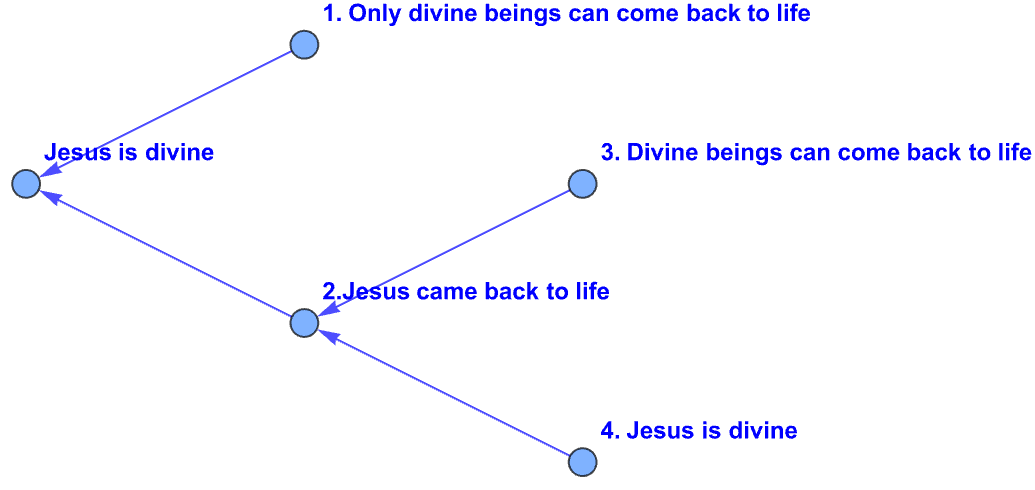

- Believer: I know Jesus is divine because he returned from the dead and only divine beings come back from the dead.

- Skeptic: How do you know Jesus came back from the dead?

- Believer: Because Jesus was not an ordinary human being – he was the Son of God.

- The Believer first presents the argument:

- Only divine beings can come back to life.

- Jesus came back to life.

- Therefore, Jesus was divine.

- Replying to the Skeptic, the Believer presents a second argument:

- Divine beings can come back to life.

- Jesus was divine.

- Therefore, Jesus was able to come back to life.

- The Believer’s argument and reply can be combined and depicted as a tree, where the arrow means “is established by.”

- The combined argument begs the question because:

- premise (4) presupposes that the conclusion is true

- premise (4) is not established by further premises

- i.e. no arrows point to node 4

- the conclusion is not established by other premises of the argument

- i.e. the tree resulting from removing node 4 does not establish the conclusion.

- Dialogue:

- Clause 2 is needed because some sound arguments have premises that presuppose their conclusions. For example:

- Though premise 1 presupposes that there was a coyote in the backyard, the argument does not beg the question since premise 1 supported by further premises 2 and 3.

- The argument that Jesus is divine not only begs the question but is also circular, since the conclusion is also one of the premises.

Biased Sample / Selection Bias

- Selection Bias is a flaw in the procedure for drawing a sample from a population that results in a difference between (1) the probability of selecting an individual having a certain attribute and (2) the proportion of the population with that attribute. The resulting sample is thus a biased representation of the population.

- The Fallacy of Biased Sample is generalizing from the biased sample to the population as a whole.

- The classic example:

- The Literary Digest magazine conducted a poll to determine the likely winner of the 1936 presidential election between Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Alf Landon, Governor of Kansas. Questionnaires were mailed to 10 million people, the names obtained from telephone books, automobile registrations, and the magazine’s readership. 2.4 million people responded. (The number of respondents in a typical national election poll is in the thousands.) 43% said they planned to vote for Roosevelt. The magazine predicted a landslide for Landon.

- Roosevelt won all but two states.

- The Literary Digest’s poll was biased against those without phones and automobiles, mostly Democrats.

- It is also thought that anti-Roosevelt sentiment was strong among Landon supporters, making it more likely they would take the time to mail back a response.

Base Rate Fallacy

- The Base Rate Fallacy is an inference from a rate or proportion that ignores a background rate or proportion, called the base rate.

- Example 1

- Fallacious Argument

- Joe is given a random drug test that’s 95 percent reliable, meaning 95 percent of drug users test positive and 95 percent of non-drug users test negative. Five percent of the population takes drugs.

- He tests positive.

- Therefore, the probability Joe is a drug user is 95 percent.

- The Problem

- The probability that Joe is a drug user is not 95 percent. The calculation is wrong because it ignores the base rate of five percent of the population taking drugs.

- When the base rate is factored into the calculation, the probability Joe is a user drops to 50 percent.

- See Random Drug Test for details.

- Fallacious Argument

- Example 2

- Fallacious Argument

- After taxes were cut at the beginning of 2017, tax revenues increased from 3.2 trillion in 2017 to 3.3 trillion in 2018

- By bringing in more tax revenue than the preceding year, therefore, the tax cuts paid for themselves in 2018.

- The Problem

- But tax revenues were on track to be higher in 2018 than in 2017 without the tax cuts. Indeed, the CBO had predicted 3.5 trillion for 2018. So the 2018 tax revenues were less than they would have been without the tax cuts, by $200 billion. The 2017 tax cuts thus did not pay for themselves in 2018. The argument ignores the base rate of 10% that tax revenues were increasing before the tax cuts.

- See Right and Wrong Baselines for details.

- Fallacious Argument

Composition

- The first form of Composition is inferring that what’s true individually of a group’s members is thereby true of the group collectively.

- Example

- A car emits less toxic waste than a bus.

- Therefore cars emit less toxic waste than buses.

- Example

- The second form of Composition is inferring that what’s true of the entities making up a thing is thereby true of the thing itself

- Example

- What appears to be a “red” wheelbarrow really has no color because it’s made up of colorless atoms.

- Example

Cum Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc

- Cum Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc (“with this therefore because of this”) is inferring that a causal connection exists between two phenomena merely because of a statistical correlation between them.

- Example

- The Pearson correlation coefficient is a number between -1 and +1 calculated from two sets of paired numbers. For example, the correlation coefficient between the series {1, 2, 3, 4, 3, 2, 1} and {2, 5, 7, 9, 8, 6, 4} is 0.94992, a high correlation.

- Suppose the first series, {1, 2, 3, 4, 3, 2, 1}, is the number of times Joe in New York sneezed each day Monday through Sunday and the second series, {2, 5, 7, 9, 8, 6, 4}, is the number of times Bill in Texas cursed each day of the same week. The high correlation is no evidence of a causal connection.

- Inferring a causal connection requires more than mere statistical correlation.

- The evidence may establish a causal connection without establishing what caused what.

- Examples:

- The speed at which a wind turbine rotates is correlated with the speed of the wind: the greater the one, the greater the other.

- Explanation 1: the wind makes the propeller rotate

- Explanation 2: the rotating propeller makes the wind blow.

- If you have the flu you’re more likely to die if you go to the Emergency Room.

- Explanation 1: emergency rooms, awash in germs, make people sicker.

- Explanation 2: people with the flu who go to the Emergency Room are sicker than those who don’t.

- The speed at which a wind turbine rotates is correlated with the speed of the wind: the greater the one, the greater the other.

- Examples:

Denying the Antecedent

- Denying the Antecedent is an argument of the form:

- If A, then C

- It’s false that A

- Therefore it’s false that C.

- The conditional if A then C consists of the antecedent A and the consequent C. The second premise of Denying the Antecedent denies the antecedent A.

- The argument form is invalid per logical analogy:

- If Matt Damon is over seven feet, he’s over five feet.

- Damon is not over seven feet.

- Therefore, he’s not over five feet.

- Example

- Had Saddam Hussein been responsible for the 9/11 attacks, the U.S. invasion of Iraq would have been morally justified. But Hussein was not responsible for the 9/11 attacks. Therefore, the U.S. invasion of Iraq was not justified.

- See Affirming the Consequent, Denying the Antecedent, Modus Ponens, Modus Tollens

Division

- The first form of Division is inferring that what’s collectively true of a group is thereby true of its members individually.

- Example

- People are honest on the whole. So, Matt is honest on the whole

- Example

- The second form is inferring that what’s true of something is thereby true of the things that make it up.

- Example

- Since the brain is conscious so are the neurons it comprises.

- Example

- The third form of Division is inferring that what’s collectively true of a group is collectively true of a subgroup.

- Example

- People are honest for the most part.

- Therefore, criminals are honest for the most part.

- Example

Ecological Fallacy

- The ecological fallacy is drawing a conclusion about individuals from statistics about groups (percentages, proportions, averages, rates).

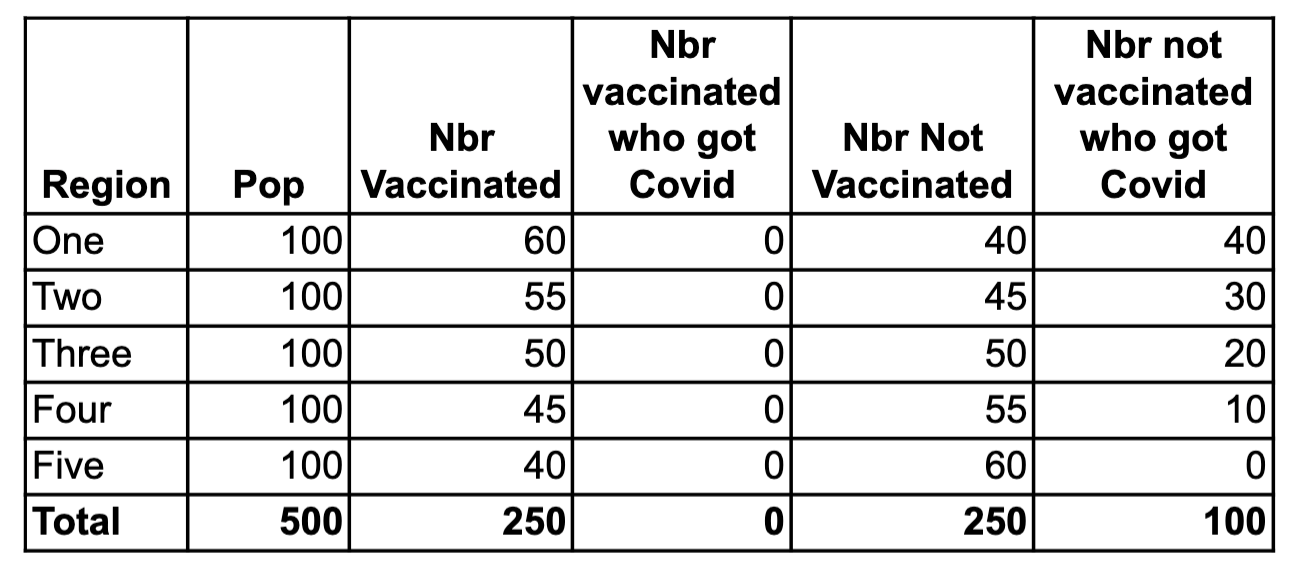

- Percentages of the vaccinated and those with Covid for a hypothetical country’s regions:

- The percentages are correlated: the larger the one, the larger the other. Indeed, the correlation coefficient is +1, a “perfect correlation.”

- Correlation[{60, 55, 50, 45, 40}, {40, 30, 20, 10, 0}] = 1

- It’s tempting to infer that getting vaccinated increases your chances of getting Covid.

- But the inference is logically invalid: the percentages are consistent with vaccinations being 100% effective:

- The percentages of the vaccinated and those with Covid are the same as above. But no one vaccinated gets Covid.

- Ecological correlations may suggest connections among individuals, but the evidence is weaker than direct correlations.

- Links

- wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecological_fallacy

- An ecological fallacy is a formal fallacy in the interpretation of statistical data that occurs when inferences about the nature of individuals are deduced from inferences about the group to which those individuals belong.

- britannica.com/science/ecological-fallacy

- Ecological fallacy is a failure in reasoning that arises when an inference is made about an individual based on aggregate data for a group.

- Ecological Inference and the Ecological Fallacy, by David Freedman

- The ecological fallacy consists in thinking that relationships observed for groups necessarily hold for individuals: if countries with more Protestants tend to have higher suicide rates, then Protestants must be more likely to commit suicide; if countries with more fat in the diet have higher rates of breast cancer, then women who eat fatty foods must be more likely to get breast cancer. These inferences may be correct, but are only weakly supported by the aggregate data.

- Aggregate data are often easier to obtain than data on individuals, and may offer valuable clues about individual behavior. Ecological inferences will therefore continue to be made. The problems of confounding and aggregation bias, however, are unlikely to be resolved in the proximate future.

- wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecological_fallacy

Equivocation

- Equivocation is an inference invalidated by a word or phrase meaning one thing in one part of the argument but something else in another.

- Example

- It’s a law of nature that nothing can go faster than light.

- Laws can be broken.

- A spaceship that goes faster than light is thus possible.

- The argument equivocates on the word law, which means law of nature in the first premise but statutory law in the second.

False Dilemma

- False Dilemma is asserting falsely that only two alternatives exist and then arguing (validly) that one is true because the other’s false.

- Example

- John Edward is either a fraud or really communicates with the dead.

- But he’s not a fraud, as anyone who knows him will tell you.

- Therefore, he really communicates with the dead

Gambler’s Fallacy

- The Gambler’s Fallacy is inferring that:

- The probability beforehand of a sequence of events H = n.

- Therefore, all the H events having happened except the last, the probability of the last H = n.

- In tossing a coin, the probability of heads is ½. In tossing two coins, the probability of two heads in a row is ½ x ½ = ¼.

- The probability of ten heads in a row is 1/1024. You just flipped nine heads. It makes sense that the probability of heads on toss 10 is 1/1024, since that would make 10 successive heads.

- But coins have no memory. The probability of heads on the tenth toss is ½.

- The ½ probability is proved using probability theory. Simplifying by tossing the coin only four times:

- For any toss, P(H) = ½

- The outcome of one coin toss doesn’t affect the probability of the next. Therefore

- P(H1&H2&H3&H4) = P(H1) x P(H2) x P(H3) x P(H4) = ½ x ½ x ½ x ½ = 1/16

- P(H1&H2&H3) = P(H1) x P(H2) x P(H3) = ½ x ½ x ½ = 1/8

- The conditional probability P(H4|(H1&H2&H3)) = P(H1&H2&H3&H4) / P(H1&H2&H3) = (1/16)/(1/8) = 1/2

Hasty Generalization

- Generalization is inferring that what is true of a sample is likely true of the population at large.

- Hasty Generalization is generalizing from a sample that’s too small.

Hypothetical Syllogism (Material Implication)

- The following argument form is surprisingly invalid:

- If A then B

- If B then C

- Therefore, if A then C

- Here’s a counterexample:

- If I win the lottery, I will give half my annual income to charity.

- If I give half my annual income to charity, I will not have enough to live on.

- Therefore, if I win the lottery, I will not have enough to live on.

- View Paradox of Hypothetical Syllogism

Intensional Fallacy

- Compare:

- Anna Argument

- Anna selected the ace of hearts.

- The ace of hearts is an ace.

- Therefore Anna selected an ace

- Probability Argument

- The probability of selecting the ace of hearts is 1/52

- The ace of hearts is an ace

- Therefore, the probability of selecting an ace is 1/52.

- Anna Argument

- The first is valid. The second is invalid, the conclusion being false.

- The difference is that the phrase selected the ace of spades in the Probability Argument occurs in what’s called an intensional context, within the scope of the word probability. Intensional contexts don’t permit deductive inference.

- The Intensional Fallacy is making a deductive inference from within an intensional context.

- Intensional contexts include believing that, thinking that, asserting that, certain that, looking for, and quotation marks. For example, suppose Matt, happily married, is looking for Sandra, a colleague at work married to someone else. Then:

- Matt is looking for Sandra.

- Sandra is a wife.

- Therefore Matt is looking for a wife.

Jumping to a Conclusion

- People sometimes make inferences from incomplete evidence. Knowing only part of the story, they jump to conclusions.

- Examples

- Believing that a semi-automatic handgun can’t fire because the magazine has been removed.

- Unaware there may be a round in the chamber.

- Believing Lee Harvey Oswald was not the lone assassin of President Kennedy after seeing Oliver Stone’s movie JFK.

- Unaware of the criticisms of movie’s arguments put forth by Gerald Posner in Closed Case and Peter Jennings in the 2004 special ABC Presents The Kennedy Assassination Beyond Conspiracy.

- Believing that Saddam Hussein played a role in the 9/11 attacks because the US invaded Iraq as part of the War on Terror. (Why else would the U.S. invade a country halfway around the globe?)

- Unaware that President Bush said in a news conference on September 16, 2003: “We’ve had no evidence that Saddam Hussein was involved with September the 11th.”

- Comment:

- In a poll by the Washington Post in August 2003, 69 percent of respondents said it was either very likely (32%) or somewhat likely (37%) that Saddam Hussein “was personally involved in the September 11 terrorist attacks.” In a 2006 Zogby Poll, 85% of troops surveyed in Iraq said the U.S. mission was mainly “to retaliate for Saddam’s role in the 9-11 attacks.

- Believing that a semi-automatic handgun can’t fire because the magazine has been removed.

Lottery Fallacy

- Here’s an obvious deductively valid form of argument:

- P

- Q

- Therefore P and Q

- Here’s another valid argument form:

- It is certain that P

- It is certain that Q

- Therefore, it is certain that P and Q.

- But the following argument form is invalid:

- It is beyond a reasonable doubt that P

- It is beyond a reasonable doubt that Q

- Therefore, it is beyond a reasonable doubt that P and Q.

- The reason is that it’s logically possible that

- For each of 10,000 convicted criminals, it’s beyond a reasonable doubt that he/she is guilty.

- It’s beyond a reasonable doubt that one of the convicted criminals is not guilty.

- See Lottery Paradox for details.

- The moral is that a deductively valid inference may lead from premises beyond a reasonable doubt to a false conclusion

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc

- Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc (“after this therefore because of this”) is inferring a causal connection merely because one thing happened after another.

- Examples

- I’ve worn an anti-elephant bracelet my entire life and never been attacked.

- In sight of tourists at Yellowstone college students turned a fake valve wheel just before an eruption of Old Faithful.

- Hours after getting a flu shot a person has a stroke.

- New York Times: Don’t Blame Flu Shots for All Ills, Officials Say

- Every year, there are 1.1 million heart attacks in the United States, 795,000 strokes and 876,000 miscarriages, and 200,000 Americans have their first seizure. Inevitably, officials say, some of these will happen within hours or days of a flu shot.

- New York Times: Don’t Blame Flu Shots for All Ills, Officials Say

- Establishing a causal connection requires more than temporal succession.

Prosecutor’s Fallacy

The Fallacy

- An example of the Prosecutor’s Fallacy:

- The suspect’s DNA profile matches that of the blood on the murder weapon.

- The probability of a match, given that it’s not suspect’s blood on the murder weapon, is 1 in a quadrillion.

- Therefore the probability it’s the suspect’s blood on the murder weapon is 0.999999999999999, a virtual certainty.

- The Prosecutor’s Fallacy is an argument of the form:

- M is the case.

- The probability of M’s being the case given that G is false is a tiny fraction n.

- Therefore the probability that G is true is a large fraction 1–n.

- In the notation of probability theory:

- M

- P(M | ~G) = n

- So, P(G) = 1 – n

- An alternative form of the fallacy:

- The probability of M’s being the case given that G is false is a tiny fraction n.

- Therefore the probability of G’s being true given that M is the case is a a large fraction 1–n.

- In symbols:

- P(M | ~G) = n

- So, P(G | M) = 1 – n

- An analogous piece of reasoning shows there’s something wrong with the Prosecutor’s argument:

- Anna won the Lottery.

- The probability of Anna’s winning the Lottery given that she didn’t cheat is 1 in 300 million.

- Therefore the probability Anna cheated is 299, 999,999 / 300,000,000, a virtual certainty

- The problem is that the argument is one-sided, a form of cherry picking. The tiny probability of winning the lottery without cheating must be weighed against the tiny probability of a person who plays the lottery cheating. Bayes Theorem (below) incorporates both probabilities.

- The Prosecutor’s Fallacy was described and named by William Thompson and Edward Schumann in their 1987 paper “Interpretation of Statistical Evidence in Criminal Trials.”

The Prosecutor’s Fallacy is half a Bayesian Inference

- The argument that the suspect’s DNA is on the murder weapon can be formulated using conditional probabilities:

- P(M | ~B) = n,

- Therefore, P(B | M) = 1 – n

- where

- M = The suspects’s DNA profile matches that of the blood on the murder weapon.

- B = The suspect’s blood is on the murder weapon

- n = 1 / 1,000,000,000,000,000

- The reformulated argument is deductively invalid.

- Let

- P(B&M) = 0.1

- P(B&~M) = 0.1

- P(M&~B) = 0.2

- P(~M&~B) = 0.6

- Then

- P(M | ~B) = 0.2 / (0.2 + 0.6) = ¼

- P(B | M) = 0.1 / (0.1 + 0.2) = ⅓

- Let

- By adding two premises, however, the reformulated argument can be made into a valid Bayesian inference.

- P(M | B) = 1

- The probability that there’s a match given the suspect’s blood on the murder weapon is 1.0

- P(B) = about 1/2, specifically (n – 1) / (n – 2)

- The probability that it’s the suspects’s blood on the murder weapon, apart from the matching profiles, is about 1/2.

- P(M | B) = 1

- The resulting Bayesian inference is valid

- P(B) = (n –1) / (n – 2)

- P(M | B) = 1

- P(M | ~B) = n

- Therefore, P(B | M) = 1 – n

- The conclusion follows by Bayes Theorem.

- P(B | M) = P(B) P(M|B) / ( P(B) P(M|B) + P(~B) P(M|~B) )

- View Bayes Theorem

- Suppose n = 1/100, for example;

- Then

- P(B | M) = P(B) P(M|B) / ( P(B) P(M|B) + P(~B) P(M|~B) )

- P(B | M) = (99/199 * 1) / ( (99/199 * 1) + (1 – 99/199) * 1/100 )

- P(B | M) = 99/100

- P(B | M) = 1 – (1/100)

- P(B | M) = 1 – n

- P(B | M) = P(B) P(M|B) / ( P(B) P(M|B) + P(~B) P(M|~B) )

- Thus the original argument that the suspect’s blood is on the murder weapon, given a match, presupposes that the probability that the suspect’s blood is on the murder weapon, apart from the DNA match, is approximately ½. But the assumption is made without evidence. If the suspect is in jail at the time, P(B) = 0.

Regression Fallacy

- Regression Toward the Mean is a statistical phenomenon where a quantity measured far above or below average is likely to be closer to the mean on a second measurement. Inferring a causal explanation for a lower measurement is the Regression Fallacy.

- View Regression Fallacy

Simpson’s Paradox

View Simpson’s Paradox

Affirming the Consequent, Denying the Antecedent,

Modus Ponens, Modus Tollens

- Denying the Antecedent and Affirming the Consequent are invalid forms of argument:

- Affirming the Consequent

- If A, then C

- C

- Therefore A

- Denying the Antecedent

- If A, then C

- It’s false that A

- Therefore it’s false that C.

- Affirming the Consequent

- In contrast, Modus Ponens and Modus Tollens are valid forms of argument:

- Modus Ponens

- If A, then C

- A

- Therefore C

- Modus Tollens

- If A then C

- It’s false that C

- Therefore it’s false that A.

- Modus Ponens

Resources

- Britannica

- Fallacy Files

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Skeptic’s Dictionary

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Wikipedia

Alphabetic List of Fallacies

- Affirming the Consequent

- Appeal to Consequences

- Argument from Ignorance

- Begging the Question

- Biased Sample / Selection Bias

- Base Rate Fallacy

- Circular Reasoning

- Composition

- Cum Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc

- Denying the Antecedent

- Division

- Ecological Fallacy

- Equivocation

- False Dilemma

- Gambler’s Fallacy

- Hasty Generalization

- Hypothetical Syllogism (Material Implication)

- Intensional Fallacy

- Jumping to a Conclusion

- Lottery Fallacy

- Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc

- Prosecutor’s Fallacy

- Regression Fallacy

- Simpson’s Paradox