Epistemology is the investigation into the nature, scope, structure, and sources of knowledge and rational belief

Introduction

- Compare the statement that Aunt Flow’s tumor is malignant to the following statements:

- It’s possible that Aunt Flow’s tumor is malignant.

- It’s likely that the tumor is malignant.

- It’s certain that the tumor is malignant

- The truth-or-falsity of the first statement depends whether Aunt Flow’s tumor is in fact malignant, that is, on the way things are, i.e. on Reality.

- The truth-or-falsity of the other three statements, by contrast, depends on the Evidence: on whether, based on the evidence (such as symptoms, scans, and biopsies), it’s possible, likely, or certain that the tumor is malignant.

- Evidence, possibility, likelihood, and certainty belong to a family of concepts that also includes:

- knowledge, rational belief, proof, reasonable doubt, established fact.

- The concepts all relate to evidence in one way or another.

- Epistemology, broadly speaking, is the study of the family of these “epistemic” concepts, as they’re called. Specifically, epistemology is the investigation into the nature, scope, structure, and sources of knowledge and rational (or justified) belief.

- The main topics:

- Nature of knowledge and rational belief

- Analysis of Knowledge

- Nature of Epistemic Justification

- Evidentialism and Reliabilism

- Internalism and Externalsim

- Epistemic Closure

- The scope of knowledge and rational belief

- Philosophic Skepticism

- The structure of knowledge and rational belief

- Foundationalism and Coherentism,

- The ultimate sources of knowledge and rational belief

- Perception, Memory, Introspection, Testimony, Reason.

- Nature of knowledge and rational belief

Philosophic Skepticism

- Philosophic Skepticism, regarding a class of propositions, is the view that there’s no rational basis for believing any of the propositions.

- For example:

- Skepticism about the External World is the view that there’s no rational basis for believing there are physical objects — tables, trees, cars, houses, and the myriad other things that occupy space and time

- Skepticism about Other Minds is the view that there’s no rational basis for believing that other people have thoughts, sensations, feelings, and emotions.

- Alternative formulations of Philosophic Skepticism regarding a proposition P:

- No one is justified in believing P

- It’s irrational to believe P

- No one knows that P is true

- No on knows whether P is true

- One ought to suspend judgment regarding P

- It’s an open question whether P.

- A curious feature of philosophic skepticism is that proponents continue to believe the things they say are irrational to believe. Normally, if you’re skeptical of a claim, you don’t believe it. If you believe there’s no basis for believing that the 2020 presidential election was stolen, for example, you don’t believe it was stolen. But a philosophic skeptic who believes, for example, that there are no grounds for believing that physical objects exist still believes he has arms and legs, hands and feet. Indeed, people, including skeptics, can’t help believing that there are physical objects. As David Hume put it, “nature is always too strong for principle.”

Arguments for Philosophic Skepticism

- There are two basic ways to argue that it’s irrational to believe a proposition P.

- One is to argue that it’s irrational to believe P because (a) there’s a logically possible scenario S where P is false and (b) there’s no more basis for believing P than for believing S.

- The other is to argue that it’s irrational to believe P because the arguments set forth supporting P are defective.

- Thus a skeptic can argue that’s it’s irrational to believe that other people experience pain because

- (1) there is no more basis for believing that other people are conscious beings than for believing they are “philosophic zombies”

- and because

- (2) the arguments that other people experience pain fail because they beg the question.

Skeptical Hypothesis Argument

- The first way of arguing that it’s irrational to believe a proposition P is by arguing that

- (a) there’s a logically possible “skeptical hypothesis” S that P is false and

- (b) there’s no more basis for believing P than for believing S.

- The Skeptical Hypothesis Argument was made famous by Descartes who, in his quest to find indubitable truths, conjured up an “evil genius of the utmost power and cunning has employed all his energies in order to deceive me.” Descartes was able to find one indubitable truth: that he was thinking. From which he inferred another: that he existed. From there, however, things went downhill. It seems that Descartes was no match for his own Evil Genius.

- Form of the Argument:

- Abbreviations

- E = Evidence

- C = Common-Sense Hypothesis

- S = Skeptical Hypothesis

- Argument

- 1. C and S are competing hypotheses set forth to explain E.

- 1. There is no rational basis for believing that either C or S is more likely than the other.

- 2. If there’s no rational basis for believing that either of two competing hypotheses is more likely than the other, it’s not rational to believe either.

- Therefore, it’s not rational to believe C.

- Abbreviations

- A Valid instance of the Argument:

- You spot someone in a bookstore whom you take to be an acquaintance from work. You then see him steal a book. Chatting with him next day at work you learn that he was indeed at the bookstore. But you also learn that he has an indistinguishable identical twin; and the twin was in the bookstore too. At this point you have no basis for believing your coworker stole the book, since it’s equally likely, based on what you witnessed, that it was the identical twin you saw steal the book.

- E, C and S are thus:

- E = You saw someone who looks exactly like your coworker steal a book.

- C = The coworker stole a book

- S = The coworker’s identical twin stole a book

- Brain-in-a-Vat Argument for Skepticism about the External World

- In the brain-in-a-vat scenario a person undergoes an operation in which their brain is removed and stored in a vat of nutrients that keeps it alive. The nerve endings of the brain are connected to a supercomputer that sends electrical impulses stimulating the brain so that their mental experiences are indistinguishable from those they would have were they a normal human being.

- The Argument

- I currently have the experience of seeing and sensing my hand.

- Consider two hypotheses:

- I have a normal human body by which I see and sense my hand.

- I’m a brain-in-vat and, with no hands, I don’t see and sense my hand

- Yet I still have the experience of seeing and sensing my hand because the supercomputer is transmitting electrical impulses to my brain that cause the experience.

- I have no basis for believing that either of these hypotheses is more likely than the other.

- That’s because the only relevant evidence is my immediate experience, which is the same in both scenarios.

- If there’s no basis for believing that one of two competing hypotheses is more likely than the other, it’s not rational to believe either.

- Epicurus: “if one accepts one explanation and rejects another that is equally in agreement with the evidence, it is clear that he is altogether rejecting science and taking refuge in myth” (Letters, Principal Doctrines, and Vatican Sayings).

- Therefore, it’s not rational to believe I see and sense my hand.

- E, C, and S are thus:

- E = I have the experience of seeing and sensing my hand.

- C = I have a normal human body by which I see and sense my hand.

- S = I’m a brain-in-vat and, with no hands, I don’t see and sense my hand

- Philosophic Zombie Argument for Skepticism about Other Minds

- Philosophic zombies are hypothetical beings that resemble human beings in all physical respects but are completely devoid of conscious experience and awareness. They converse, they laugh, they cry. But there are no thoughts, sensations, or feelings behind their behavior.

- The Argument

- You witness Sam writhing on the floor, groaning, and cursing like a sailor.

- Consider two hypotheses:

- Sam, a normal human being, is experiencing pain

- Sam, a philosophic zombie, is not experiencing pain

- You have no basis for believing that either of these hypotheses is more likely than the other.

- That’s because the only relevant evidence is Sam’s behavior, which is the same in both scenarios.

- If there’s no basis for believing that one of two competing hypotheses is more likely than the other, it’s not rational to believe either.

- For example, if it’s equally likely that a plane crash was caused by pilot error as it was by mechanical failure, it’s irrational to believe either.

- Therefore, it’s not rational to believe that Sam is in pain.

- E, C, and S are thus:

- E = Sam is writhing on the floor, groaning, and cursing like a sailor

- C = Sam, a normal human being, is experiencing pain

- S = Sam, a philosophic zombie, is not experiencing pain

Defective-Evidence Argument

- The second way of arguing that it’s irrational to believe a proposition P is to argue that the arguments set forth supporting P are defective. I shall consider arguments that, according to the skeptic, beg the question.

- An argument that for a proposition P begs the question if one of the premises

- presupposes that P is true

- is not established by further premises.

- Consider, for example, the following argument:

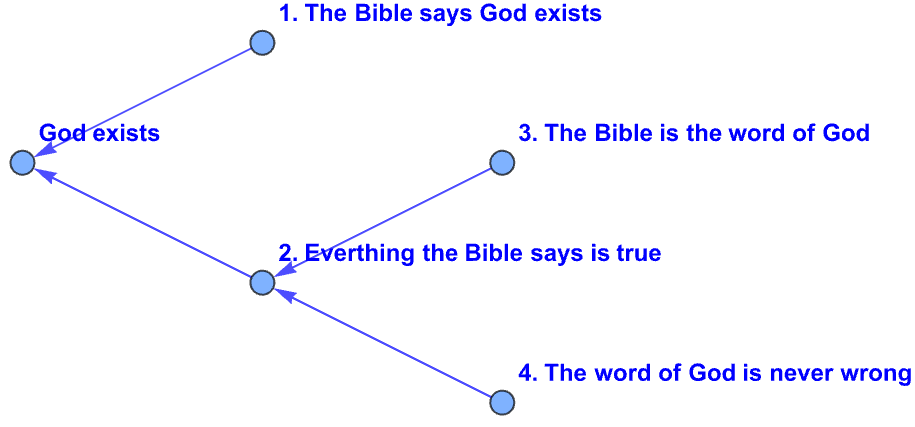

- That God exists is established by fact that (1) the Bible says God exists and (2) everything the Bible says is true, which in turn is established by the fact that (3) the Bible is the word of God and (4) the word of God is never wrong.

- The argument can be depicted as a tree, where the arrow means “is established by.”

-

- The argument begs the question because premise (3)

- presupposes what was to be proved, that God exists

- is not supported by further premises.

- Defective-Evidence Argument for Skepticism about the External World

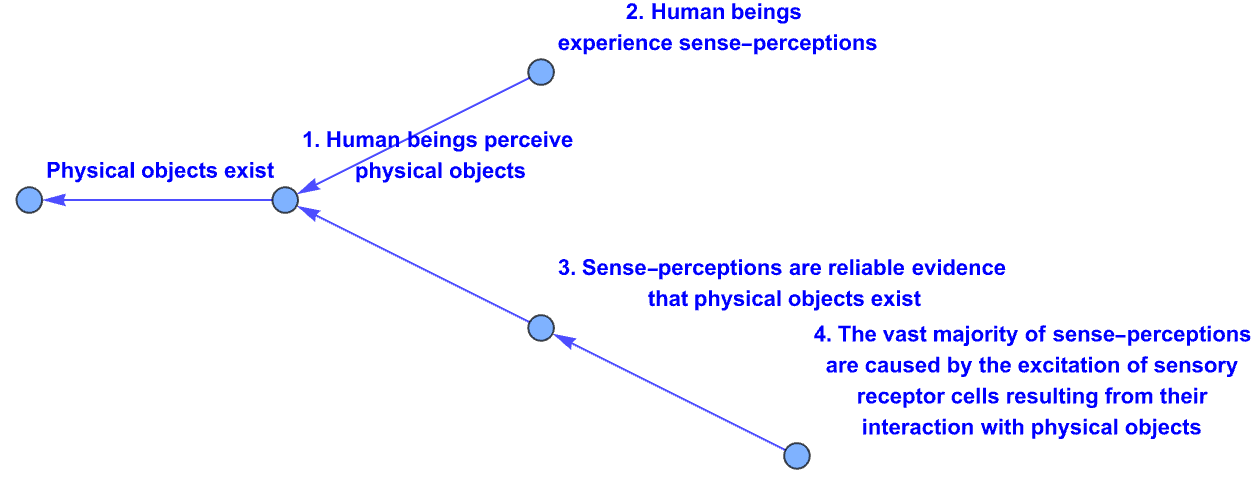

- Consider the argument that physical objects exist:

- That physical objects exist is established by the fact that (1) human beings perceive physical objects, which in turn is established by the fact that (2) human beings experience sense-perceptions and (3) sense-perceptions are reliable evidence that physical objects exist, which in turn is established by the fact that (4) the vast majority of sense-perceptions are caused by the excitation of sensory receptor cells resulting from their interaction with physical objects.

- The argument can be depicted as a tree, where the arrow means “is established by.”

- The argument begs the question because premise (4) presupposes that physical objects exist and is not supported by further premises.

- Thus, the argument fails to establish that physical objects exist.

- Comment

- Premise (1) presupposes that physical objects exist but does not beg the question because it is supported by further premises (2) and (3).

- Consider the argument that physical objects exist:

- Defective-Evidence Argument for Skepticism about Other Minds

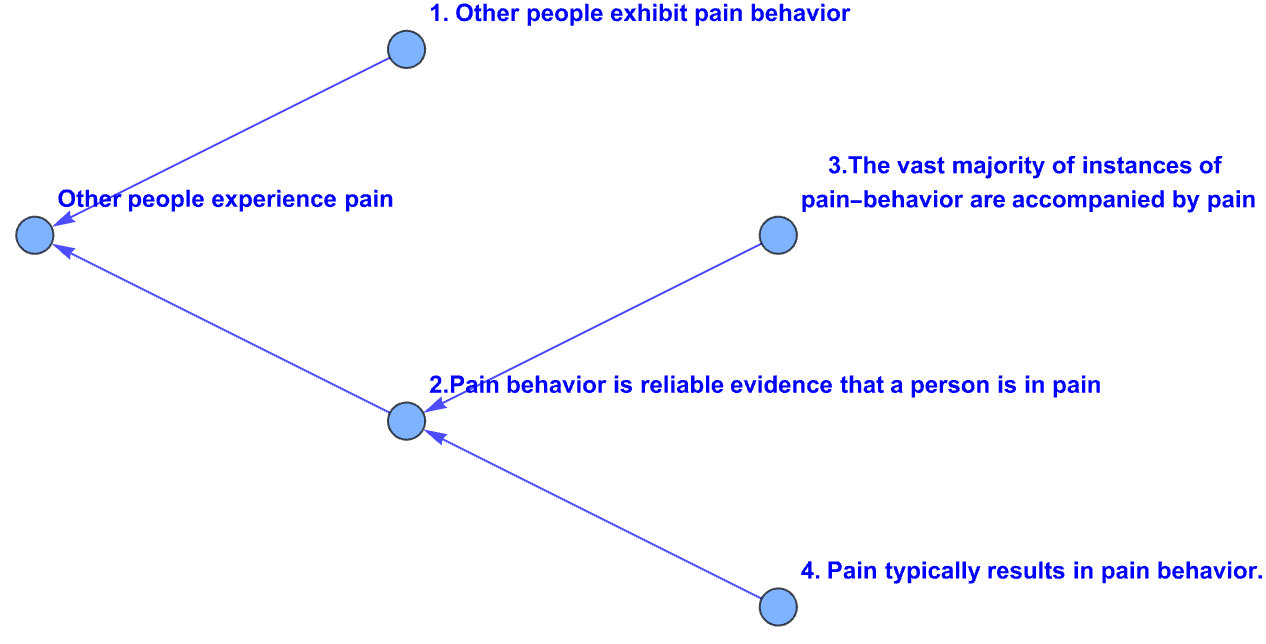

- Consider the argument that other people experience pain:

- That other people experience pain is established by that that (1) other people exhibit pain behavior and (2) pain behavior is reliable evidence that a person is in pain, which in turn is established by the fact that (3) the vast majority of instances of pain-behavior are accompanied by pain and (4) the experience of pain typically results in pain behavior.

- The argument can be depicted as a tree, where the arrow means “is established by.”

-

- The argument begs the question because premise (3) presupposes that other people experience pain and is not supported by further premises.

- Thus, the argument fails to establish that other people experience pain.

- Consider the argument that other people experience pain:

Replies to Philosophic Skepticism

Common Sense

- Philosophers have different starting points, e.g. sense-perception, a priori principles, indubitable truths. Another starting point is common sense. Philosophers such as Thomas Reid, G.E. Moore, and Roderick Chisholm begin by assuming those things that are true as a matter of common sense, for example:

- that there are physical objects that exist in space and time and interact causally

- that human beings have physical bodies, experience mental phenomena, and perceive physical objects.

- These philosophers reply to skeptical arguments by appealing to what most everyone regards as obvious.

- Here’s a straightforward argument against skepticism about the external world:

- It’s beyond a reasonable doubt that I have a head (among many other things that are beyond a reasonable doubt). Indeed, I know I have a head (among many other things I know).

- Therefore, any (skeptical) argument that implies that there’s a reasonable doubt that I have a head or that I don’t know I have a head is wrong.

- Thus, for example, the brain-in-a-vat argument is wrong.

- Here’s a reductio ad absurdum argument against skepticism about other minds:

- Assume that, per the philosophic skeptic, it’s irrational to believe that other human beings, like oneself, are conscious beings (rather than philosophic zombies).

- Suppose a defendant D is on trial for murder.

- Then there’s a reasonable doubt that D is a conscious being.

- If there’s a reasonable doubt that D is a conscious being, then there’s a reasonable doubt that D had criminal intent (mens rea) in committing the alleged murder.

- If there’s a reasonable doubt that D had criminal intent, then there’s a reasonable doubt he’s guilty of murder.

- Therefore, it’s not beyond a reasonable doubt that D is guilty of murder.

- Thus, if philosophic skepticism about other minds is true, it’s not beyond a reasonable doubt that anyone is guilty of murder.

- These arguments make a strong case that there’s something wrong the skeptic’s arguments. But they don’t explain how those argument go wrong. They don’t explain why, for example, given a person’s immediate experience, it’s more rational to believe they’re a normal human being with a head than to believe they’re a headless brain-in-vat.

Inability to Believe Otherwise or Suspend Judgment

- Is it rational for me to believe that there’s a world of physical objects beyond my sensations? What are the alternatives? I could believe that my sensations are caused by a Cartesian demon. I could believe that I’m a brain-in-vat. Or I could simply suspend judgment on the matter. But of course I can’t do any of these things. I can’t refrain from believing there’s an external world.

- On which basis Thomas Reid argues:

- “Methinks, therefore, it were better to make a virtue of necessity; and, since we cannot get rid of the vulgar notion and belief of an external world, to reconcile our reason to it as well as we can; for, if Reason should stomach and fret ever so much at this yoke, she cannot throw it off; if she will not be the servant of Common Sense, she must be her slave.

- All reasoning must be from first principles; and for first principles no other reason can be given but this, that, by the constitution of our nature, we are under a necessity of assenting to them.“

- An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense, 1764, Chapter V: Of Touch, Section VII: Of the existence of a material world

Abduction / Simplicity

- In Problems of Philosophy Bertrand Russell argues that it is rational to believe that there is a world of physical objects because the hypothesis of an external world is the simplest explanation of our sensations.

- “There is no logical impossibility in the supposition that the whole of life is a dream, in which we ourselves create all the objects that come before us. But although this is not logically impossible, there is no reason whatever to suppose that it is true; and it is, in fact, a less simple hypothesis, viewed as a means of accounting for the facts of our own life, than the common-sense hypothesis that there really are objects independent of us, whose action on us causes our sensations.

- The way in which simplicity comes in from supposing that there really are physical objects is easily seen. If the cat appears at one moment in one part of the room, and at another in another part, it is natural to suppose that it has moved from the one to the other, passing over a series of intermediate positions.”

Analysis of Knowledge

- In the dialogue Theaetetus, Socrates (speaking for Plato) raises the question whether knowledge is true belief, that is, whether knowing that something is the case is the same as believing correctly that it is the case.

- Plato’s insightful and correct answer was no. He provides an example, here paraphrased and embellished:

- Suppose a jury comes to believe that the defendant is guilty based only on rumor and hearsay. Suppose also that the defendant happens to be guilty. The jury thus correctly believes that the defendant is guilty. Yet they can’t be said to know that fact since, given that their belief was based on mere rumor and hearsay, they could have been mistaken.

- Thus knowledge is more than mere true belief. But what more?

- The contemporary debate about the nature of propositional knowledge begins with the idea of knowledge as justified true belief:

- Person S knows that P is logically equivalent to:

- P is true,

- S believes that P, and

- S is justified in believing that P

- View Logical Equivalence

- Person S knows that P is logically equivalent to:

- The JTB analysis makes sense. The jurors in Socrates’ example don’t know the defendant is guilty because rumor and hearsay are insufficient justification for their belief.

- But the JTB analysis is wrong.

- In 1963 Edmund Gettier published a three-page paper1 setting forth two counterexamples to the JTB analysis, which led to the publication of hundreds of papers trying to repair the analysis. It also led to a variety of different kinds of counterexamples.

- The idea of Gettier counterexamples is that it’s logically possible that

- (1) a person S is justified in believing proposition P

- (2) P is true

- (3) But it’s a fluke (in some sense) that S’s belief that P is correct

- (4) Therefore, S doesn’t know that P.

- A typical Gettier counterexample:

- I spot someone in a bookstore I take to be Tom, an acquaintance from work. Then I see him steal a book. I’m thus justified in believing that Tom stole a book. I’m unaware, however, that Tom has an indistinguishable identical twin; and it’s Tom’s twin I saw steal a book. The kicker is that Tom was in the bookstore at the same time and he too stole a book.

- Therefore:

- It’s true that Tom stole a book, though I didn’t see him do it.

- I believe Tom stole a book.

- I’m justified in believing that Tom stole a book, since the person I saw looked exactly like Tom.

- But I don’t know that Tom stole a book, since my belief is true only by chance.

- Numerous attempts to repair the JTB analysis have failed.

- See plato.stanford.edu/entries/knowledge-analysis for details.

- For example, adding either of the following as a fourth condition doesn’t work.

- S’s belief that P is not inferred from any falsehood.

- Were P false S would not believe P.

- And replacing the third condition (“S is justified in believing that P” ) with either of these also fails.

- S’s belief that P was produced by a reliable cognitive process.

- S’s belief that P is caused by the fact that P.

- But there’s a simple fix that seems to work: replace the third condition with “it is certain that P, based on S’s evidence.”2 That is, a person S knows that P if and only if:

- P is true,

- S believes that P, and

- It is certain that P, based on S’s evidence.

- Thus, I don’t know that Tom stole a book because, based on the evidence I have, it’s not certain that he stole a book. It’s not certain because it’s possible, based on my evidence, that Tom didn’t steal a book, since I would have had the same evidence had Tom not stolen a book. Thus, it’s not certain, based on my evidence, that Tom stole a book.

- The argument can be spelled out as follows:

- Let P be the proposition that Tom stole a book.

- It’s possible that P is false, based on my evidence.

- That is, it’s possible that Tom didn’t steal a book, based on my evidence, because I would have had the same evidence had Tom not stolen a book.

- If it’s possible that P is false, based on my evidence, then it’s not certain that P, based on my evidence.

- If it’s not certain that P, based on my evidence, then I don’t know that P.

- Because condition (3), that “it is certain that P, based on the evidence,” is not satisfied.

- Therefore I don’t know that P.

- That is, I don’t know that Tom stole a book.

- The argument can be spelled out as follows:

- Knowledge, it seems, requires the highest standard of evidence: certainty. Nothing less will do, whether it’s beyond a reasonable doubt, preponderance of evidence, or justified belief.

Detailed Contents

- Analysis of Knowledge

- Knowledge as justified true belief versus knowledge as certain belief.

- Arguments

- An argument is an instance of reasoning, from premises to a conclusion.

- Conspiracy Theories

- A conspiracy theory explains events by invoking a secret plot by a group of conspirators.

- Ockham’s Razor provides an a priori reason for rejecting conspiracy theories, since the straightforward explanation of events is simpler.

- Determining What’s True

- Pitfalls of Reasoning

- Knowability a Priori and Necessary Truth

- Fact Checking

- Forecasting

- Rational Belief / Epistemic Justification

- Degrees

- Sources

- Introspection

- Memory

- Perception

- Testimony

- Reason

- Structure

- Theories

- Skepticism

- Practical vs Philosophic Skepticism

- Philosophic Skepticism

- Practical Skepticism

Footnotes

- Gettier, Edmund L., 1963, “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?”, Analysis, 23(6): 121–123 ↩︎

- In “Why I Know so Much More than You Do” American Philosophical Quarterly (Oct, 1967), William W Rozeboom wrote that “”knowing p analytically requires …that there be some sense in which, considering the circumstances, it is completely certain that p.” ↩︎